The popularity of homeschooling is soaring. Should we be worried?

Once seen as niche or eccentric, homeschooling has surged since the pandemic – driven by anxiety, ideology and parents’ desire to reclaim control of education, writes Chloe Combi

Homeschooling got its highest cultural exposure in the 2004 film Mean Girls, when Lindsay Lohan’s Cady Heron gets pulled out of her idyllic homeschooled life in Africa (though we never learn which country) and plonked into the ferocious Darwinism of high school in America.

The film reinforced some of the perception that homeschooled kids and families aren’t normal, either being weird geniuses that a normal school can’t cater for or hyper-religious types unwilling to countenance concepts taught at school like evolution and homosexuality.

In the 20 years that have passed since Mean Girls, homeschooling hasn’t gone mainstream exactly, but it has become exponentially more common in the UK, US and Europe. At the last count in autumn 2024, according to the Department for Education, 111,700 children were being homeschooled in the UK, a significant increase from the 92,000 in October 2023. Going back to 2015, the number was just 37,000.

The UK has the highest number of homeschooled children in Europe, though there have also been sharp rises in Belgium and France. But this is dwarfed by the estimated 3.6 million students being homeschooled in the US, which has also seen a sharp rise in the last half-decade – up from 2.5 million in 2019.

There is no doubt that the record numbers are connected to the long tail of the pandemic when the world’s children were kept home from school for months at a time. This week’s Covid inquiry and grilling of Boris Johnson, the former prime minister, revived debates over the price young people paid to protect the elderly and vulnerable. Johnson admitted children paid “a huge price for others” in their loss of schooling and social and cultural experiences – something many of them continue to pay, with thousands never settling back into a school routine.

According to the DfE, 2.26 per cent of pupils in the UK are severely absent, which means they missed more than half of their classes, which is significantly above the 0.81 per cent 2018-19 pre-pandemic levels. A staggering 1.28 million children and teens (roughly 17.9 per cent of the school population) are persistently absent, which means they miss 10 per cent of their school sessions.

While most parents and carers were delighted to see the end of lockdowns and to send their children back to school, for some the pandemic signalled an alternative path. Shirley, 50, noticed her two young teen daughters were exponentially happier not attending school, with one daughter, Ella, who was then 14, seeing a dramatic improvement in an eating disorder she’d suffered from on and off before the pandemic.

The most common reason is low confidence in schools and the traditional education system, combined with increasing concerns over issues like big class sizes, safety at school, and an inability to cater to the specific and individual needs of every child

Shirley and her partner arranged to homeschool both her children up to GCSEs. She explains: “My girls absolutely blossomed during lockdown, they started playing, reading, laughing, listening to music and Ella started eating properly again. It was like having my kids back again, and I realised how much school had been dragging them both down with endless girl dramas, fights and upsets.

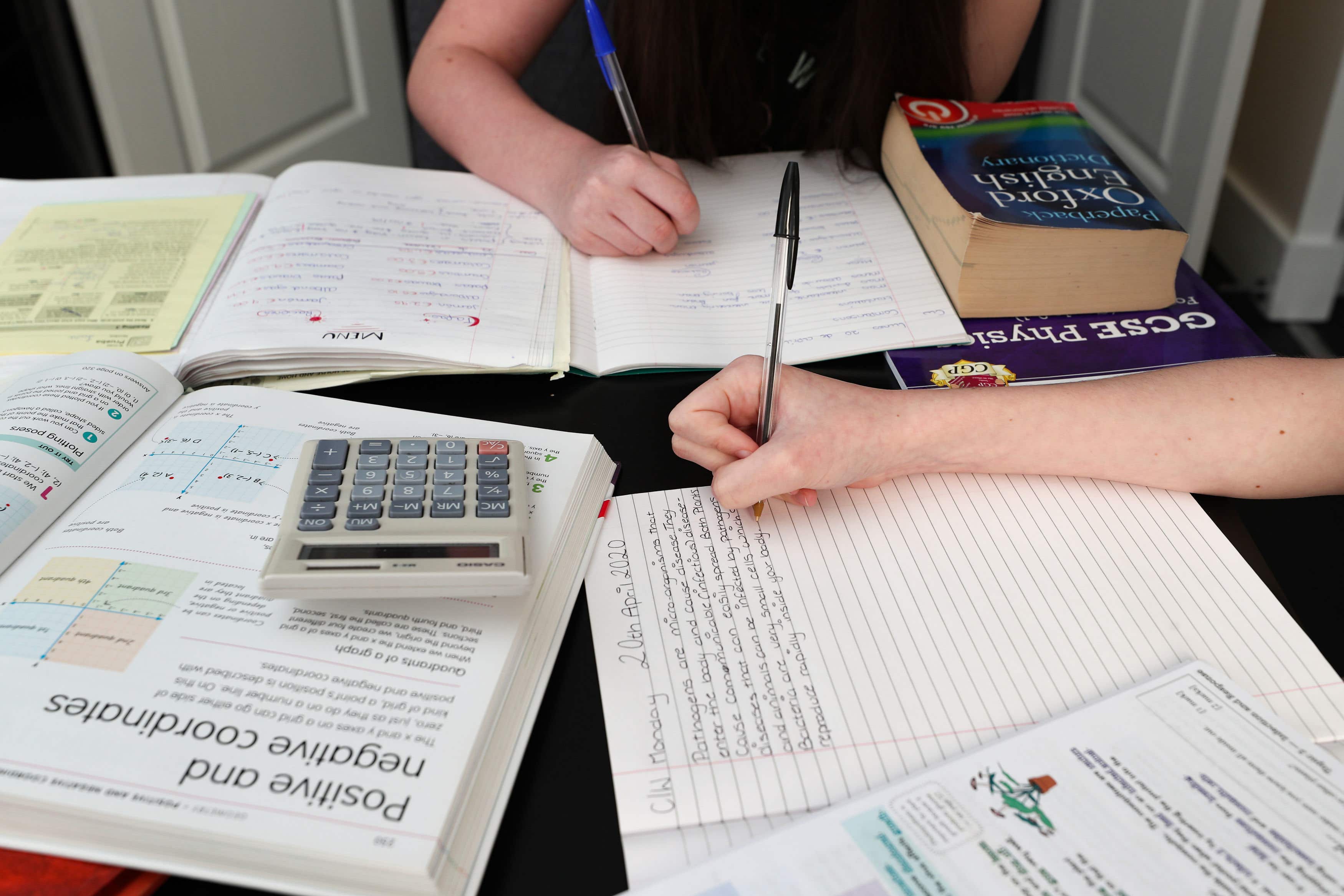

“They were both so upset at the thought of going back to school, we decided to teach them their final GCSE years with the help of some tutors. They both excelled and I think it was a lifesaving decision for all of us, but it was bloody hard work and expensive. We had to take out a loan to pay for the tutors.”

However, the pandemic is not the only reason homeschooling has continued to reach record highs in many countries. The reasons behind families deciding not to send their children to school are varied, but there are factors that come up in most of the families I spoke with.

The most common reason is low confidence in schools and the traditional education system, combined with increasing concerns over issues like big class sizes, safety at school, and an inability to cater to the specific and individual needs of every child. Greater awareness and diagnosis of special educational needs has put further pressure on schools at a time when they have fewer resources than ever to cater for them.

Kayla, 41, has two children, Bertie, seven, and Hattie, 10. Kayla made the decision to homeschool her children a year ago and has given up her job as a speech therapist and adapted their dining room into a full-time classroom they share with another homeschooling family.

“Bertie has special needs, having been diagnosed with severe ADHD, and Hattie is incredibly bright with a specific gift for music,” Kayla says. “Every day, school increasingly just wasn’t possible for Bertie; he was either getting into trouble or freaking out every morning, and Hattie was just getting lost in her class and was completely withdrawing.

“We couldn’t afford to send them both to private school, so after nearly two years of researching, preparing, reading endless books and taking some classes myself, and getting involved with an online homeschooling community who’ve been a lifeline – I share teaching with one parent – Hattie and Bertie are fully homeschooled and I believe doing much better than they would in school.”

Kayla is clear about the huge commitment homeschooling is and how, if you want it to be successful, it requires someone who can do it full-time with serious knowledge about teaching and a vision for what you want your child to learn. And then there’s the social aspect. Most parents and homeschooled children say the biggest prejudice they encounter is the assumption that their kids will be isolated and cut off from essential childhood and teenage cultural and social experiences.

Homeschooling families overcome this by developing communities – some virtual and some real-life – as well as using charities and other organisations that facilitate meetups, support and social opportunities.

But the different generational needs can be hard to navigate. Many of the children and teens I spoke to hugely enjoy the homeschooling experience and the different education and lifestyle it gives them to their “schooled” peers. But some, particularly when they reach teenage years, miss the excitement and buzzy diversity of school.

Charlotte*, 15, has been homeschooled since she was nine, and her demands in the last two years to go back to school have caused real friction with her parents, who are fully committed to the project of educating her and her two younger sisters. “I stayed friends with some of my primary school friends and I belong to a swimming team,” she says. “I hear about their school days and even though they tell me I’m lucky to avoid all the stresses of school, I miss it. We have a group of homeschooled families we see all the time, and I know it sounds horrible, but I’m bored of them and just want to see my other friends who seem different.

“Getting a phone made it even worse. You see the Snaps and the texts, about crazy, funny things at school and even the arguments, and I just want to go. The worst is at Halloween and Christmas. There’s a play and discos and people dress up. I feel like I’m missing out because of my parents’ beliefs.”

In America, 75 per cent of homeschooling families cite “moral instruction” and 53 per cent “religious instruction” as driving factors to keep their children at home, believing mainstream schools fail to provide either. In the UK, the predominant factor tends to be educational, but there is a growing anti-government and moralistic sentiment that looks likely to further increase homeschooling rates.

In our hyper-partisan times, with increasing influence of online discourse, growing numbers of people believe schools have a specific political and cultural agenda that they don’t want to influence their children. Some believe schools and universities are too “woke”, with others believing schools – particularly those in inner cities – are too preoccupied with multiculturalism.

At the same time, some families from strict religious backgrounds of all faiths believe their children are exposed to immorality and insufficient religious instruction or space to pray. A parental resistance to their children getting vaccinated is also a growing reason to keep children from mainstream schooling, more in the US. With those elements comes concern for child welfare – that religious, ideological or political beliefs are outweighing what is best for children’s personal development or educational outcomes.

Indeed, the murder of 10-year-old Sara Sharif, who was removed from school after teachers raised safeguarding concerns, has increased pressure on the government to introduce registers of children not in school and give local authorities more oversight on families that homeschool, much to the opposition of many of the families.

Amanda Grimberg, the executive director of the Coalition for for Responsible Home Education in the US, voices a note of concern about the closed ranks nature of homeschooling education that can be both evident in the US and in the UK.

“The majority of home-schooling parents have their children's best intentions in mind,” she says, but she calls for an agreed homeschooling policy to stop more serious problems. “On the more severe end of the spectrum, children are physically abused and neglected,” she says.

Margaret, 73, successfully homeschooled her three children, who are now grown up and have careers and families of their own. She is discussing the possibility of helping her middle daughter homeschool her primary school-age grandchildren – believing children do better outside of the constraints of traditional school.

There’s little play, no creativity, no interacting with nature and they start getting tested and organised into academic value aged six – it’s not a wonder kids and teens are sick, stressed and struggling with life

“Children are overtested, overstressed, and underdeveloped in every way in schools and it’s gotten much worse since my children were at school,” she says. “There’s little play, no creativity, no interacting with nature and they start getting tested and organised into academic value aged six – it’s not a wonder kids and teens are sick, stressed and struggling with life.”

Margaret describes her beliefs and politics as “very leftie and now quite anti-government, as I don’t think the government has people’s best interest at heart, especially young people”.

There is a growing “anti-school” movement online that sometimes goes under the hashtag #unschooled, led by young people who believe schools are bad for their mental health, failing to teach the right skills, and are hotbeds of bullying and social exclusion. Emerging from this are many high-profile parent and teen influencers who extol the benefits of homeschooled life, such as Katie Klein and Lindsay and Derek Lane, who frequently share “inspirational” posts of their kids who don’t attend school.

However, homeschooling is not an inspirational Instagram page. It’s a serious undertaking and one that demands commitment, time and a parent to cross over the boundary from caregiver to teacher, which can fundamentally alter and challenge relationships.

Families considering it are encouraged to do serious research and ask themselves whether they are prepared to take on the responsibility of shaping their child’s knowledge as well as their happiness and wellbeing.

* This name has been changed to protect the child’s anonymity

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks