The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

‘You don’t need to obsess over protein and calories’: Joe Wicks on beating the UPF trap and decomplicating food

Protein bars might be booming, but Joe Wicks argues the real fix for our UPF-fuelled snacking culture is far simpler: cook more. Hannah Twiggs breaks down why he says we don’t need to obsess over macros – just meals

There was a time, not so long ago, when Joe Wicks belonged to the nation. He was in living rooms at 9am, barking burpees at children while frazzled parents tried to remember how to lunge. “The nation’s PE teacher,” they called him, and the name stuck.

“I haven’t heard that for ages,” he laughs, speaking to my colleague Emilie Lavinia on the The Independent’s Well Enough podcast. “It’s been a while… six years ago, in lockdown.” He insisted he never crowned himself, but for all the humility, he’s fond of the title. “It’s the proudest thing I’ve achieved.”

Post-pandemic, Wicks has been busy. The Body Coach app, children’s books, a Channel 4 documentary, a small army of followers trying to sculpt abs in the morning before the school run, and now a cookbook called Protein in 15. Given the moment – the “protein era”, if we must – the timing is exquisite.

Supermarket shelves are groaning with high-protein everything. Bars, crisps, puddings, yoghurts, popcorn, bagels, ice cream, cereals, brownies, pizzas. If you can eat it, someone, somewhere, has added whey and slapped “25g!” on the front of the packet.

Wicks, though, did not write a love letter to protein pudding. Protein in 15 is about, as he puts it, “trying to get people cooking again”.

“You’ve got this snacking culture where people believe, ‘as long as I'm having a protein bar or a protein yoghurt or a protein bagel, protein crisps, I'm eating healthy’,” he says. “And some of those items may be healthy, but a lot of them are just masking the fact that they are full of additives and emulsifiers, gums and sweeteners and artificial things that aren't really gonna be good for your overall health.”

“The only solution from all the research and the documentary I did and going to talks and reading loads of books around ultra-processed food is cooking more,” he says. “Because then you are in control of your calorie intake and your salt, fat and sugar, but also your energy and your mood and your mental health.”

It is not the glamorous answer to the ultra-processed foods (UPF) crisis, but it is the only one he finds credible. Cooking gives you control. Control gives you stability. Stability stops the cravings. Protein bars are merely the nicotine patches of snack culture.

Wicks is not evangelical about what you cook, only that you do. “I’m a big fan of batch cooking,” he says. “Make a big curry or bolognese or chilli, or a veggie pasta bake.” Leftovers are currency. They stop you from “grabbing that meal deal or that takeaway on the way home”.

Part of the criticism Wicks faces is economic: who can afford to cook from scratch in 2026? Who can afford lean meats, fresh vegetables and time?

He doesn’t dismiss this. He’s lived it.

“It’s a really difficult thing to talk about because you want to give advice and for some people, unfortunately, they are forced into eating these foods at a high volume,” he says. “I was one of those kids. I grew up on benefits and we had a really unhealthy diet. My mum wasn’t educated in cooking, so I’d say my diet was 80-90 per cent ultra-processed food.”

He’s keen to destroy the idea that healthy cooking equals expensive cooking. “Of course you’re not going to be able to afford lovely chicken breasts and beef mince in all your recipes,” he says, “but you can use alternatives. There’s tins of vegetables and frozen veg … you can add lentils to a really nice veggie bolognese.”

The real expense, he argues, is the daily drip-feed of convenience foods. Most of the recipes in his book cost “only two quid per portion”, which “people are probably [spending] on a meal deal or a sandwich every day,” he says. “Even protein bars are like, what, three or four quid? They’re not cheap.”

His preferred model is depressingly reasonable: “If you get a little bit more organised and sit down on a weekend and plan your meals and do an online shop like I do, I do think you could be better off financially.”

It’s hardly sexy, but it’s hard to argue with.

“With this book, I’ve tried to take that philosophy around quick, healthy food – which I’ve been doing for 10 years now, since Lean in 15 and all those books – and really focus on protein.” he says. He isn’t against high-protein eating. Far from it. He just wants to remove the neuroticism from the process.

“I’m from the school of thought that I don’t think you need to be too obsessed about daily calories, daily protein targets,” he says. “I’ve always been much more about balance and a bit more flexibility.”

I’m just here trying to help consumers get the truth around the ingredients and give people a chance to make an informed decision and eat healthier. That’s really my only goal in life

This is Wicks 2.0: less six-pack, more saucepan. Still protein, sure, but protein as a food group, not a lifestyle product. The distinction matters more than you think.

Protein’s cultural image used to be simple: boys in vests swigging shakes after bench press. Not anymore. Protein is now for everyone, including people who have never used the word “hypertrophy”. TikTok is an endless scroll of “protein oats”, “protein popcorn”, “protein pancakes”. There’s even whey in instant noodles, now.

Wicks doesn’t hate it, exactly. He just refuses to talk about protein the way fitness influencers do: with whiteboards, bodyweight-multiplying and wild-eyed macros spreadsheets.

“You need to be eating it,” he admits, “but not obsessing over 40 grams per meal. It doesn’t have to be that complicated. Some days you’re going to have more, other days you’re going to have a little bit less. It’s more about trying to be conscious of it.”

When asked what protein is actually for, he sidesteps the usual gym-bro catechism. Yes, it matters for “muscle” and “repair recovery”, but he also points to “hormones in the body”, “skin, hair, nails”, “good gut health and digestion”, “perimenopause”, “focus and concentration”, and the practical bit: “It keeps you fuller for longer.”

In other words, protein is not just for men who lift things up and put them down again, repeat. It’s for women in perimenopause, teenagers glued to their phones and anyone who finds themselves elbow-deep in the office biscuit jar at 3pm. It is also, Wicks argues, one of the few ingredients that can meaningfully reduce the sort of absent-minded snacking that ruins everyone’s good intentions.

Which brings us to the supermarket problem.

There are few things Britain loves more than a health shortcut, preferably one that can be eaten on the bus. Protein bars were inevitable. They promise virtue but deliver confectionery. They look sporty but they behave like Mars bars in expensive gym kit.

Wicks has seen the industry pivot to meet the boom. “There’s not just one fitness influencer. Now, there’s millions of people and they’re always emphasising the importance of protein,” he says. Brands, forever pragmatic, responded by taking isolate or whey and “sticking it into every single food item on the shelf”.

It works because the protein halo is powerful. But it’s also misleading.

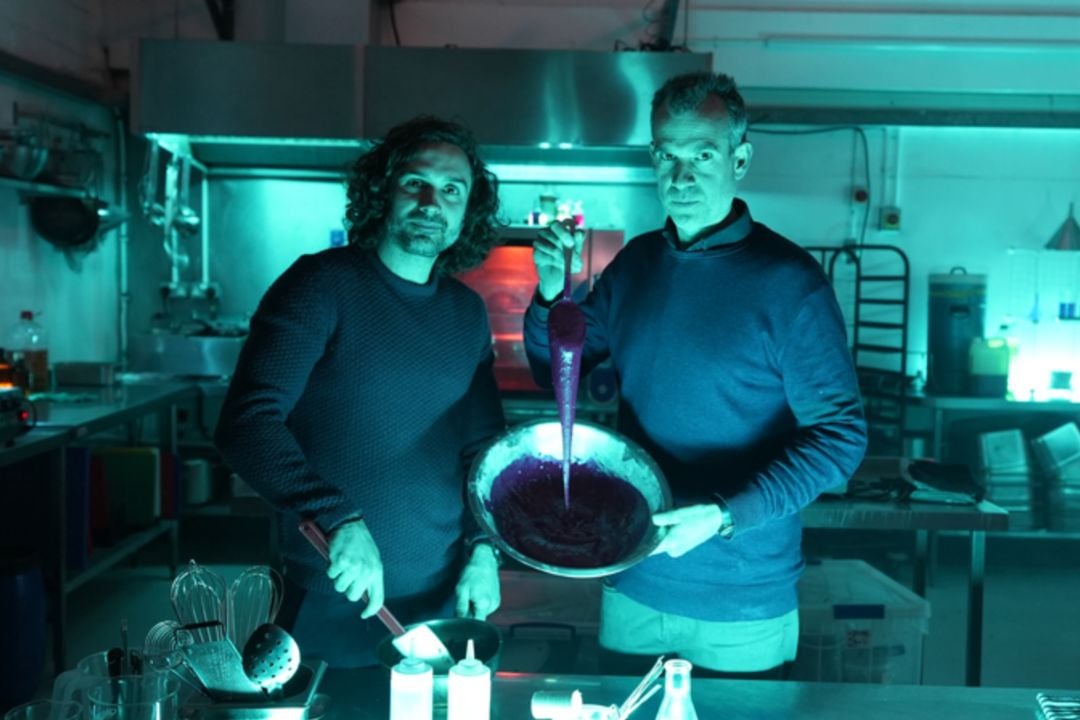

Wicks knows this well, after he fell down the rabbit hole last year while making Joe Wicks: License to Kill for Channel 4, in which he investigated the growth of UPFs, the gaps in labelling and the marketing tactics that hide unpronounceable ingredients behind cartoonish packaging. The title alone tells you it wasn’t going to be a cosy hour of grocery shopping.

The most memorable sequence involved a protein bar with two faces. “On one side, it said 30 grams of protein, 200 vitamins and minerals and all these health claims,” he explains. “But when you turned it over, it’s the deathly protein bar. It said, ‘may increase the risk of stroke, dementia… and cancer” – health risks that researchers have linked to high consumption of UPFs.

If you’ve ever wondered whether fitness television can still provoke, the answer is yes. The real surprise was who got angry.

“I was really surprised at the amount of anger and pushback from the fitness community,” says Wicks. “It was other fitness coaches and dieticians and nutritionists really pushing back with the narrative of: you are demonising foods, you are stigmatising low-income families, you are promoting eating disorders.”

Wicks was blindsided. “I’m so used to getting such positive responses to everything I do that I wasn’t ready for it,” he says. “It knocked my confidence a little bit.”

But he doesn’t regret it. “I’m just here trying to help consumers get the truth around the ingredients and give people a chance to make an informed decision and eat healthier. That’s really my only goal in life.” And sometimes, he says, “you need to do things a little bit provocative” because “it is scary s**t”.

He is also, as he keeps reminding us, not interested in telling anyone they’re failing. “My biggest concern is, with anything I do, I never want to upset anybody,” he says. “I’m such an empath and I really care about people.”

One of Wicks’ strongest arguments for protein has nothing to do with muscle at all. It’s about how food makes us feel – and how UPFs make us feel bad.

“We always think of exercise for our mental health, but I really believe that food fundamentally changes how we feel,” he says. “If I’m having a bad day of eating and I’m eating a lot of junk and UPFs and chocolates and sweets, I instantly feel it in my mood. I depress and I feel low and I crave it every day.”

Anyone who has eaten an entire share bag of chocolate buttons in a moment of emotional weakness knows this cycle well. It is not a character flaw. It is a feedback loop. And in Wicks’ view, no amount of protein pudding will fix it.

Strip away the burpees and the pandemic nostalgia and you find that Wicks is offering something deceptively radical: literacy. Not wellness optimisation or macros perfection, but literacy: ingredient literacy, cooking literacy, child-feeding literacy.

Protein is merely the delivery system. It fills you up, steadies blood sugar, stops the grazing, protects mood and hormones and, crucially, forces you to make actual meals. It’s hard to hit 25g of protein by eating crisps; it’s easy if you fry some eggs or make a bolognese.

It is also quietly subversive in a world where every health solution is sold in single units at £2.99 a shot.

Somewhere between lockdown PE and License to Kill, Wicks stopped being a workout influencer and became something closer to a kitchen coach. Less glam, more useful. Less dopamine, more fibre.

“I want to empower people and make someone feel like they can make a change for themselves,” he says. And in a wellness landscape obsessed with perfection, that might be the most radical message of all.

Listen to the full episode of Well Enough with Joe Wicks on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks