From slogans to Greg Bovino’s uniform – the Nazification of ICE shouldn’t be underestimated

History may not repeat itself, but it echoes, and the 1930s taught us why symbolism matters. Fascism did not arrive with a single marching column, says historian Guy Walters, it arrived by making brutality feel normal, even noble. You don’t have to hear jackboots to recognise the direction of travel – the signs are everywhere

It is one of the oldest tricks in the authoritarian playbook: aesthetic first, policy second. Before the mass arrests, before the street violence, before the bureaucracy hardens into a machine, you soften the ground with imagery that makes the coming crackdowns feel righteous, necessary – inevitable. That is why it matters, urgently, that America’s immigration enforcement apparatus is now recruiting in a visual and rhetorical register that looks, sounds and feels uncomfortably like the 1930s: the decade in which fascism stopped being a crank ideology and became a governing reality.

Let’s be clear: the posters and social-media graphics pushing people towards US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) jobs are not merely a bit retro. They are saturated with the grammar of Nazi and far-right propaganda; heroic silhouettes, blunt moral binaries, looming national decline and the call to defend a mythic “homeland”. And this all arrives at a moment when federal agents are killing US citizens on American streets.

The killing of Alex Pretti, a 37-year-old ICU nurse and US citizen, who was shot by US Border Patrol agents in Minneapolis, Minnesota, over the weekend, shocked the world. His colleagues and family describe him as a compassionate healthcare professional, and despite a statement by Kristi Noem, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) secretary, saying he was armed with a handgun, he was holding a phone, not a weapon, at the time he was pepper-sprayed, tackled and shot by federal agents.

Renée Good, a 37-year-old American citizen, was also fatally shot in Minneapolis, Minnesota, by United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement two weeks before Alex Pretti was killed. These two citizen deaths are unlikely to be the last at the hands of ICE and many more American citizens have been and will be injured. For an increasing number of onlookers, this is all the bloody result of a recruitment drive that prioritises muscle over training, and whose messaging carries serious fascist overtones.

History might not repeat exactly, but it certainly rhymes. One of the most widely circulated recruitment images for ICE shows Uncle Sam, not rallying for a war abroad but apparently dithering at a crossroads: one direction labelled with virtuous abstractions – “HOMELAND”, “SERVICE”, “OPPORTUNITY” – the other with dread – “INVASION”, “CULTURAL DECLINE”. It is classic mobilisation art: a simplified nation-persona confronted by existential choice, reduced to signposts and slogans.

The image was posted by the DHS, along with the words, “Which way, American man?”, which was clearly a deliberate nod to the book Which Way, Western Man?, a vile 700-page tome by William Gayley Simpson and published by a neo-Nazi press back in the 1970s. As the book claimed that non-whites are a threat to the very existence of America, there can be no doubt that the words chosen to accompany the poster were designed to appeal to those who decide “real Americans” along racial lines.

Just one day after Renee Good was fatally shot by an ICE agent, the podium where Kristi Noem gave her press briefing was emblazoned with the slogan “One of ours, all of yours”. This phrase is strongly associated with Nazi ideology and SS collective-punishment doctrine, where, during the Third Reich, the killing or arrest of one German soldier would trigger retaliation against civilians (often expressed as “for one German, ten/one hundred locals”). While the DHS denied using literal Nazi propaganda and called the accusation of it being Nazi messaging “tiresome”, critics still believe the wording was deliberate aggressive rhetoric about retaliation or collective punishment.

There is also the poster showing ICE agents as heroic medieval knights, along with the caption, “The enemies are at the gates”. Nazi propaganda, too, just loved depicting members of the SS as knights in armour, ready to protect a sacred homeland from invasion.

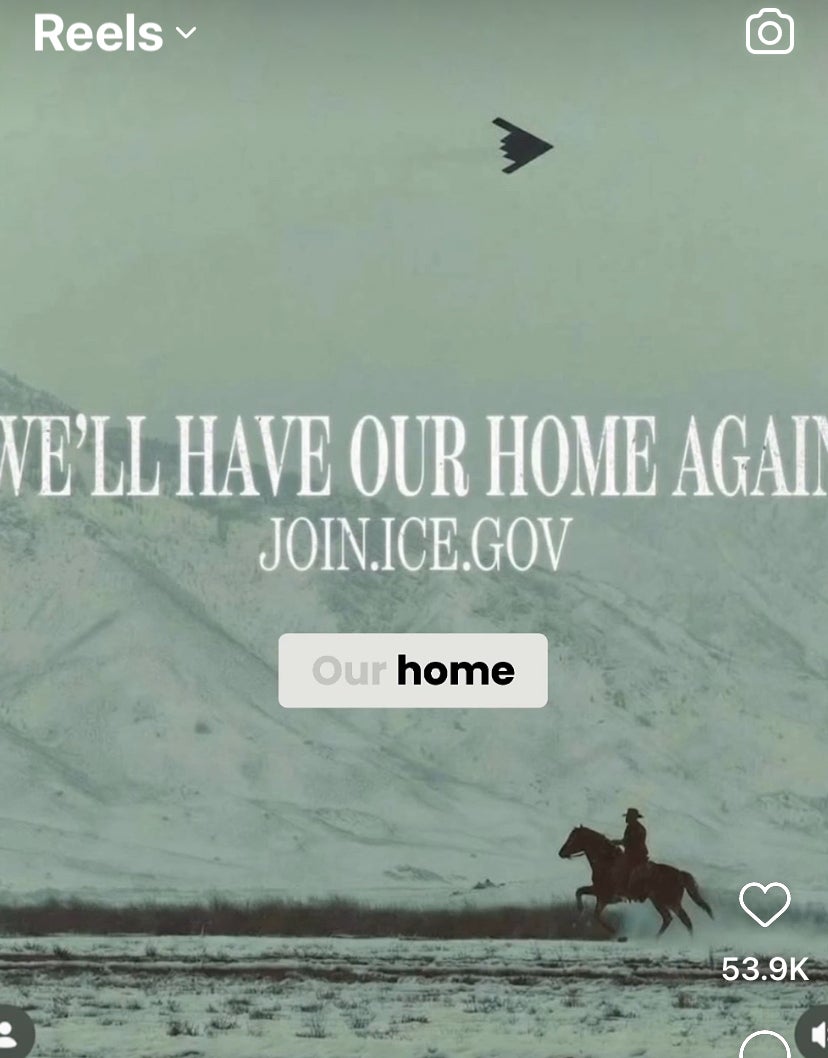

Or how about the poster showing the lone silhouette of a cowboy set against a mountain range, above which flies a stealth fighter, and emblazoned with the words, “We’ll have our home again”? The line is the title of a song by the Pine Tree Riots – a band beloved by white nationalists – and which features the lyrics: “In our own towns, we’re foreigners now/ Our names are spat and cursed/ The headline smack, of another attack/ Not the last, and not the worst/ Oh my fathers, they look down on me/ I wonder what they feel/ To see their noble sons driven down beneath a coward’s heel”.

There can be no doubt that the recruitment aesthetic is being tuned to resonate inside a far-right cultural frequency – one in which “invasion”, “decline” and “homeland” are not neutral words but ideological dog whistles.

Why do these phrases matter so much? Because in white supremacist subcultures, “homeland” is rarely just a place. It is an imagined ethno-state – an all-white inheritance threatened by outsiders, upheld by force. “Invasion” is not merely a metaphor for border crossings; it is straight out of the “replacement theory” conspiracy handbook, which claims that non-white migration is a coordinated assault on Western civilisation. With these messages, you are no longer recruiting for law enforcement. You are recruiting for an all-out culture war.

And it is all so very 1930s. Not simply because the graphics borrow the stark, posterised look of interwar recruitment art, but because the emotional structure is the same: a beloved national community said to be on the brink, endangered by “outsiders” and “decadence”, requiring a cadre of tough men to restore order. Fascist movements also sold themselves as saviours rather than vandals.

If you want an embodiment of this aesthetic, look no further than Gregory Bovino, the senior Border Patrol figure who has become a recognisable face of the new enforcement posture. His distinctive brass-buttoned, calf-length greatcoat resonates with a “fascist” aesthetic. Along with his Himmler-like haircut, Bovino basically looks like he is cosplaying a senior SS officer, and does so while presiding over aggressive raids in the name of his country.

As the backlash grows over the killing of 37-year-old nurse Alex Pretti, it is being reported that Gregory Bovino and other federal agents are set to depart from Minneapolis. It is right that historians should be cautious with analogies, but we should not be timid. The SA – Hitler’s stormtroopers – although never an extermination unit per se, certainly created the atmosphere currently being invoked on the streets of America. They were a continual presence of street muscle, normalising violence, intimidating communities, and creating a constant and ambient fear that made normal life feel impossible. They terrorised Jewish neighbourhoods, smashed businesses, beat opponents, and taught ordinary people that the state would not protect them.

There are obvious differences between Nazi Germany and the United States in 2026. Yet there is a chilling familiarity in the pattern whereby a state-aligned force is encouraged – through imagery and nationalistic rhetoric – to see itself as the guardian of an ethnically defined nation, and to intentionally impose order through fear.

Against this backdrop, the recruitment imagery curdles into something darker. It is one thing to romanticise enforcement as “service” in the abstract; it is another to do so while agents, operating under the banner of immigration control, are, according to multiple reports, shutting out local scrutiny of the violence being imposed on communities. Through this lens, it is hard to escape the sense that the posters are not incidental marketing, but part of a broader political project: to create a self-selecting, ideologically hardened corps who see their work not as paperwork and arrests, but as a pitched battle for the nation.

Recruitment material that idealises a threatened “homeland” tends, in practice, to picture that homeland as racially homogenous. When the enemy is framed as “invasion”, the invader is understood to be non-white. When the mission is to arrest “illegals”, the public imagination – shaped by years of rhetoric – defaults to brown bodies.

And so much of the messaging which surrounds what some are dubbing “Trump’s private army” reads as an invitation to enforce racial boundaries, not merely legal ones. It implicitly promotes the idea of an all-white homeland under siege, implying that ICE agents are targeting non-white people to “save” it. You do not need to write “white” on a poster for white supremacists to hear it. They have long trained themselves to decode, and the DHS knows it.

The defenders of these campaigns say critics are seeing Nazis everywhere; they argue that the Uncle Sam figure is simply Americana, that “homeland” is a neutral word. To object to this is to be paranoid and melodramatic. But the 1930s taught us precisely why symbolism matters. Fascism did not arrive with a single marching column; it arrived by making brutality feel normal, even noble.

When official government campaigns flirt with far-right iconography and coded language, while federal agents kill citizens and communities describe being terrorised, we are not obliged to wait for jackboots before we recognise the direction of travel.

The posters, the uniforms, the slogans are not the whole story, but they are the weather vane. And right now, it is pointing to an ugly wind.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

-1.jpeg?quality=75&width=230&crop=3%3A2%2Csmart&auto=webp)

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks