Junior doctors like me aren’t greedy – we’re fighting to save the NHS

Two-thirds of doctors are planning to leave the UK. Wes Streeting can call it preposterous, says Dr Holly Tarn – but it’s his government that’s driving them out

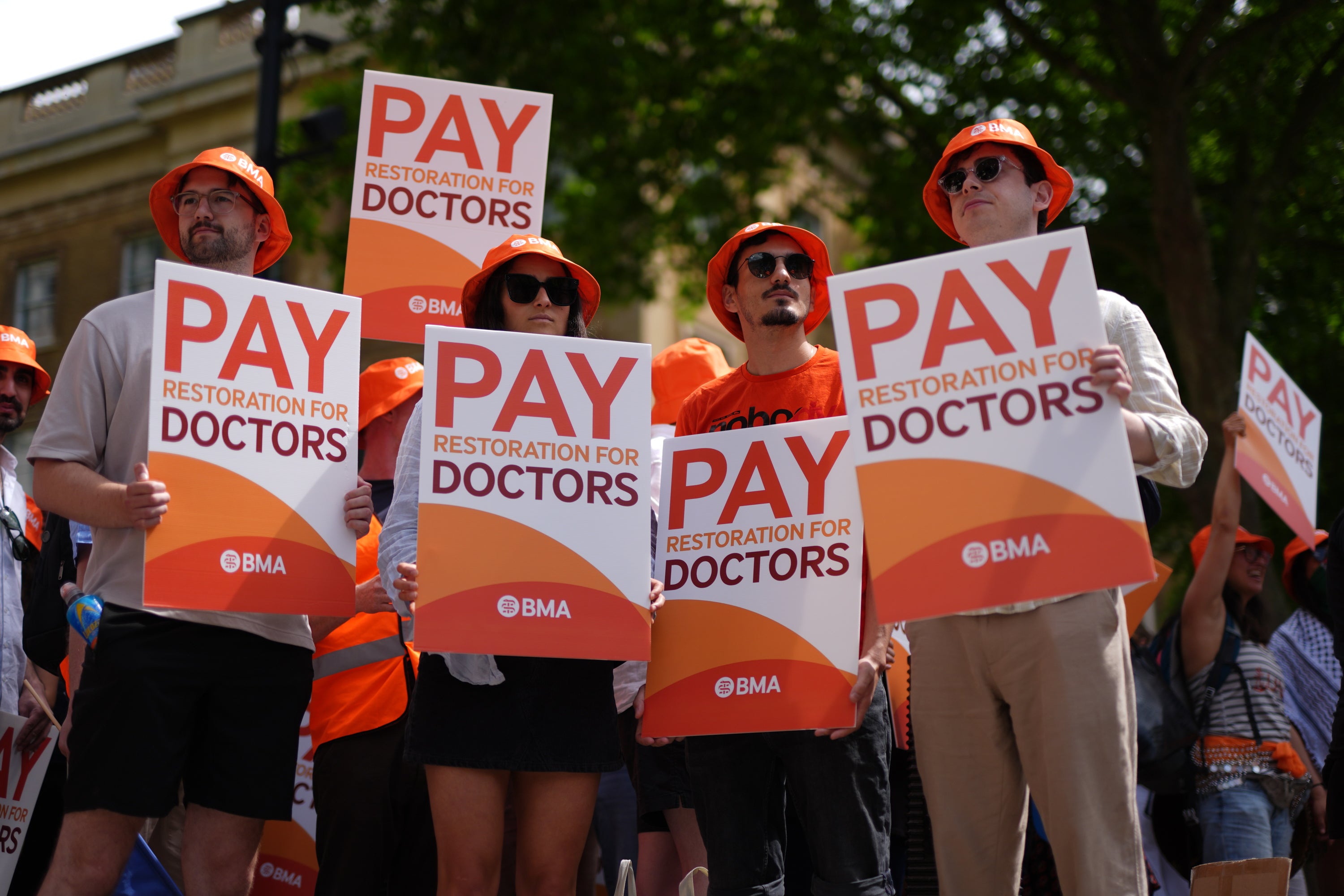

I know this news will come as a slap in the face for patients,” said health secretary Wes Streeting, talking about the news of renewed strike action, which I’m seeing – of all places – on my Instagram reel. That makes the attack feel ever so slightly more personal.

A newly qualified full-time doctor like me earns £38,831. In real terms, that’s about 20 per cent less than in 2008. Adjust for the 1980s, and doctors were effectively earning what would be £85,000 today. So this kind of thing sticks in my craw.

Streeting insists doctors have been given enough. No further pay deal is on the table. Any new strike, he says, would be “preposterous”. But why is it? Those numbers alone tell a different story.

Years of below-inflation settlements have quietly stripped value from our pay. Even if the government kept pace with inflation from now on, it would take more than a decade to restore our salaries to where they were in 2008.

Critics argue all public sector jobs have faced cuts. But not all cuts are equal. MPs’ pay, for instance, remains broadly in line with 2008 levels in real terms, and still more than twice my own salary.

Then there are the other costs, the ones rarely mentioned outside the profession. I left university £50,000 in debt from tuition fees alone. Those debts follow us throughout our careers.

Doctors are expected to pay for the privilege of progressing – postgraduate exams costing over £1,000 each, self-funded conferences, constant relocations, and compulsory memberships and indemnity fees, many of which should be reimbursed but rarely are.

A National Institute for Health study found the average unreimbursed cost for a junior doctor exceeds £18,000. A few days ago, Streeting pledged to cover mandatory exam and membership fees as part of his latest offer. It’s a welcome gesture, but against the eye-watering personal cost of simply training, it feels like a drop in the ocean.

The training years of a doctor are unforgiving, yet it’s resident doctors (alongside our nurses and fellow healthcare workers) who keep our hospitals running. Through nights, weekends and holidays, we shoulder the weight of life and death. We resuscitate your children, deliver heartbreaking news and make impossible decisions on too little sleep.

But soon you’ll be a consultant – sitting back, financially secure and laughing at the stress of your training years, right? Wrong.

On average, it takes between eight and 12 years to move beyond “resident” status, and the thing making this decade so bleak isn’t just the pay. A crisis of morale is afflicting new NHS doctors – one so bad that not even the self-care email from management advertising fortnightly Pilates classes on offer could possibly fix.

In the 2025 turnover, more than half of junior doctors faced unemployment at the end of their two-year foundation contracts, largely due to bottlenecks in specialty training places. They work themselves to the bone only to find themselves without a job to progress into.

The competition has become brutal. In 2020, A&E had just over one applicant per post; by 2025, there were 14. You’d think this would be a good thing: there is a generation of doctors bursting with talent just waiting for the system to make space for them. We know the NHS is overstretched, and we want to work. But while medical school places keep rising, training posts haven’t kept pace.

Streeting has additionally offered to expand training posts – first by 1,000, then by 2,000 in a bid to deter strikes. To meet current demand, we’d need closer to 20,000 new training places. The offer doesn’t touch the sides.

And while countless doctors struggle to secure work, patients struggle just as hard to secure a doctor.

Anyone who has sat on a waiting list for an outpatient appointment or endured the relentless drone of on-hold GP music knows that these gaps in care are not the fault of striking resident doctors.

They are the consequence of a government that refuses to acknowledge the need for more, better-trained doctors – doctors who stay in the system. The UK has fewer doctors per capita than 18 other European countries, including Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia. And we’re leaving in our droves.

Last year, 10,685 doctors left the NHS – the highest number on record. The reasons are depressingly familiar: poor pay and working conditions, and the growing sense of being undervalued.

A recent survey found that one in three doctors is “very likely” or “fairly likely” to relocate abroad within the next 12 months, with another 30 per cent saying they expect to leave at some point in the future. To put it bluntly – two-thirds of our doctors are making plans to leave the country.

But I don’t want to move to Australia or Canada. I want to stay and work in the country where I was born and trained, and where I still believe in the promise of the NHS. To do that, though, I – and thousands of others like me – need a more serious effort towards full pay restoration and an overhaul of our training system and workforce strategy.

Full pay restoration isn’t a slogan – it’s a survival strategy. Fair pay means retention. It means fewer burned-out doctors leaving mid-career. It means more stable teams, safer wards and shorter waiting lists.

We aren’t striking out of greed. We’re striking because the system is running out of doctors – and we are running out of reasons to stay.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks