The fight over Yasmin Khan’s ‘Sabzi’ and the woman who wants to trademark the word for ‘vegetable’

When a Cornish deli claims to ‘own’ a Farsi word spoken by a billion people, and a book with the same name disappears from Amazon, something’s gone badly wrong. Hannah Twiggs asks what this latest fight in the food world says about Britain’s uneasy relationship with cultural appropriation

When a word that literally means “vegetables” becomes the subject of a legal dispute, you start to wonder whether Britain’s food culture has finally eaten itself.

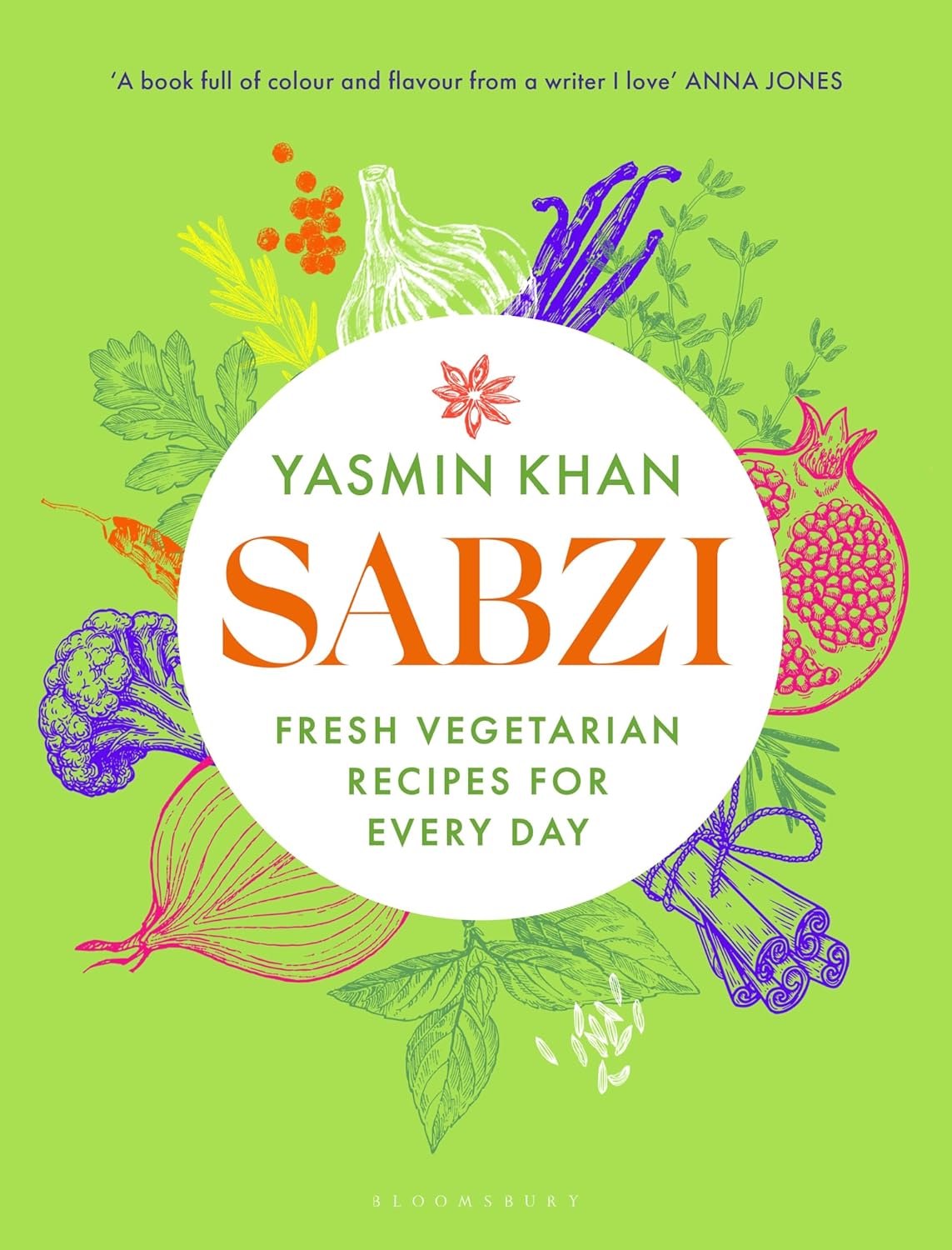

Last week, it was reported that Yasmin Khan’s latest cookbook, Sabzi, had been pulled from Amazon after a Cornish deli of the same name accused her publisher, Bloomsbury, of trademark infringement.

For anyone familiar with Khan’s work – elegant, soulful books such as The Saffron Tales and Zaitoun, which trace the flavours of Iran, Palestine and beyond – it felt surreal. Here was one of Britain’s most respected food writers, a woman of Iranian and Pakistani descent whose books have helped demystify and celebrate regional cuisines, now tangled in a row over a word so ordinary that more than a billion people use it every day.

Kate Attlee, the 37-year-old owner of Sabzi deli, said that Bloomsbury’s decision to publish a book of the same name had caused confusion among her customers. She founded her business in 2019 and trademarked the word “sabzi” in 2022, later discovering that Khan’s book had been released under the same title. Some customers, she said, had come into her shops asking for the book, assuming it was hers. “I just want them to respect the trademark and the future of my business,” she said.

Bloomsbury, for its part, argues that “sabzi” is a descriptive term, not a brand name – and, crucially, that Khan began work on the book in 2017, two years before Attlee’s first deli opened. In a statement, the publisher said the word is “part of the shared culinary vocabulary of many cultures, including Ms Khan’s own heritage”, meaning vegetables or greens in languages such as Farsi and Urdu, and commonly used in UK restaurants to describe vegetable dishes.

The publisher added that Sabzi consists of vegetarian recipes inspired by Iranian and South Asian traditions, and that “it is widely accepted that the use of a descriptive term as the title of a book in order to denote the book’s subject matter – as Ms Khan has done – does not function as trademark use”.

In other words, Bloomsbury says you can’t own vegetables.

And yet, in the eyes of the UK Intellectual Property Office, Attlee does – at least for now. Which raises a larger, more uncomfortable question: how did a Farsi word spoken by millions in Britain, and billions more around the world, come to be treated as an original brand name?

Food writer Rukmini Iyer, whose own Indian heritage gives her more than passing familiarity with the term, captured the disbelief in a Substack post: “OVER ONE BILLION PEOPLE use the word ‘sabzi’ daily,” she wrote. “And they aren’t talking about a deli.” She pointed out that a quick search on Deliveroo reveals dozens of sabzis available for delivery in any British city. “It’s like getting a trademark for a fish shop called ‘Fish’,” she added, “and then posting out lawsuits when someone publishes cookbooks called ‘Fish’ or ‘Pies’.”

It seems to me that she’s right – but the problem is more systemic than one bad decision. Under UK law, a trademark cannot be “descriptive or non-distinctive”, meaning you can’t normally register a word that simply describes what you sell. But there’s a catch: the test is based on the understanding of the “average UK consumer”. If that consumer doesn’t know what “sabzi” means, the term might appear distinctive enough to be granted. In short, the law is written for monolingual Britain, and hasn’t quite caught up with the multilingual one we actually live in.

Once registered, a trademark can be challenged or cancelled if it’s proven to be generic or commonly used, which may well be the outcome here. But the fact it got through at all surely exposes a flaw in how British institutions treat non-English words: as exotic, ownable and somehow up for grabs. As Iyer’s neighbour – an intellectual property lawyer she consulted – pointed out, an examiner in Newport, Wales, may not know Urdu well enough to recognise that “sabzi” simply means “vegetables”.

The result is a kind of cultural absurdity unique to modern Britain: a word that’s been part of daily speech in homes, markets and menus for generations suddenly being treated as property. As Iranian-Italian author Saghar Setareh put it in a furious post: “It’s like trademarking the word taco, or curry, or pie. Words are not our personal property. We cannot own them.”

Setareh went further, calling the case “insane” and “absolutely ridiculous”. In her view, the trademark isn’t just a bureaucratic oddity but a failure of cultural literacy. “Sabzi means greens/herbs/vegetables in Persian, Urdu, Hindi and all the related languages and variations of it appear in Turkish (sebze) and other languages,” she wrote.

Australian-Chinese author Hetty Lui McKinnon echoed the sentiment, describing the situation as “completely mad”. Meanwhile, journalist India Knight wrote: “This story is absolutely deranged. You can’t ‘own’ a word that a billion people use every day … It means VEGETABLES!”

OVER ONE BILLION PEOPLE use the word ‘sabzi’ daily. And they aren’t talking about a deli

The outrage, though, is about more than one lawsuit. It’s a cumulative exasperation – the sense that Britain keeps having this same argument about who owns food, and who gets to speak its language. We’ve been here before. In May last year, the British-founded restaurant chain Pho was forced to surrender its UK trademark on the word “pho” after a London-based Vietnamese influencer ignited public anger over its claim to the country’s national dish.

The Pho example is particularly instructive. Founded by a British couple who fell in love with Vietnamese food while travelling, the chain trademarked “pho” back in 2007, when the dish was still unfamiliar to many in the UK. But when the company began sending legal letters to smaller restaurants with “pho” in their names, it sparked outrage. The brand eventually apologised and relinquished the trademark.

That’s why the Sabzi situation feels like deja vu, but with higher stakes. It’s not just about a company trying to own a word. It’s about someone claiming ownership of a word that predates their business, their trademark and perhaps even their own understanding of it. The fact that Khan herself is of Iranian and Pakistani descent only sharpens the irony: this isn’t cultural appropriation in the traditional sense, but feels to me like a kind of bureaucratic colonisation, where language is flattened into a line on a form.

Legally, Attlee may have a point: she trademarked the name to protect her business, not to attack others. Bloomsbury’s decision to temporarily delist Sabzi from Amazon, even before any ruling has been made, feels like an act of corporate caution rather than conviction. It’s not the first time a publisher has bowed to online pressure, but it might be the first time it’s happened over a word as benign as “vegetables”.

For all the noise, there’s still a degree of sympathy to be had for small business owners trying to carve out a space in an unforgiving market. Attlee’s delis are, by all accounts, well-loved; she’s said she respects Khan and doesn’t want profit, only recognition of her brand. But, in the opinion of many, the moment she turned a shared cultural word into intellectual property, she crossed into territory that feels at odds with the very spirit of food: communal, plural, generous.

Because food language, like food itself, doesn’t belong to anyone. It evolves through use, migration, memory; through grandmothers and street vendors, not trademark lawyers. And yet time and again, we watch as it’s flattened into something marketable, something ownable, something you can stick on a label and claim as yours.

If there’s one thing this latest row proves, it’s that Britain still hasn’t learnt how to talk about food that isn’t its own. When the legal system doesn’t recognise that “sabzi” means vegetables, when corporations seem too nervous to fight for the obvious, when a cookbook has to disappear to avoid offending a trademark, maybe it’s not just the food world that’s lost perspective.

After all, if vegetables can be trademarked, what hope is there for everything else?

The Independent has contacted Kate Attlee for a comment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks