Isis did not disappear – and its new generation has a terrifying warning

As a link between the terror organisation and the Bondi Beach gunmen is investigated, Peter Neumann, author of ‘Isis: the Inside Story’, explains how it has evolved as a group, and why we should be worried by the chilling call to arms made just months ago

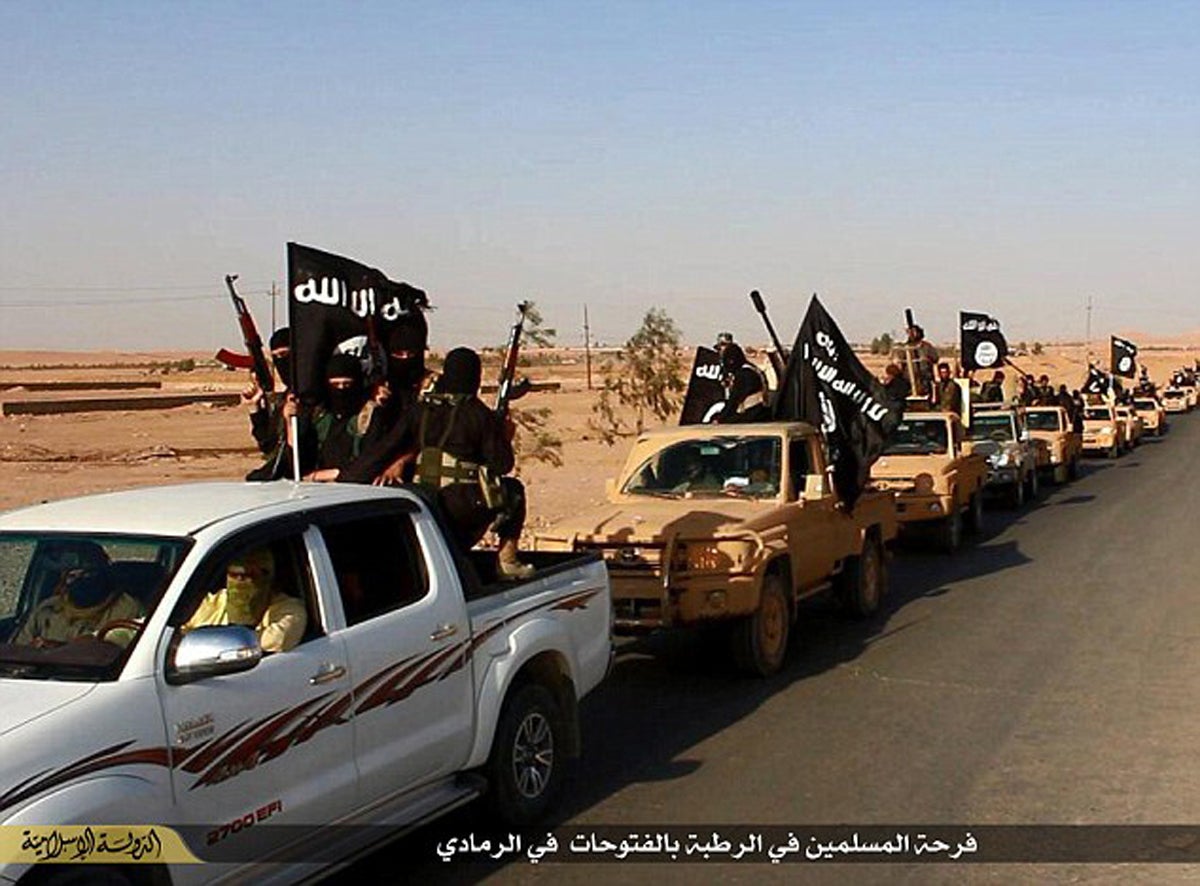

Isis is not what it used to be. At its peak a decade ago, the group governed a territory in Iraq and Syria that was roughly the size of Great Britain, with a population of nearly 10 million people. It declared so-called provinces across three continents and projected an image of unstoppable momentum. That version of Isis no longer exists.

Its self-declared “caliphate” was comprehensively defeated by decisive international action led by the United States and its allies. By 2019, Isis controlled little more than a handful of villages along the Syrian-Iraqi border. With the collapse of territorial control came the end of its centrally directed global terror campaign, which had reached Europe and Britain by the mid-2010s with devastating attacks in Paris, Brussels, Manchester, London, Berlin, Stockholm, Barcelona, and other European cities.

But while Isis was beaten, it did not disappear. It has now emerged that the alleged father-and-son gunmen who killed 15 people and injured 40 more in the mass shooting at Bondi Beach may have been inspired by the Isis terrorist organisation.

Sajid Akram, 50 and Naveed Akram, 24, allegedly stood on an overpass bridge near to the event and shouted “Allahu Akbar” as they carried out the massacre, and New South Wales police force commissioner Mal Lanyon said a car registered to Naveed Akram contained IEDs and Isis flags.

“It would appear that this was motivated by Islamic State ideology,” Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese told ABC Sydney.

A spokesperson for Australia’s immigration bureau has also confirmed that the alleged gunmen left Australia for the Philippines six weeks ago and returned on a flight to Sydney on 28 November. The pair listed Davao as their destination upon their arrival in the Philippines. While the reason for their trip is still being investigated, Davao, a sprawling city on the eastern coast of Mindanao – the largest of the southern islands – lies within a region where Islamist militants have historically operated in poorer central and southwestern areas.

Isis and similar groups have found it hard to recruit foreign fighters and operate from a base to direct operations of the kind it masterminded a decade ago. Some fighters remained in the Syria-Iraq region and went underground. Others relocated to fragile states and conflict zones elsewhere. For several years, Africa appeared to be the new epicentre of jihadist violence, with insurgencies and terrorist campaigns flaring up from the Sahel to Mozambique – conflicts that continue to this day.

Meanwhile, Europe experienced something close to a lull in jihadist activity. By the early 2020s, terrorist attacks had fallen to a level that prompted security and intelligence services to shift their focus to other threats. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, political and strategic attention was almost entirely consumed by that war, and jihadism faded from the headlines. Many Isis supporters drifted away, and few new recruits emerged – partly because the security services had become far more effective at dismantling territorial networks, but also because few people wanted to join a movement that appeared to have lost.

That changed on 7 October 2023, with Hamas’s terrorist assault on Israel. Isis was not involved and remains a bitter rival of Hamas, which it regards as insufficiently Islamist. Yet the attack, and the subsequent war, unleashed a wave of anger across the Middle East and beyond, which Isis could not ignore. Three months later, the group issued its first official statement on the conflict, urging supporters to “strike the Jews wherever you can find them”.

The shift in emphasis was striking.

Unlike in the mid-2010s, Isis was no longer calling on its followers to travel to the Middle East to join a caliphate. Instead, it encouraged attacks everywhere – especially against Jewish people and targets associated with Israel. In effect, Isis was attempting to ride a wave created by October 7, even though it had played no role in the events themselves.

To some extent, this strategy worked. Recruitment no longer took place in backroom mosques or through radical preachers known to the authorities. It moved almost entirely online. The attackers who emerged were overwhelmingly so-called lone wolves with no prior connection to Isis, many of them very young. A new generation was forming, shaped less by battlefield victories than by viral propaganda, grievance, and algorithmic amplification.

The scale of violence has not come close to the jihadist wave of the mid-2010s, but the trend is unmistakeable. In the 12 months following October 7, the number of attempted and executed jihadist attacks in Europe rose by around 400 per cent. More than 40 per cent targeted Jewish or Israeli interests.

There were numerous attempts against synagogues, including the attack in Manchester, as well as a plot against the Israeli consulate general in Munich. One of the deadliest attacks before the Bondi Beach incident occurred in Solingen in August 2024, when an attacker killed three people at a city fete. In a video message, he claimed he had acted “for the people of Gaza”.

Isis, in other words, is seeking to capitalise on the conflict in the Middle East and is beginning to succeed. But its terror looks very different now from how it looked a decade ago. Without a caliphate, and with Western security services far more adept at disrupting networks and charismatic recruiters, its centre of gravity has shifted. Most attackers are not part of a formal command-and-control structure; even if some maintain loose connections with likeminded individuals elsewhere, these are mostly cultivated online.

This is where the current jihadist threat will be confronted. What role the Philippines had to play in this latest attack remains to be seen, but ultimately, the battlefield is no longer primarily physical territory, but the digital spaces where radicalisation now takes place, largely unseen and at speed. That is where Isis survives, and where it must be defeated again.

Professor Peter R Neumann is a professor of security studies at King’s College London and the author of ‘ISIS: The Inside Story’ (2015)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks