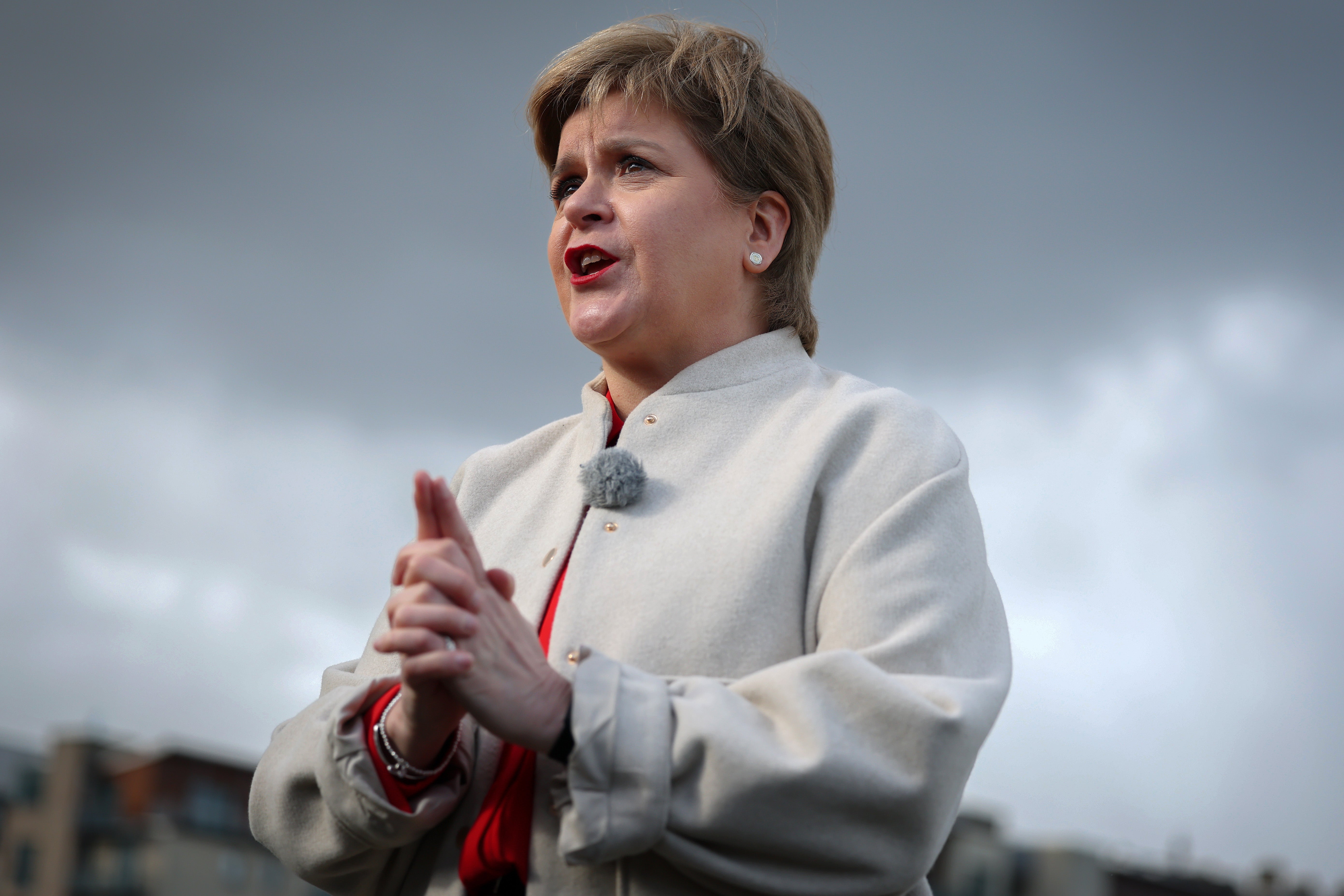

Nicola Sturgeon’s Frankly memoir is an act of vanity that leaves too much unanswered

From her midlife ‘breakdown’ to the rumours around her relationships and sexuality, Nicola Sturgeon’s memoir doesn’t lack for personal revelations. But when it comes to SNP scandals and Covid care home deaths, her account feels less like honesty and more like careful self-preservation, writes Andrew Nicoll

In the preface to her book, Frankly, former Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon says she has tried to avoid “the vanity and self-justification that so often characterise political memoirs”. I know exactly what she had in mind. Ten years ago, I had to read and review Alex Salmond’s book, The Dream Shall Never Die. It’s probably the worst political memoir ever written: shallow, self-serving, exculpatory mush. Sturgeon’s Frankly is a lot better, but falls well short of her high ideals – and for those of us who followed her 30-year political career, it leaves an awful lot of questions unanswered.

First, it’s important to say that Sturgeon undoubtedly authored this book without the assistance of ghostwriters. Having known and worked with Sturgeon since 1992, I recognise her voice, and the editors have not bothered to correct her signature grammatical errors.

The book contains the perfect mix of bombshell revelations, astonishing, unprovable smears and tearful personal reminiscences required for any publisher hoping to make their colossal £300,000 advance back. For example, Sturgeon reveals that she was so broken by the Covid crisis and the subsequent public inquiry that she ended up in therapy, unable to control crying fits that would suddenly overwhelm her.

After breaking down in the witness stand, Sturgeon said: “The inquiry became the straw that almost broke the camel’s back. I could barely function. I cried, on and off, for days.”

She sought professional help and went through a period of counselling. “I have never felt so utterly adrift from any rational sense of who I am, or so completely unable to find any lightness in life,” she writes.

Her sudden, unexplained resignation as first minister – just days after saying that she had “plenty more in the tank” – came not because of the police investigation into SNP finances, but simply because of exhaustion and the realisation that she had become too polarising a figure.

She adds, “Lastly, there was a personal midlife assessment at play. I had been struggling with menopause symptoms for a while. One of my deepest anxieties was that I would suddenly forget my words midway through an answer at First Minister’s Questions. My heart would race whenever I was on my feet in the chamber, which was debilitating and stressful.”

But the revelation that will set the tabloids ablaze is Sturgeon’s decision to address the troubled question of her own sexuality. It has been the subject of gossip and tittle-tattle for years, right up to the bizarre internet rumour that she had set up a lesbian love nest near Stirling with the former French ambassador.

Sturgeon laughs that off, only to reveal: “Long-term relationships with men have accounted for more than 30 years of my life, but I have never considered sexuality, my own included, to be binary.” She wants to “reclaim a private life, to no longer feel that who I am in a relationship with is anyone’s business other than my own”.

At its heart, Frankly is the everyday story of an ordinary working-class girl who learns to dance in the rain after rising from a council house in Ayrshire to bestride the world like a political colossus and star in a Vogue photo shoot – all while constantly battling men. Misogyny gets 16 listings in the index. Boris Johnson gets 10.

But Frankly is driven by the very flaws – the vanity and self-justification – that Sturgeon said she wanted to avoid. They are unavoidable. They are baked in. Any political memoir is an act of vanity committed by someone who thinks the rest of us care about what they think. As for self-justification, she knows there are topics that can’t be avoided: the SNP finances scandal, her handling of the Covid crisis and the Alex Salmond controversy. What she has to say about those is, in my view, oftentimes less frank than the title of her book would demand.

Sturgeon is open about her personal anguish over Salmond. Her predecessor as first minister was her friend as well as her mentor for two decades and, she says, she still wakes from dreams thinking they have been reconciled. But it’s clear that, long before the split prompted by the sex allegations against him, Sturgeon had started to fall out of love with Salmond.

According to Sturgeon, Salmond “hardly engaged” with the independence white paper prepared ahead of the 2014 referendum. Salmond pushed the financial assessments of government economists “to the outer edges of credibility”, and she “gave up on him” when he decided to take a week-long trip to China just days before the document launched, making a drunken phone call to her office from Hong Kong’s Happy Valley racecourse.

Sturgeon is unapologetic about her role in the internal Scottish government inquiry into sex assault allegations against Salmond.

Salmond went to the Court of Session over the probe and won £500,000 in damages but, according to Sturgeon, that was simply because of “a procedural error”. The court said the investigation was “unlawful”, “unfair” and “tainted”. That’s quite some error.

Now that Salmond is dead, Sturgeon is free to say what she wants about him – and she doesn’t hold back. She blames him for leaking details of the inquiry to the press in a “gambler’s” tactic designed to take the heat off. Until now, suspicion has hovered over a close Sturgeon aide seen in the Holyrood bar in hushed conversation with the journalist who broke the story. They must be relieved.

Sturgeon also recalls that, in the inquiry into the whole fiasco: “I was cleared by an independent process of … misleading parliament.” In fact, the Hamilton report of March 2021 said only that her “incomplete narrative of events … while likely to be greeted with suspicion, even scepticism by some, is not impossible.” “Not impossible” isn’t quite the same thing as “true”.

Sturgeon insists the “conspiracy” against Salmond “was a fabrication, the invention of a man who wasn’t prepared to reflect honestly on his own conduct”.

But it’s fair to note he was cleared of all charges – and evidence he wanted to bring before the Holyrood committee of inquiry was blocked by the Crown Office before it could be published. Anyway, from Sturgeon’s point of view, the whole mess had nothing to do with her – and she is equally forgiving of herself for her role in handling Covid. “Could we have protected people in care homes better than we did?” she asks.

Well, yes, you could. You could have stopped sending hospital patients you knew to be infected into retirement homes, for example. But who could have guessed that unleashing a viral bomb on frail elderly people would have resulted in the culling of thousands?

As for the police investigation into SNP accounts, which saw Sturgeon arrested and her estranged husband, Peter Murrell, charged, the less said about that – the better. Frankly has been timed so the book is on the shelves before Murrell is in the dock, and obviously it would be entirely wrong to comment on anything that might prejudice proceedings.

Sturgeon must long to explain what she thought when a £110,000 campervan suddenly arrived in the driveway of her in-laws’ home; she must ache to say what she said when Murrell found £100,000 lying around to loan to the SNP – but she must remain silent. She recounts the dawn raid when police snatched her husband as she lay in bed, the mounting horror as the SNP treasurer was arrested, and: “At that point, a depth of resilience I didn’t know I had kicked in. The day before attending the police station, I sat and passed the theory section of my driving test.”

It’s bizarre – like her explanation for the £500,000, unwinnable Supreme Court case she brought against the UK government in a bid to stage a second independence referendum. “The judgement was emphatic. I had hoped that the court might surprise us with a positive ruling, but I hadn’t expected it. The clarity we got was the clarity I had anticipated, and it was the clarity I had come to believe was vital.”

Half a million pounds’ worth of kidney machines not bought – but hey-ho, we got clarity.

As Nicola Sturgeon says: “Ultimately, leaders have to lead; to pick a side and then set out the reasons for the choice we have made.” Even if they make up the reasons much, much later. Yes, this one will sell and sell. The same fans who bought Salmond’s book will buy this one. But I doubt they will read it twice.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks