How GLP-1 drugs may be leading to new eating disorders

While other weight-loss drugs have caused similar problems, one expert said GLP-1 medications have a far greater impact

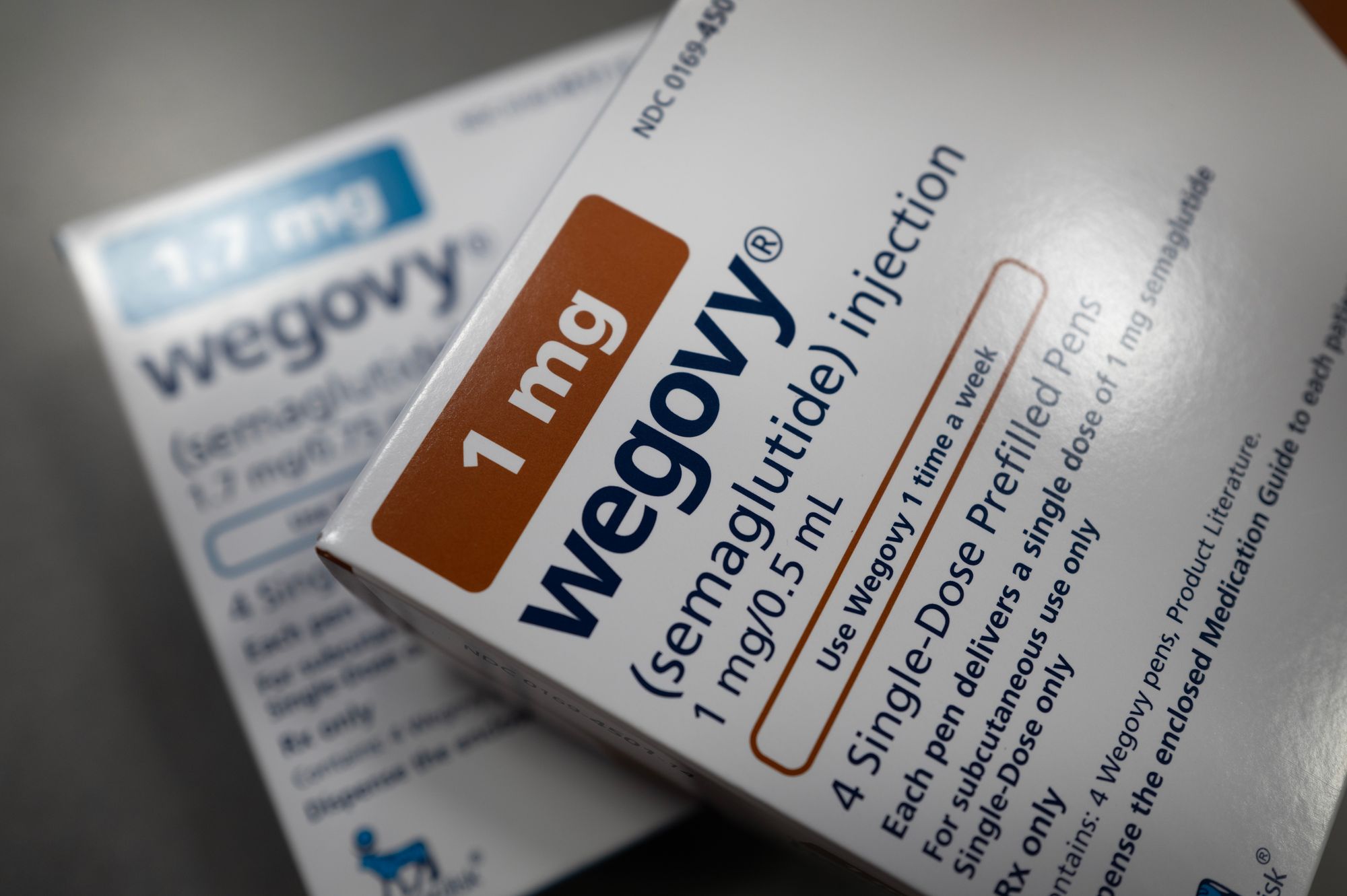

As millions of Americans take GLP‑1 medications like Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro for weight loss or diabetes, doctors are noticing that some patients are developing previously unrecognized eating disorders due to the drugs’ powerful appetite-suppressing effects.

Health professionals across the country say they are seeing patients whose relationship with food and body image has taken a dangerous turn since starting the medications, which some experts are calling a new form of disordered eating.

"GLP-1s are advertised everywhere and the ease of access through social media platforms, for example, is a concern,” Jillian Lampert, Vice President of Strategy and Public Affairs at The Emily Program, a national organization specializing in eating disorders, told The Independent.

“Responsible prescribing practices are essential to avoid adverse effects on individuals who could be at risk for developing an eating disorder. These individuals may suffer a relapse as a result of GLP-1 usage and the lack of proper screening and medical oversight,” Lampert added.

GLP‑1 medications are not FDA-approved for binge eating disorder or any eating disorder, according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Clinicians report that these emerging disorders often do not fit traditional categories such as anorexia, bulimia or BED.

"Some of the side effects of GLP-1 usage are gastrointestinal-related, such as nausea or vomiting. For those with bulimia, this can retrigger their eating disorder. It can make people who already have disordered eating tendencies or an eating disorder susceptible to relapse,” Lampert said.

Brad Smith, chief medical officer at The Emily Program, told the New York Post last month that some people prescribed these medications experience a resurgence of eating disorder symptoms, and others develop new or more severe eating disorders even if they had no prior history.

While similar issues have been observed with other weight-loss drugs, such as certain stimulants, Smith said that GLP‑1 medications are “a different animal” with a far greater impact.

“It’s exceeded anything in the past already,” Smith told The Post. “They’ve certainly had a much higher impact than any of those previous substances.”

The trend has alarmed eating-disorder specialists, who caution that current medical screening and monitoring may not be adequate to identify patients at risk. Many people prescribed GLP‑1 drugs are not evaluated for psychological vulnerabilities that could make appetite suppression dangerous.

Experts also say that stopping the medications does not always immediately reverse unhealthy eating patterns once they develop.

Research on the relationship between GLP‑1 receptor agonists and eating disorders is limited. Evidence suggests that by increasing satiety and suppressing hunger, these drugs may encourage dietary restriction, a known risk factor for disordered eating, especially among people already seeking weight-loss treatments.

Weight stigma may further worsen the problem, as people with higher body weight are more likely to be recommended weight-loss interventions, which can reinforce harmful thoughts and behaviors around food.

“To lead to weight loss, these medications are prescribed in two to five times the dose needed to treat diabetes,” Dr. Rebecca Boswell, Director of Penn Medicine Princeton Center for Eating Disorders and administrative director of Psychiatric Services at Princeton Medical Center, said at the Eating Disorders Research Society Conference in Sitges, Spain, last year.

“This is a massive dose of hormone that affects not only the gut, but the entire body, with major implications for eating processes and eating disorders. In addition, this treatment may prove to be unsustainable in the longer term,” Boswell added.

Eating disorders are also relatively common among people with diabetes. Between 12 percent and 40 percent of those with type 2 diabetes, and even higher rates in type 1 diabetes, experience disordered eating, according to Australia’s National Eating Disorders Collaboration.

For these patients, GLP‑1 medications may intersect with preexisting vulnerabilities, including fixation on food, restrictive behaviors or misuse of medications.

The National Eating Disorder Association says that research on GLP‑1 medications in people with eating disorders is scarce, leaving many unknowns. While the drugs are widely used for weight loss and diabetes management, it is unclear how they affect restrictive or binge-related eating disorders.

Clinical experience shows that recovery from eating disorders relies on consistent eating patterns, body acceptance, addressing weight stigma, tuning into hunger and fullness cues, and flexibility around food, but how GLP‑1 medications impact these recovery strategies is not well understood.

Existing studies are small and inconclusive. Some suggest the medications may reduce binge-eating episodes in patients with BED or bulimia nervosa, but sample sizes were limited, follow-up periods were short, and long-term effects remain unknown.

According to ANAD, the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, one randomized controlled trial found no significant changes in BED behaviors, indicating that GLP‑1 drugs may not address the root causes of eating disorders and that symptoms often return once the medication is discontinued.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks