Aung San Suu Kyi has spent 20 years imprisoned – will she live to see freedom?

After two decades of confinement, Myanmar’s most famous political prisoner is in failing health and faces her final years behind bars. Whatever her failures in office, allowing Suu Kyi to die in jail would be a grave injustice, says Benedict Rogers

Myanmar’s pro-democracy leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, turned 80 last year, and last Friday reached a cumulative total of 20 years in detention. The question facing her, the illegal military junta that now rules her country, and the international community is stark: will she die in jail?

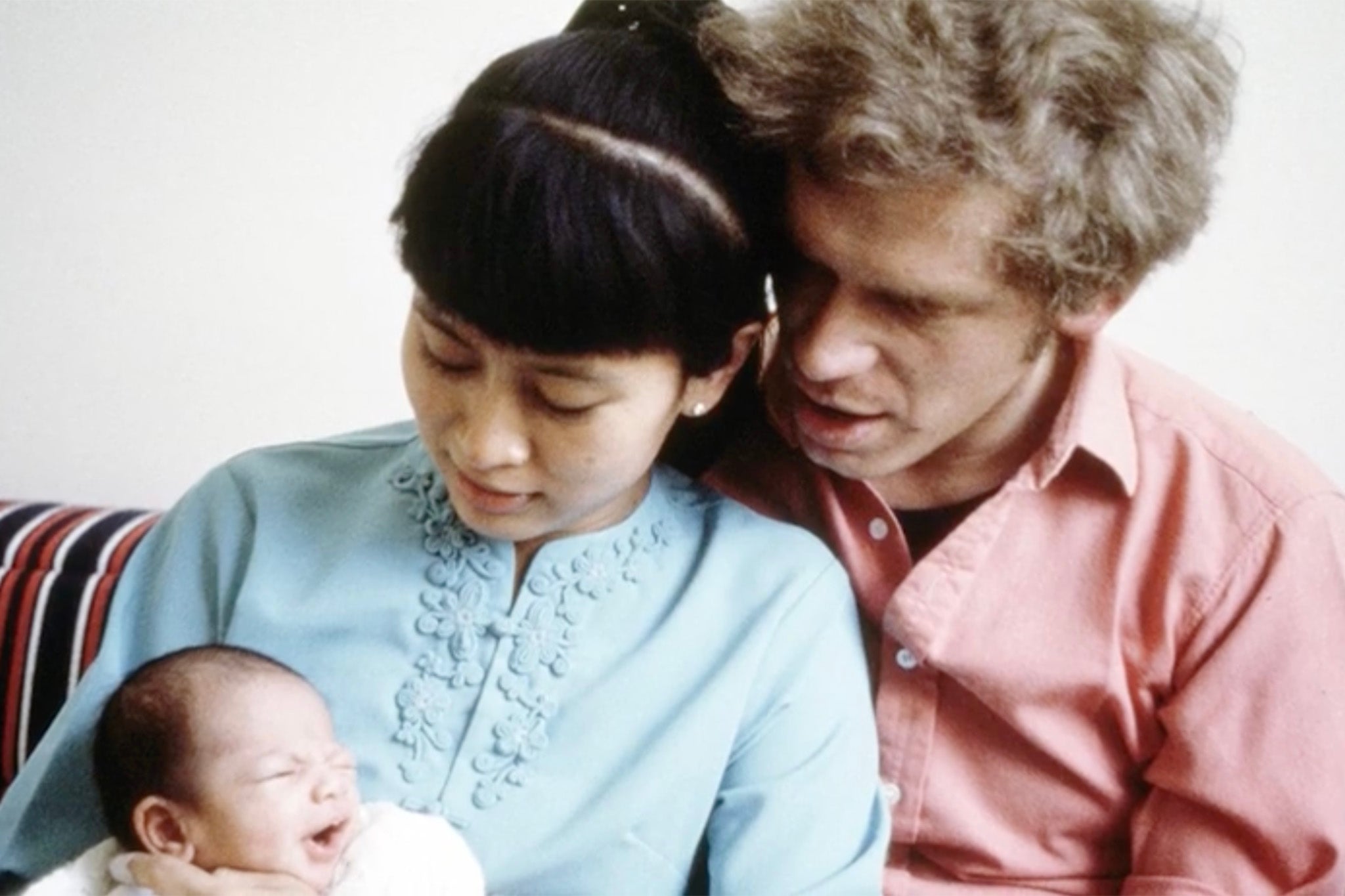

Suu Kyi captured the hearts of Myanmar’s pro-democracy activists during protests that swept the country in 1988. She had returned home to Yangon from her comfortable life as the wife of an Oxford academic to nurse her dying mother.

But when protesters against the then dictatorship of General Ne Win learned that the daughter of modern Myanmar’s founding father, General Aung San, was back in the country, they appealed to her for support.

Her father had led the country’s struggle against British colonial rule, but was assassinated in 1947, six months before independence, when she was just two years old. Although she barely knew him, she has carried his name and legacy throughout her life.

When she returned to look after her elderly mother 38 years ago, Suu Kyi could not have known she would spend over half the ensuing years in detention, separated from her two sons, Kim and Alexander.

Perhaps she sensed what lay ahead, however, because before marrying Michael Aris, a scholar of the Himalayas, she wrote to him from Bhutan in 1972, saying: “I ask only one thing. That should my people need me, you would help me do my duty by them. Would you mind very much should such a situation ever arise? … Sometimes I am beset by fears that circumstances and national considerations might tear us apart.”

Suu Kyi’s 20 years in detention have not been a single sentence, but a series of sentences, punctuated by brief periods of release. She was first detained and placed under house arrest in her mother’s home on University Avenue in Yangon in 1989. She spent six years there, cut off from her people but surrounded by books, her piano and her radio, until her release in 1995.

Even then, her persecution did not end. Her husband died from cancer in 1999, shortly after being refused a visa to visit as he was dying, and she was unable to attend his funeral. For five years, she resumed her political activities, travelling the country and directly challenging the regime, before being re-arrested in 2000 and held for another two years. In 2003, just a year after her release, she was detained for a third time, this time for seven years.

In 2010, after the military organised a sham election to legitimise its rule, Suu Kyi was released once more. A year later, the then military-backed president, former General Thein Sein, invited her for talks. What followed appeared to mark a new era.

Political prisoners were freed, space for civil society and the media opened up, ceasefire talks with ethnic armed resistance groups began, and Suu Kyi and her colleagues from the National League for Democracy won seats in Parliament in by-elections in 2012. She travelled the world, heralded as Myanmar’s Nelson Mandela. In 2015, she won an overwhelming general election victory and entered a power-sharing arrangement with the military.

Although the constitution had been rewritten specifically to prevent her from becoming president because of her marriage to a foreigner, she assumed the role of state counsellor – the de facto premier – while a handpicked president fulfilled largely ceremonial duties.

During her five years as head of government, Suu Kyi never wielded complete power. Under the military-drafted constitution, the armed forces controlled three key ministries – home affairs, border affairs and defence – and held a quarter of all parliamentary seats, reserved for serving officers. She was constantly walking a tightrope, governing within a compromise imposed by an army that had ruled Myanmar for more than half a century.

Her ambition was to gradually expand democracy and curtail the military’s influence. That hope was steadily undermined by the armed forces’ continued grave human rights abuses. By the end of her term, her international reputation lay in tatters, overshadowed by the genocide of the predominantly Muslim Rohingya people and by war crimes and crimes against humanity committed against the predominantly Christian Kachin, Karen and other ethnic groups, all carried out on her watch.

Her record in office remains contested. Critics point to comments she made that appeared dismissive of the military’s crimes and, at times, seemed to inflame division – most notably her denial of the Rohingya genocide. Supporters argue that she pursued peace behind the scenes and highlight her decision to establish an independent inquiry, led by former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan, to make recommendations on the Rohingya’s plight.

The Annan Commission’s report – which sketched the beginnings of a way forward – was fatally derailed by attacks on military outposts by Rohingya militants on the very day it was released. What followed was a pre-planned genocidal campaign by the military against the Rohingya.

Her decision to travel to The Hague to defend Myanmar at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against genocide charges brought by The Gambia was among her most consequential errors. For me, it was a Rubicon. I had tried to understand, defend, or at least explain her. After that, I could no longer do so.

There is a tragic irony in the timing. This week, as we mark her two decades in detention, the ICJ’s proceedings have reopened, and the case against Myanmar’s military for genocide begins in earnest. One cannot help but wonder what she makes of it from her prison cell – and whether she would still stand before the court to defend Myanmar’s army today.

Yet, whatever her failures in office, Suu Kyi won re-election in November 2020. Had democracy been upheld, she should now be completing her second term in government and, given her age, preparing to pass the baton to a new generation. Instead, following her arrest after the coup on 1 February 2021, she sits in prison, serving a 33-year sentence on wholly fabricated charges, later commuted to 27 years – longer than the two decades she had already spent in detention.

This time, there is no house arrest. She is held in jail, with little or no access to her books, her beloved piano, her lawyer or doctor, and she is in failing health.

Nor is she alone. Almost the entire democratic opposition in Myanmar is imprisoned, exiled, or has taken up arms against the junta.

The elections taking place this month are a grotesque charade amid mass incarceration, the banning of democratic parties, and the military’s relentless atrocities, including the bombing of schools, clinics and religious sanctuaries.

Suu Kyi is not perfect. For years, she was elevated as a saint – a beautiful, detained pro-democracy icon with orchids in her hair. She was then just as swiftly cast down, stripped of honours and denounced as an accomplice to genocide. The truth, inevitably, is more complicated.

Like any human being, she has virtues and flaws. She made compromises many find unpalatable, misjudgements some consider unforgivable, and decisions that continue to divide opinion. She failed to place the aspirations of Myanmar’s ethnic and religious minorities at the heart of her political vision. She displayed prejudices that few expected, and said things that shocked even her supporters.

Having met her several times – in Yangon, Naypyidaw and London – I can attest to her charm and courage, but also to her steel and intransigence. These qualities together explain both her achievements and her failings, and have accompanied her through four decades of struggle for freedom.

Whatever one thinks of her character or record, her imprisonment today is a profound injustice. As Myanmar’s democratically elected leader, she should be held to account before parliament and by international institutions, and required to answer for her decisions – as any elected leader must. Instead, she languishes in a bleak prison, cut off from the world.

That is a grotesque climax to an almost Shakespearean tragedy – and one the international community must not allow to stand.

Given her family ties to Britain, and Britain’s colonial history in Myanmar, the UK has a particular responsibility to lead efforts to secure her release – and that of the more than 22,000 political prisoners who remain in Myanmar’s jails – and to hold the perpetrators of this repression to account.

If she remains imprisoned much longer, she will die there. A brave yet deeply flawed Nobel Peace Prize laureate will be laid to rest beneath a disputed legacy, amid a continuing travesty of injustice for her and for a country still suffering under an illegitimate and brutal regime.

Benedict Rogers is a human rights activist and writer, senior director at Fortify Rights, and author of three books on Myanmar, including ‘Burma: A Nation at the Crossroads’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks