The Great Re-education: Why over-40s like me are quitting careers and heading back to school

As AI, insecurity and burnout reshape the job market, a growing number of midlife professionals are returning to university, says Lotte Jeffs. Retraining is becoming less of a risk – and more of a necessity

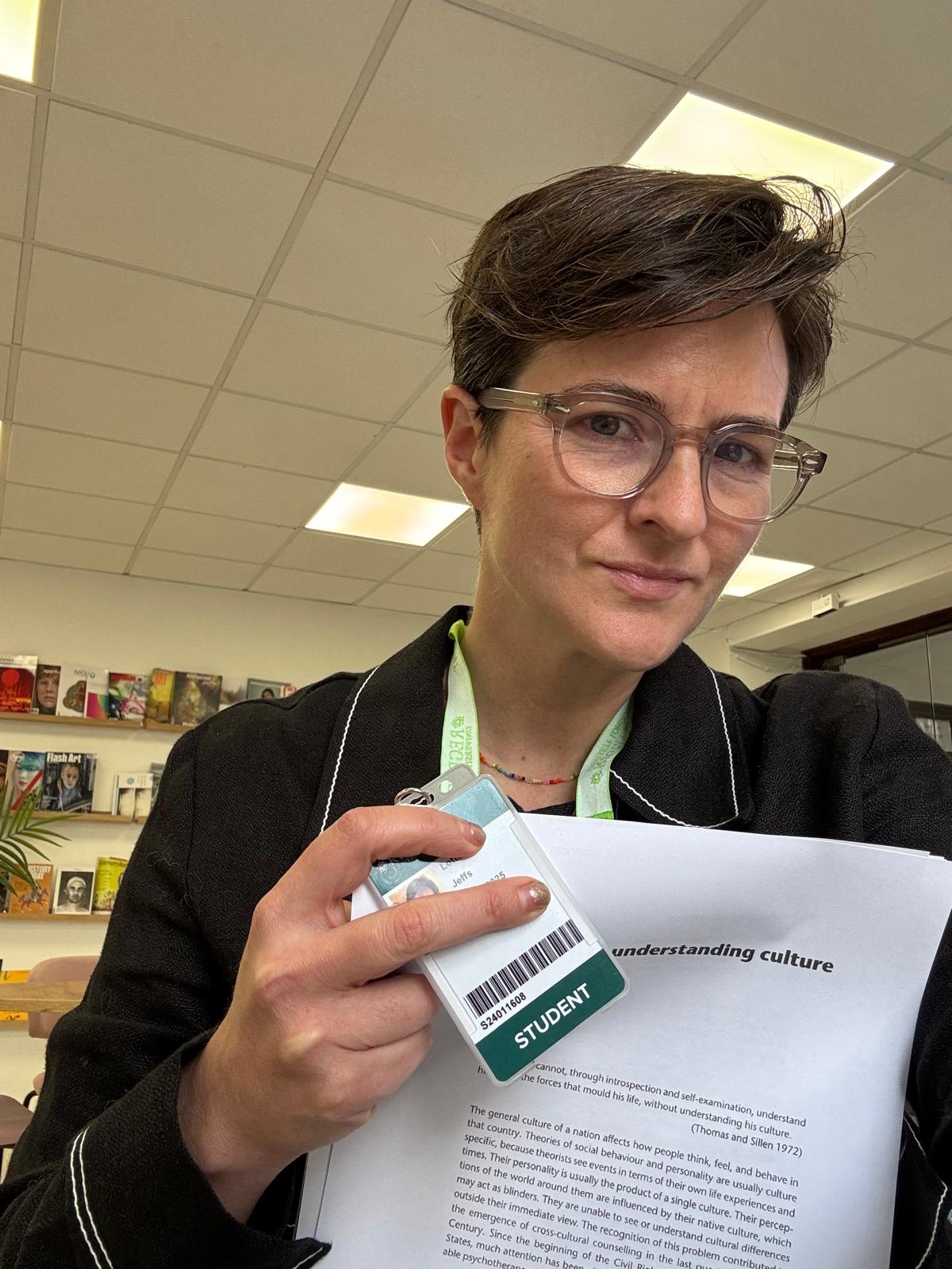

I’d bought a new pencil case especially, diligently made a packed lunch the night before, and was setting off for my first day at university with a rucksack on my back and a lanyard swishing around my neck. What would my classmates be like? What about the lecturers? And, at 42, would I be the oldest student in my cohort?

Going back to study psychotherapy after a successful career as a magazine editor (of Elle magazine) and writer (of four books) came with plenty of anxieties. But as I walked through Regent’s Park towards the elegant redbrick building that would become my place of learning for the next four years, what I felt most strongly was relief – relief that I had a plan, and was working towards a new career that might, just about, see me into my old age.

I’m far from alone. Across the UK, a surge of people are returning to education, often at great financial cost (you’re looking at upwards of £10k a year for an MA), in search of something more stable, more meaningful, or simply more survivable than the work they once relied on. We’re juggling jobs, families and caring responsibilities to make the leap – and taking on huge debts to do so.

In 2022, more than 244,000 mature students were enrolled in UK universities, according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency, with the number of students aged 30+ starting degrees rising every year, particularly in healthcare, education and business.

At a point when many of our peers are supposedly at their peak earning potential, some of us are choosing – in pursuit of longer-term security – to step sideways. Or backwards. Or straight into the unknown. Thankfully, sitting with uncertainty is a core part of my psychotherapy training.

My decision to retrain followed a professionally panic-inducing year. My non-fiction book proposal didn’t sell (if you’re not a celebrity or influencer, publishing anything right now feels brutally hard). The rapid spread of AI meant much of the copywriting, tone-of-voice and consultancy work I’d previously been paid well for dried up almost overnight. Meanwhile, a rollback of diversity and inclusion projects in the US curtailed the speaking and advisory work I’d enjoyed, while global economic uncertainty saw several regular freelance contracts disappear.

Before my annus horribilis, I’d been living a comfortable freelance life, taking luxury holidays and dinners out for granted. Then, suddenly, I was researching grants and loans and borrowing money from my 80-year-old mum. I was still being commissioned to write, but as any journalist in the UK will tell you, that alone won’t cover a mortgage.

After two decades spent working towards seniority in the creative industries, it was dispiriting to find myself applying for roles far below my experience and pay grade. Leadership jobs in media were thin on the ground, and after five years freelance I struggled to get back in. So I parked my ego and sent my CV out for retail and admin roles – the sort of jobs I’d last done in my early twenties.

The lowest point came when I was rejected for a part-time barista role at Benugo, the cafe chain. I’d run magazines, led teams and won awards – and yet I was deemed unsuitable to make coffee. I couldn’t go on like that. So I decided to do something that might not only safeguard my future working life, but also restore a sense of meaning at a moment when everything felt bleak.

Yes, ChatGPT is coming for psychotherapy too. There are near-daily headlines about people turning to AI for emotional support. But the relational core of therapy – embodied presence, attunement, messy humanity – isn’t something you can replicate with a bot. However advanced these systems become, I believe people will continue to pay for the privilege of 50 minutes with a trained human therapist. At least, that’s what me and the other second-career life-pivoters on my MA course tell ourselves.

.jpg)

And no – I’m not the oldest in the room. Our cohort spans early thirties to mid-sixties. We’ve arrived from law, teaching, fashion, tech, journalism, parenting, burnout, redundancy and grief. Each of us is hoping that studying something new will help us build a future more resilient than the one we felt slipping away.

After a year of training together, we’ve grown deeply attached. Their support carried me through one of the most professionally challenging years of my life. We bonded over the joy of studying again at this stage – and over how different we are from the undergraduates, who at this particularly bougie London university dress like extras from Emily in Paris. I’ve overheard endless conversations about private jets and couture while queueing for the canteen. I’m also regularly mistaken for a lecturer and asked for directions.

There are quieter pleasures, too. Submitting an essay without worrying about how it will “perform” online. Learning to read slowly again. Discovering – sometimes uncomfortably – what happens when you turn your analytical skills inward.

Retraining has given me back a sense of direction that isn’t dictated solely by the market. It’s reminded me that my working life can still evolve rather than contract. Going back to university at 42 has taught me that starting again isn’t failure. If anything, it’s catching on: since completing my first year, I know at least six other journalists and fashion editors who’ve made the same move.

As unemployment rises and “old media” struggles in a world of TikTok videos and AI, it’s hardly surprising that some of the industry’s most talented people are asking how their skills might transfer – and heading back to school for a second act.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks