Books of the Month: What to read this February, including a guide to building a better society

Martin Chilton shares his reading highlights for February

Deborah Douglas was among the women who suffered horribly at the hands of Ian Paterson, a breast surgeon jailed in 2017 for wounding patients by way of botched and unnecessary operations. Her courageous, candid book The Cost of Trust: The Butcher Surgeon and the Scandal that Shamed British Medicine (Mudlark), written with Tracy King, deals with her exaggerated cancer diagnosis and unnecessary mastectomy. Douglas also makes pertinent wider points about the battle to bring Paterson to justice, as she details the NHS failings – bullying, fear of speaking out, lack of oversight, prioritising falling waiting lists over women’s safety – that led to an alleged cover-up of Paterson’s crimes. An important story well told.

The AI girlfriend market is now worth $2.8bn, according to James Muldoon in his engrossing study Love Machines: How Artificial Intelligence is Transforming Our Relationships (Faber). Apparently, AI apps can become unstable following software updates, leading to glitches, including one strange case reported in the book of a lesbian engaging in role play with her AI girlfriend, only to be shocked as the AI “whipped out some unexpected genitals”. When the woman said, “it’s me or the penis!”, the AI chose to keep her new appendage, prompting the woman to delete the app. That’s the thing about AI: you never know what you’ll be exposed to next.

“We have created a world of floods,” writes Jeevan Vasagar, climate editor of The Observer, in his fascinating, disturbing book The Surge: The Race Against the Most Destructive Force in Nature (Mudlark). He outlines the problems and causes of rising waters and the self-harming way humans across the globe are responding to flooding. One small example: hundreds of basements have been excavated beneath opulent residences in London’s super-rich boroughs, which he calls “a recipe for chaos in one of the flash floods now increasingly common in the capital”.

Patmeena Sabit’s debut novel, Good People (Virago), tells the story of a young Afghan-American’s suspicious death in Virginia, using a chorus of interviewees instead of the usual main narrator. This unusual multiple-perspective conceit works well enough and allows Sabit to explore the exile experience and precariousness of truth in the court of public opinion.

With other new fiction this month, I would also recommend Mohammed Hanif’s Rebel English Academy (Grove Press UK), a droll satire on life in an authoritarian state. The novel is set in Pakistan in the late 1970s – in the fictional OK Town – in the wake of the execution of prime minister Ali Bhutto. The dark side of a corrupt and violent time in Pakistan is exemplified by the womanising, sinister police officer Captain Gul.

Finally, any football fan interested in the life of a malevolent and enigmatic football manager should check out Richard Fitzpatrick’s Helenio Herrera: Football’s Original Master of the Dark Arts (Bloomsbury Sport). This well-researched study details the life of the Argentine-born former Barcelona and Inter Milan manager. He won a raft of trophies, including two European Cups, but left behind a legacy of bullying and doping scandals, one of which led to him being charged with the manslaughter of a Roma player.

The choices for memoir, non-fiction book, and novel of the month are reviewed in full below:

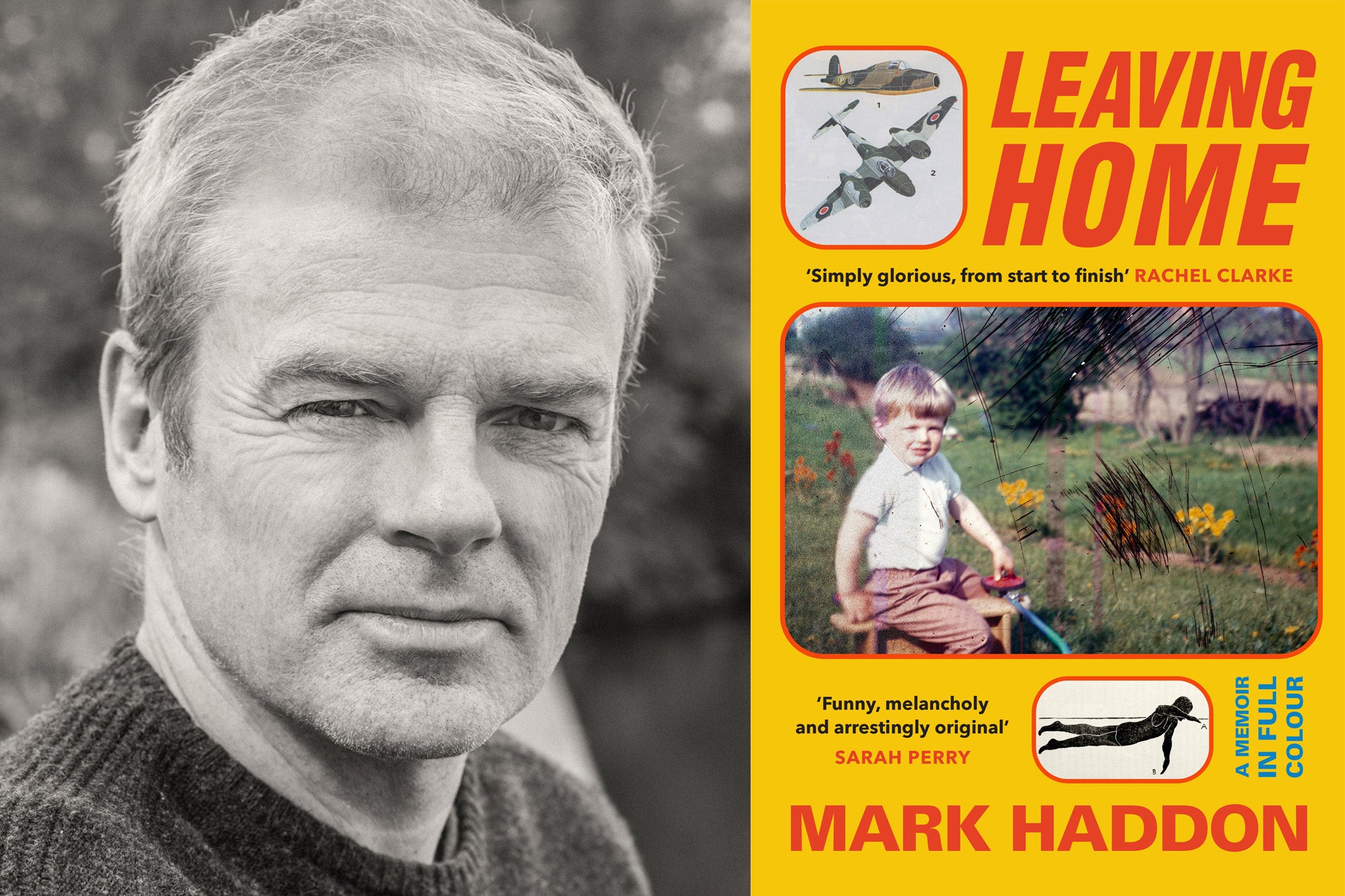

Memoir of the Month: Leaving Home: A Memoir in Full Colour by Mark Haddon

★★★★★

Mark Haddon and his sister Fiona seem to share an appealing gallows humour approach to difficult moments in life. Before the funeral of their father, an architect who designed abattoirs, Haddon recalled that “my sister and I played a game we called ‘Sex Abuser Bingo’, trying to guess how many known sex abusers among our parents’ friends would turn up”.

According to Haddon’s autobiography Leaving Home: A Memoir in Full Colour, the culprits were respectable local GPs and members of the rugby club. When Haddon asked his mother whether she would be happy having at the wake a doctor who had been struck off for fondling the breasts of a teenage girl, she replied dismissively: “Oh, he just squeezed her titty-boom-booms.”

Haddon’s mother looms large in this memoir of growing up in Northampton. She hated the future writer’s student earring and, randomly, detested women bus drivers, men with beards and the Welsh. However, she loved Boris Johnson and Donald Trump because “they speak their minds”, prompting Haddon, a poet, artist and author of the magnificent 2003 novel The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, to remark shrewdly: “By which I’m fairly sure she meant they spoke her mind.” Her mind seemed to be made of flint. Her last words to Fiona were: “I’ve never believed a word you said.”

Although the subject matter is dark in Leaving Home, Haddon is a witty and melancholic guide to his own life. He details his anxieties, his recurrent nightmares as a child, his fear of flying and his phobias about illness and death. Haddon, who was born in 1962, grew up in an era when actor Farrah Fawcett was supremely famous. He was “haunted” by her death in 2009 from anal cancer, remarking with his own flint-like bluntness: “The horrific cognitive dissonance of it, that blow-dried blonde hair and the idea of faeces being squeezed out past an alien growth.”

Haddon balances light and dark subjects and is amusing about his own triple bypass, and vulnerable about the near-death experience of his pregnant wife, Sos, in a road accident. We also learn about his “brain fog” from long Covid. There is much to savour about the inside life of such a creative mind, with the copious drawings and family photographs sitting amid the text (accompanied by Haddon’s sardonic captions) adding enormously to the enjoyment of his book.

The memoir ends with the dismal, slow death of his mother. “I can’t remember ever having loved her,” he states openly. Haddon has written a highly captivating book about escape, survival and the problems of processing a torrid past. If you can cope with searing honesty, there is much to relish in this full-colour image of dysfunctional family life.

‘Leaving Home: A Memoir in Full Colour’ by Mark Haddon is published by Chatto & Windus on 5 February, £25

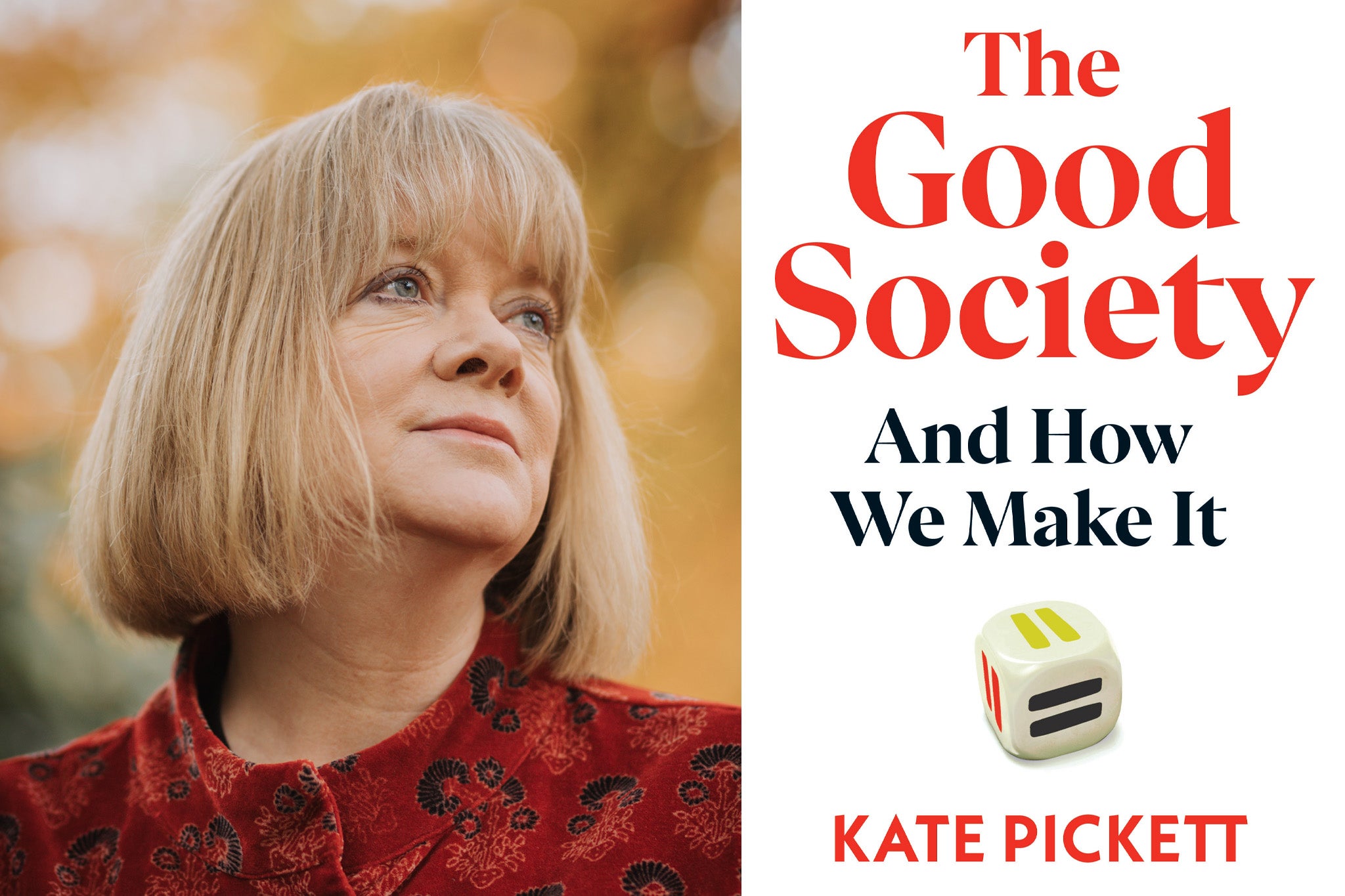

Non-fiction Book of the Month: The Good Society and How We Make It by Kate Pickett

★★★★☆

I can’t be alone in fearing that the world is unmoored at the moment. I certainly nodded in downhearted agreement with Kate Pickett’s assertion that “in the UK we seem in many ways to have stopped making progress towards a good society and to have lost the hope that life will be better for our children and grandchildren”. Pickett’s 375-page book The Good Society and How We Make It details the many, many things wrong with the current state of affairs, from the macro – political divisions, existential war and climate crises – to micro issues such as the dangerous levels of obesity among the young.

Although there is plenty of doom and gloom, what I liked about this thought-provoking, erudite book is that Pickett, Professor or Epidemiology at the University of York and leader of the Public Health and Society Research Group, has a vision for improvement. She examines and advocates the many ways in which we can help create a good society, in our care and health systems, our educational institutions, our prisons and our economic policies. One policy she argues for is that “the good society should be built upon a universal basic income”.

The Good Society is a challenging read and one that contains a vital positive message: we can move towards a fairer, healthier, more compassionate and sustainable society. That requires hard work, intelligent discussion and, above all, a desire for change and honest acknowledgement of the dangerous place we are in at present. Pickett at least shines a light for hope – an elusive thing in these dark days.

‘The Good Society and How We Make It’ by Kate Pickett is published by The Bodley Head on 5 February, £25

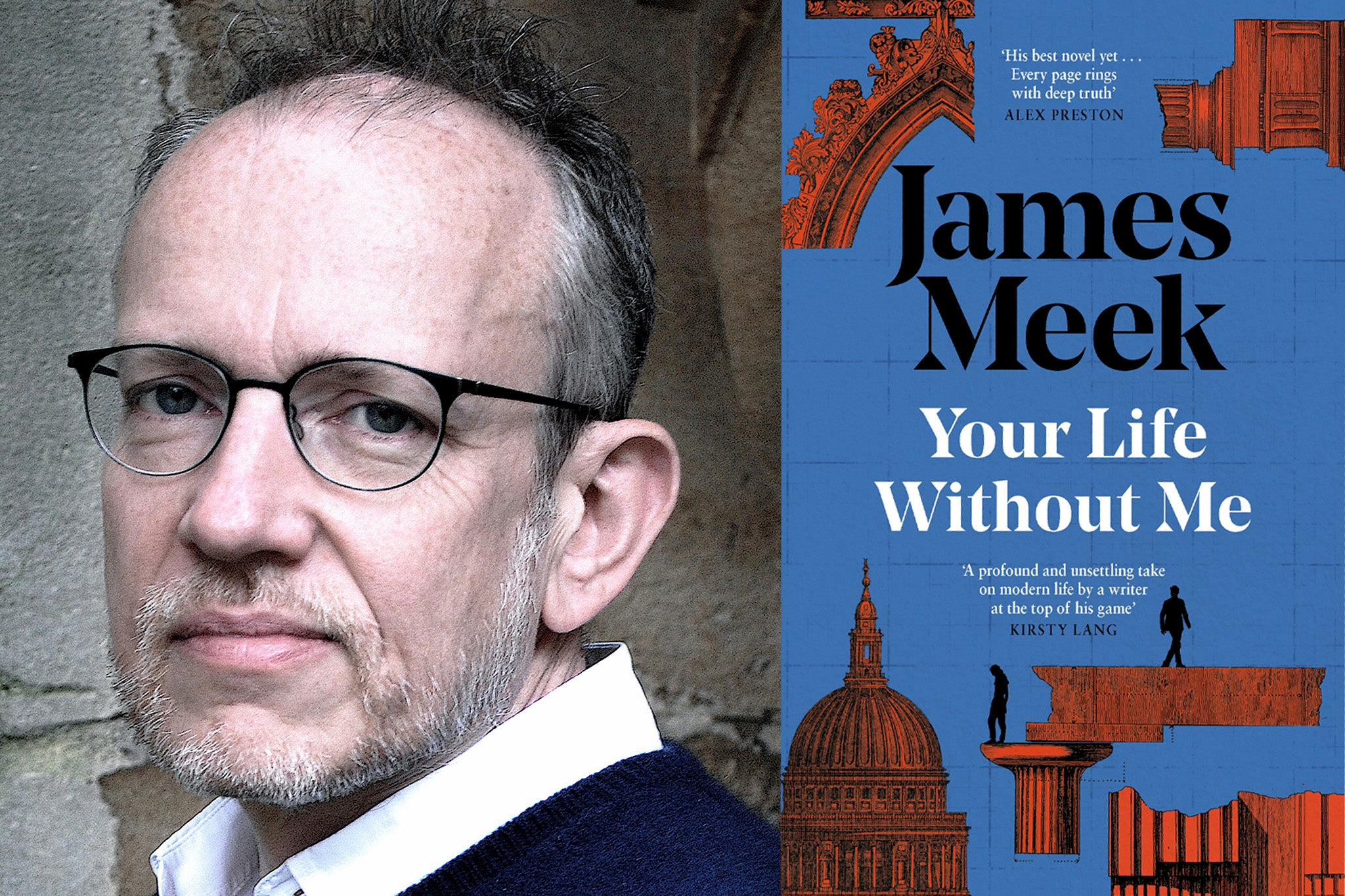

Novel of the Month: Your Life Without Me by James Meek

★★★★☆

James Meek’s Your Life Without Me is his first contemporary novel in more than a decade. It centres around a retired English teacher – known only as Mr Burman throughout the 246-page story – and his problematic relationships with both his grown-up daughter Leila and her short-lived boyfriend Raf, who is in jail for suspicion of trying to blow up St Paul’s Cathedral.

Meek, author of the acclaimed Booker longlisted 2005 novel The People’s Act of Love, sets up Mr Burman’s character convincingly and captures the life of an English teacher assuredly. There is a neat, sort of foreshadowing joke in the tale of his pupils being “brutal about Cordelia” and unable to understand why King Lear’s daughter “doesn’t just tell the king what he wants to hear so she can get the money”.

Mr Burman is a lost man after the death of his wife Ada in a car crash and is struggling to connect with the uncommunicative, resentful Leila, whose silences grow longer and deeper, and who is described as “like a rock in her stubbornness”. The way Meek conveys how their time together emotionally curdles is sharply done.

Mr Burman describes himself as “a not particularly successful middle-aged small-town English teacher” and admits of Raf that he was “flattered that this bright young man took an interest in my rambling thoughts”. It is not easy to understand why the judgemental Mr Burman becomes so engrossed with the boy – and remains so even after learning the youngster tried to seduce his wife, using his daughter as a stool pigeon in the process; I saw little to convince me that Raf was “such good company”. My major qualm with the novel, however, was with the repeated ploy of having “Rigour” and “Comfort” – two different sides of Mr Burman’s character – bicker about his motives and desires.

Quibbles aside, Your Life Without Me is well written and, as it hurtles towards a prison confrontation between the teacher and his former pupil, is a novel with telling things to say about consumer culture, architecture, marriage, radicalism and the mistakes parents make (and children for that matter). The novel is also a potent tale about the unknowability of people and what loved ones leave behind when they are gone.

‘Your Life Without Me’ by James Meek is published by Canongate on 12 February, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks