Why Roy Keane has embraced his role as the angriest man in sport

As new movie ‘Saipan’ tells the tale of Ireland captain Roy Keane’s furious row with manager Mick McCarthy and subsequent walkout from the World Cup in 2002, Jim White asks why the former footballer and now equally implacable pundit remains such a compelling figure

There was a moment on Sunday that spoke loud and clear about Roy Keane’s standing in the world. It happened in a London cinema at a special screening of Saipan, the new movie dramatising Keane’s infamous walkout from the Irish football squad ahead of the 2002 World Cup. After it had finished, a Q&A session was staged, featuring the film’s directors, husband and wife Glenn Leyburn and Lisa Barros D’Sa, alongside its two stars, Eanna Hardwicke, who is quite magnificent as Keane, and Steve Coogan, who deftly characterises his adversary, Mick McCarthy. The quartet were being quizzed about the project’s backstory, and the question on everyone’s mind was asked: what was the man himself’s involvement? Had Roy Keane given it his blessing? Indeed, had they ever considered inviting him on board as an executive producer?

“Oh my God,” said Leburn, the tremor audible in his voice. “The thought of having Roy Keane on set.”

There was no need for him to elucidate. A mumble of recognition spread through the cinema as everyone pictured Keane in his Methuselah beard, standing at the side of the studio as the camera rolled, a look of disdain spreading across his features as he hears the director tell Hardwicke that the latest take was absolutely spot on.

“Why are you getting so excited about what he’s just done?” you could almost hear Keane sighing. “It’s his job.”

It turns out, beyond receiving a formal letter from the producers informing him it was happening, Keane has nothing to do with the film. In truth, you can understand their reluctance to have him involved. Because there can be no public figure in contemporary life with an image as terrifying as the one Keane maintains. As he sits in judgement on football, either for Sky or as an increasingly popular podcast presence, he appears to be a man ever on the brink of ferocity. His pronouncements, delivered with a stare of such glowering intensity it could stop a tank in its tracks, are almost invariably curt, dismissive, laced with disappointment. Those around him – his fellow pundits, the presenters seeking his opinion – appear continually alert, as if checking for the exit doors. This is broadcasting’s biggest bear, his appeal built on the possibility that at any moment he might be poked into rage.

And the thing is, as we watch, we have convinced ourselves it is no act. This is not the usual gob-for-hire member of the pundit class, happy to criticise for clicks. Everything we have seen and heard in the past insists the anger waiting to erupt from within Keane is for real. Very real. He is a man, we believe, who feels what he says.

Such authenticity is central to his appeal. This was, after all, a footballer for whom the very thought of compromise was anathema. I remember once watching him play for Manchester United and, in one of the moments when the Old Trafford crowd fell silent, hearing him unleash a lengthy tirade of ear-melting ferocity at one of his teammates. Funnily enough, given how the two are these days regular podcast colleagues, chatting about the modern game over coffee and croissants, it was Gary Neville on the receiving end of his verbal Exocet. And as the fan who berated him from the crowd at Ipswich Town when he was conducting his Sky duties on the touchline ahead of a game a couple of years ago found out, even long into retirement, he remains someone never shy of backing himself up physically.

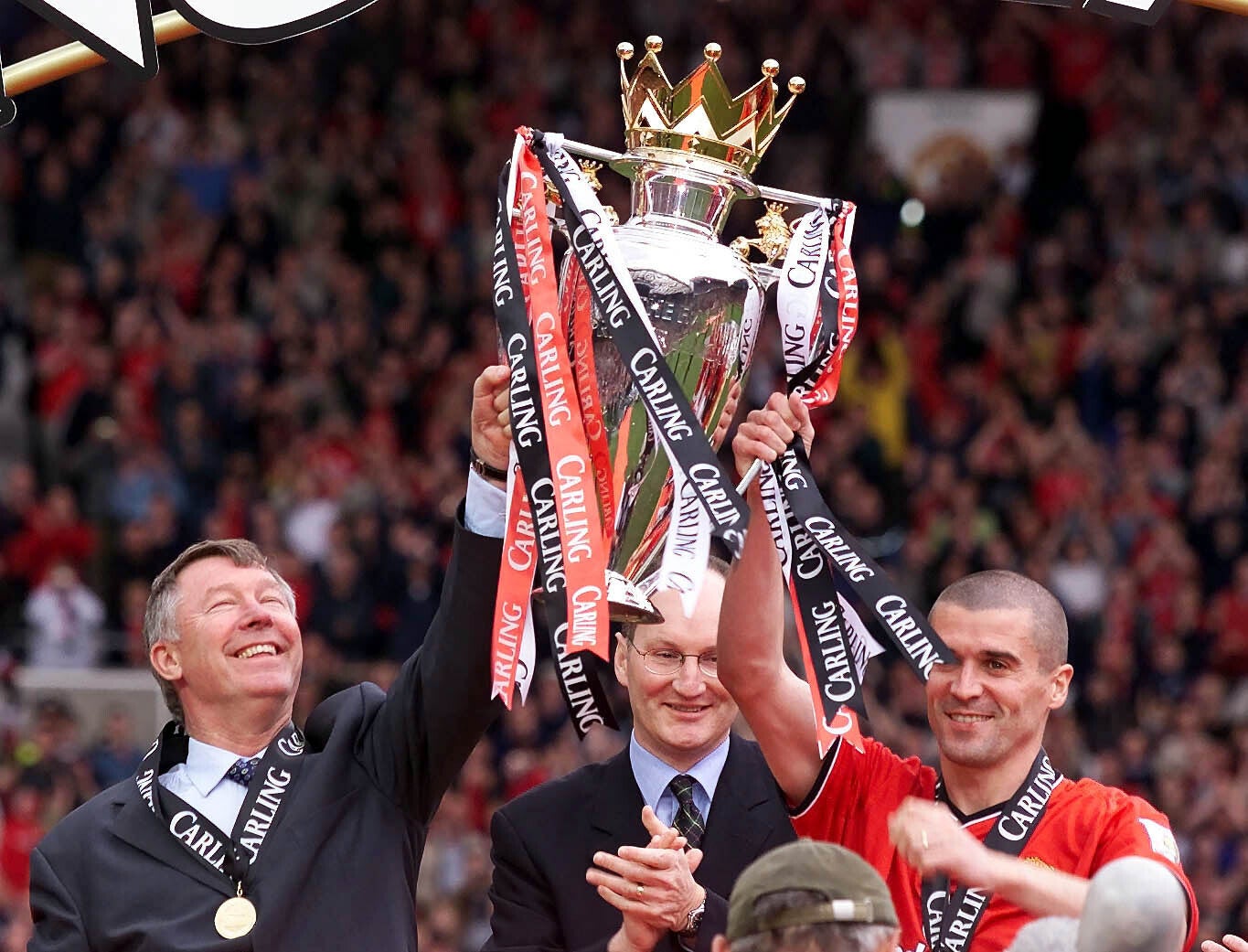

“I wouldn’t argue with him,” Sir Alex Ferguson, his manager at United, said of Keane at the height of his playing prowess as the finest enforcer in world football. “Have you seen the size of his forearms?”

Not that Ferguson followed his own advice. The two later fell out spectacularly, a row which is clearly still recorded in Keane’s mental black book, as he recently dismissed the man he used to call Boss as “hanging around Manchester United like a bad smell”.

And Saipan, which is released in cinemas this week, will only enhance his reputation as one of society’s angriest men. It tells of the volcanic personality clash between Keane and McCarthy. These two are approaching the World Cup from very different positions: one laser-focused, intense, determined, the other apparently happy just to be there, enjoying the moment. Almost from the film’s opening shot, we discover that Keane is more than a little dismayed by the lack of proper preparation that he believes stymies the pre-World Cup camp on the American island in the middle of the Pacific. He sees it as an affront. He wants his country to approach the tournament as other countries will, with a professional determination to win. McCarthy prefers to treat the time as a bonding exercise, an opportunity to relax after a long, hard season, more conga lines than circuit training.

“Not everyone is Roy Keane,” he says of a group who share little of their captain’s fervency.

The gap between the two is taken by the film to represent something wider: the fissure between an Ireland personified by Keane as a society anxious to punch its weight in the wider world, and the old philosophy embraced by McCarthy of “we’re just here for the craic”. After the blistering verbal tirade that forms the dramatic climax of the movie, Keane puts aside any personal ambition of playing in the World Cup and storms home to Manchester. Looking back at it with a 24-year distance, it remains a stand at once both remarkably principled and ultimately self-defeating.

And it was a moment that didn’t just seal his reputation as an angry man. It became one mythologised in the wider Irish consciousness: everyone had an opinion of Keane. For some it confirmed him as the epitome of integrity. But Hardwicke remembers being a five-year-old growing up in Cork at the time, coached by his grandad that if anyone asked his opinion of Roy Keane, it was that he had let his country down.

“He is a force of nature,” added Coogan. “Like a storm ready to break.”

Well, in truth, not all the time. Away from public scrutiny, there is a wry self-awareness about Keane. In private, a warm and loyal family man, he is a superb anecdotalist, his stories delivered with a comic’s timing. And a friend of mine, who walks his dog in the same stretch of Cheshire countryside that Keane took to in the aftermath of his departure from the World Cup, says he is still out there, every morning. The locals exercising their mutts, he adds, are united in terror at the thought of their pet misbehaving in front of Keane’s beautifully trained dog. But the reality is more nuanced. When Keane bumped into my friend exercising his new puppy, he stopped and chatted knowledgeably about the breed and its shortcomings. He was full of charm. Though ultimately, there was still a distance to be maintained. The next time they coincided on the walk, my friend issued a cheery “hello Roy, good to see you”. It was met with a dismissive roll of the eyes.

And that is the point about the cult of Keane: he is more than cognisant of his reputation. Indeed, in his broadcasting life, he plays it like a musical instrument, perfectly attuned to the meme potency of a sideways sneer. It is a lucrative ability, too, making him the most in-demand pundit on the circuit, the one whose output we all love to scroll. No wonder advertisers queue around the block to cast him in their commercials.

For McCarthy, the post-football, post-Saipan world has proven far less of a money-spinner. He has, albeit without the same ubiquity as his nemesis, joined the podcasting circuit. Sadly for his listening figures, you suspect that any invitation to Keane to join him on The Managers, the podcast he does with Tony Pulis, would be received with the same terse dismissiveness as we see at the conclusion of the movie, when Coogan as McCarthy makes a final, forlorn phone call to try and persuade his captain to return to play in the World Cup.

“I take it that if I asked you back the answer would be no,” says McCarthy.

“Yes,” comes the reply.

“You mean: yes, it’s a no?”

“Yes, it’s a no.”

The cult of Keane summed up in a sentence.

Saipan is on general release from 23 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks