The numbers that show the economy might be doing better than you think

The latest growth figures paint a picture of an economy that is struggling along at best. But dig beneath the headline numbers and there are reasons for optimism, says Chris Blackhurst

Rachel Reeves’s critics were quick to pounce this week after the Office for National Statistics reported that the UK economy had grown by 0.1 per cent in the final three months of last year, and GDP per head had also fallen by the same amount.

Shadow chancellor Mel Stride said it showed that “Labour’s choices have weakened our economy”. For the Lib Dems, deputy leader Daisy Cooper accused the government of having “killed off” an economic recovery with two “anti-growth Budgets”.

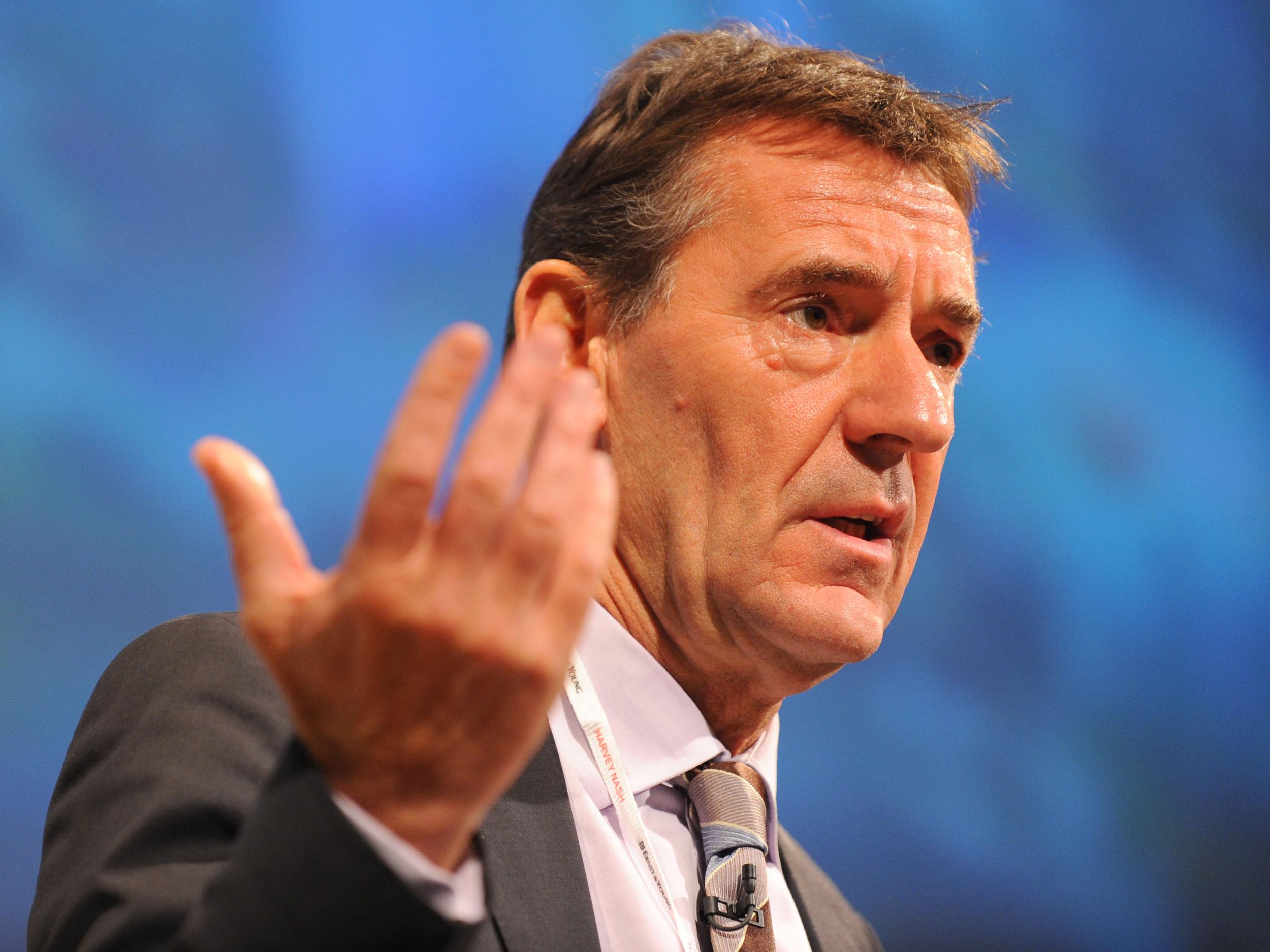

But economist Jim O’Neill, a crossbench peer and former Conservative Treasury minister, was not so negative. Speaking on Radio 4’s Today programme, he said the fourth-quarter growth figures were not that important, while some data for January, including for retail sales, was “surprisingly stronger than people expected”.

The 2025 annual growth figure of 1.3 per cent, O’Neill said, is “quite a bit higher than consensus expectations at the start”. He added: “Of course it is nowhere near strong enough, or good enough, to be impacting normal people. But it’s actually better.”

O’Neill was upbeat: “The underlying productivity of the economy is showing tentative signs of finally starting to improve,” he declared. Asked if his glass was half full or half empty, he replied: “It’s more half full than it’s been for some time.”

So, who is right, Reeves’s opponents or O’Neill? The statistics do require some unpicking.

It’s true that British Retail Consortium figures reveal that retail sales increased by 2.7 per cent in January, up from 1.2 per cent in December, and above the 2025 average of 2.3 per cent. O’Neill is correct, as well, when he says that the annual GDP figure of 1.3 per cent is higher than the consensus back in January 2025, which was 1.2 per cent – although his “quite a bit” might be stretching it.

He’s right, too, that UK productivity – the bete noir of successive recent governments – grew more in the past year than in the previous seven years combined. The latest official Labour Force Survey discloses a 1.1 per cent rise in productivity – how much the economy produces per number of hours worked.

Greg Thwaites, research director at the Resolution Foundation think tank, has produced a study based on a different measure – payroll data, or the number of employees receiving a payslip – which shows that productivity grew by 3.1 per cent over those four quarters. “That’s not a rounding difference,” said Thwaites. “It’s the gap between ‘solid’ and the best non-pandemic year since before the financial crisis.”

Thwaites also concluded that productivity is “genuinely picking up”. Cue the popping of champagne corks in Nos 10 and 11 Downing Street.

Not so fast. Productivity may be rising, but that’s partly because there is something of a clearout taking place. Interest rates were more or less zero for over a decade, energy was cheap, and the minimum wage was low. That meant the economy was packed with zombie businesses – ones that were doing very little, merely chugging along, surviving rather than thriving.

Now, though, interest rates are up, energy is more expensive, and the minimum wage has risen. Those neither-dead-nor-alive firms have struggled to cope, so they’ve laid people off or closed altogether. Currently, unemployment is at 5.1 per cent, the highest it’s been in a decade outside the pandemic. Output is rising slowly, but thanks to there being fewer workers, the number of hours worked to produce it is dropping fast, which is how you arrive at that 3.1 per cent. In short, those in work are having to work harder. “The productivity gains are real, but they’re coming partly from fewer people working, not just from more output being produced,” said Thwaites.

So, not quite as rosy after all. Crucially, too, what should happen in a healthy economy is that those businesses that vanish are replaced by new, more productive ones – “creative destruction”, as the economist Joseph Schumpeter termed it. But this churn is not happening – or at least, the new firms are not hiring those unemployed workers. Why? Because there is a mismatch between the businesses and jobs that are disappearing and the newcomers. Bar staff who are made redundant, for instance, cannot simply walk into an AI start-up.

Those stronger retail sales figures may also not be quite what they appear. “Many shoppers held off Christmas spending and waited for the January sales,” said Helen Dickinson, chief executive of the British Retail Consortium. “A drab December gave way to a brighter January.”

Yes, but that is still brighter. They did decide to spend.

The S&P Purchasing Managers’ Index for services and manufacturing is another positive pointer. It’s reporting the fastest lift in activity since August 2024. Other indicators: Nationwide and Rightmove claim house prices are moving upwards again; and research company GfK claims consumer confidence has risen for the second consecutive month, again post-Budget.

Reeves was not as hard on business as predicted. Companies and individuals are committing money and investing. But only slowly, and nervously. Those sales figures, for example, mask the fact that among the biggest sellers are gold and silver jewellery items – a sanctuary in times of worry.

In one vital area, too, there is considerable gloom. Housebuilding is an economic galvaniser. There, the news is gloomy – planning permission is slow to obtain, and very little is being built. The government has said it will speed up the planning process, but there is precious sign of that occurring. At the same time, inflation in materials and labour (exacerbated by a shortage of skilled builders), alongside sluggish demand, has heaped pressure on the sector, so much so that companies are talking in terms of a “viability crisis”.

O’Neill’s glass may be more half full than it’s been for a while. Whether it stays that way is far from certain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks