How a boycott America movement is starting to work against Trump

Could a boycott of US products and services actually send a message to the Trump administration? Katie Rosseinsky looks at how peaceful protest can bring real change and the ‘3.5 per cent rule’ that can shift the dial

Coca-Cola. Netflix. Google. Apple. Amazon. McDonald’s. Starbucks. These are just a handful of the US mega-brands that many of us use or spend money on every single day. But for some Brits, that’s no longer the case. They might not be able to let President Trump know exactly what they think of his policies, but what they can do is put their money where their mouth is and boycott American companies.

Activist and content creator Caroline has been “actively trying not to support the USA for around a decade now”, after “learning about imperialism, capitalism, corporate giants and the fact that [the US] has largely monopolised the world”. She has been boycotting “big US brands” – McDonald’s, Amazon, Starbucks – for as long as she can remember, but after the recent events in America, and comments by the US president, she has noticed a real sea change in attitudes.

When she has previously expressed her opinions about it online, she’s been “met with ridicule or criticism”. But when she posted a now-viral TikTok video earlier this month about “how to boycott America”, “the vast majority of people agreed, particularly people within the USA”.

“Even Americans themselves are saying the best way to help them is to boycott,” Caroline adds. “We should listen to that.” Because “America is driven by cash”, she argues, “we need to speak its language. People think boycotts don’t work, but they do if we take collective action.”

For support worker Sally*, the catalyst was the heartbreaking image of five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos, seen around the world last week. The youngster, pictured wearing a blue bunny hat and a Spider-Man backpack, was taken from outside his home in Minneapolis by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers last week, along with his father, Adrian.

The family had an active asylum case after arriving in the US from Ecuador, and had no deportation order against them, according to their attorney. The Department of Homeland Security, meanwhile, described Liam’s father as an “illegal alien”. “I cannot get his face out of my mind, and felt I had to do something,” says Sally.

So, she and her family are concentrating on quitting a few “hi-vis” American brands, like Coca-Cola. “I won’t buy it, serve it to friends or order it ever again,” she says. American alcohol is now off-limits, too, plus they’ve “decided not to travel to the USA for holidays until this horror has passed”.

“We used to visit roughly every two years, spending around £5,000 a time. We have many lovely American friends and adore their beautiful national parks, but have decided to go elsewhere,” she tells me, hopeful that “these actions will, collectively, give the US public cause for thought to demand policy changes from their president”.

Fifty-five-year-old author and speaker Vie Portland has taken a similar approach. “When Trump came into power again, we didn’t want to do anything that would line his and his allies’ pockets, so we started exploring more companies [to boycott],” she says.

She has since stopped buying from the likes of Coca-Cola and Pepsi, instead going for soft drinks from Salaam Cola, Karma Drinks or UK-based companies. Domino’s, Papa Johns, Starbucks and Costa (owned by the Coca-Cola Company) are also on her no-buy list. “We haven’t found a good alternative to takeaway pizza, but that’s probably a good thing. And it’s always better to support local cafes.”

Even Americans themselves are saying the best way to help them is to boycott

Since Trump’s second inauguration last January, a “series of cumulative events” has prompted some Brits to reassess where their money is going, says Dr Matthew Mokhefi-Ashton, lecturer in politics and the media at Nottingham Trent University. Last year saw the president impose tariffs on British imports (which he has since threatened to crank up), and, more recently, Trump’s fixation with annexing Greenland from Denmark, along with the ICE raids, has raised yet more concerns.

Trump’s recent comments about Nato troops marked another “absolute turning point” for many consumers, too, Mokhefi-Ashton says. Last week, the president claimed that non-US soldiers had “stayed a little back, a little off the front lines” in conflict – a statement that inevitably sparked anger. In a trademark U-turn, he later walked back his words, singling out the “GREAT and very BRAVE soldiers of the United Kingdom” as being “among the greatest of all warriors” in a post on Truth Social.

But the harm had already been done: his remarks, Mokhefi-Ashton adds, were “hugely damaging”, and will have prompted “people who up until that point hadn’t really thought about boycotting the US”, and might even have been “quite supportive” of America, to “seriously start thinking about it, and think, ‘What differences could I make?’”

Other countries have something of a head start when it comes to boycotting Trump’s America. Canadians, Mokhefi-Ashton notes, have understandably been less than impressed “by his implications that he’d like them to be the 51st state”, and his disparaging references to their prime minister as a “governor”. Tariffs, too, have caused bad feeling.

“It’s a proud, independent country,” Mokhefi-Ashton says. “To be belittled in this way by their closest neighbour – it’s hard to see any country not taking that incredibly badly, and saying, ‘This is going to translate into genuine action.’” In the first nine months of 2025, Canadian visitor numbers to the US dropped by 22 per cent year-on-year, while sales of US wine have dropped by a staggering 91 per cent since 2024.

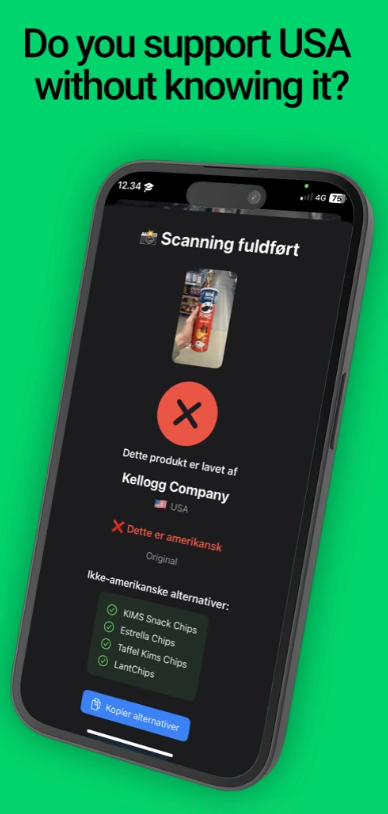

And in Denmark, an app called UdenUSA (NonUSA in English) has leapt to the top of Apple’s App Store charts (yes, there is a certain irony to the Apple of it all, but no boycott is perfect). It allows users to scan groceries and other products to check whether they are American-made; the logic is that shoppers can then put that brand back on the shelf and spend their kroner on a Danish or European alternative. “Every time you buy an American product, you indirectly support a system that works against many of the values we cherish in Europe,” its website reads.

It can be difficult to measure the impact of customer-level boycotts, Mokhefi-Ashton explains. And, he adds, “the US economy is so massive compared to ours [in the UK] that, purely on an individual level, the average person’s boycotting doesn’t actually make that much of an economic impact”. Instead, he says, “it plays more into the symbolism” of “saying ‘This is something concrete that I can do, so I’m doing my part.’” Portland agrees. “I know the small amount we were spending on these things won’t make any difference to the companies, but I believe strongly in the power of ‘us’ as a whole community,” she says.

Indeed, none of the boycotters I speak to have any illusions about being able to entirely detach their lives from the US economy. Portland is self-employed and relies on (US-owned) social media to promote her business. Caroline, meanwhile, is aware that, working in social media and content creation, “the majority of companies that hire me, or platforms that I use, are American-owned”. But, she says, “unless you live off grid, I’d argue that a total boycott of America and its products is impossible. That is late-stage capitalism for you.”

However, tourism might be “one area where potentially boycotting could make a difference”, Mokhefi-Ashton says. Reports of travellers being detained at the border and proposed policies about social-media screening have made the US seem like a far less desirable destination. A recent poll posted by The Independent’s travel expert Simon Calder on Twitter/X found that four out of five of the 12,000 self-selecting respondents wouldn’t currently travel to the US.

Foreigners refusing to travel to the US equates directly with less money being spent there. Last year, a report by the World Travel and Tourism Council estimated that the US would lose $12.5bn (£9bn) in international visitor spending in 2025. It’s also, frankly, a very easy boycott: you can simply decide to go elsewhere, or to postpone your trip until someone else is in office.

And for those who are sceptical about whether seemingly small actions can ever really make a difference? Consider the 3.5 per cent rule, a concept developed by Harvard political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan. After analysing non-violent resistance movements throughout history, they concluded that peaceful protests mobilising just 3.5 per cent of a country’s population (that’s about one in every 35 people) tend to achieve their goals and bring about change. As Chenoweth has put it, “a surprisingly small proportion of the population guarantees a successful campaign”.

The US population is approximately 333 million, so 3.5 per cent would be roughly 11 to 12 million people – the population of Greater Los Angeles. In the UK, 3.5 per cent would equate to around 2.45 million people. That’s just a bit less than the entire population of Manchester. So it’s not an insignificant figure, by any means. But it’s probably far smaller than the number you might initially have thought would make a real difference – and perhaps compelling proof that “doing your bit” isn’t futile.

Just one person performing one immaculate boycott “won’t make a dent”, Caroline reckons. But “all of us collectively boycotting even a fraction of what we [used] before will”. And she has a message for those who think these changes won’t make a difference at all. “I hope you stop admitting defeat and join the movement for a better world eventually. We will be waiting for you when you’re ready.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks