The untold story of Lowry and why he wasn’t the working-class hero you think he was

Fifty years after Lowry’s death, a landmark documentary brings to light a newly discovered treasure trove of unheard audio tapes recorded with the artist. It explodes a lot of what we thought we knew about him, finds Nick Curtis

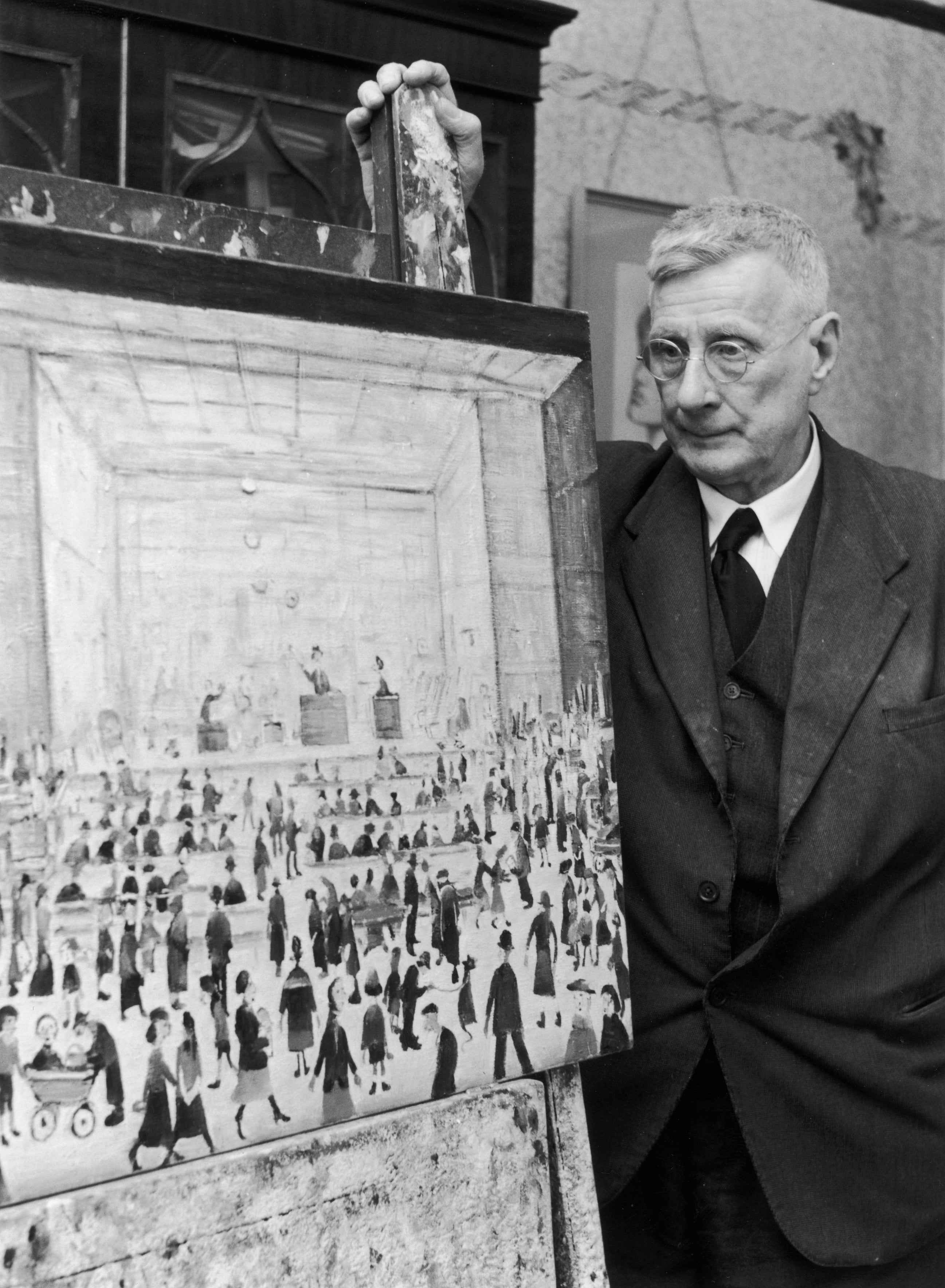

All the little figures. It’s like a disease. You can’t stop it.” These are the words of the painter LS Lowry, discussing the compulsion that led him obsessively to depict the spindly hordes of the industrial working class in early 20th-century Manchester despite decades-long indifference from the art world and his own middle-class family.

They are delivered by Sir Ian McKellen, lip-syncing to long-undiscovered interviews Lowry granted to fan Angela Barrett between 1972 and 1976: an edited recreation of their encounters forms the core of new BBC Two documentary LS Lowry: the Unheard Tapes. The programme unpacks a fascinating and complex story, both of Lowry himself and of UK attitudes to art and heritage.

When he died, shortly after his last recording session with Barrett in his parlour in Mottram in Longdendale and with his reputation at a lifetime high, Laurence Stephen Lowry’s estate was valued at £289,459. In 2022 – coincidentally, the year that Barrett died and her tapes were discovered – his canvas Going to the Match sold for £7.8m to the arts centre in Salford that bears his name, where the churning mills and factories he depicted once stood.

I thought I knew about Lowry: we all think we do. “I don’t suppose there is an adult in the land, who wouldn’t recognise a Lowry at 100 paces,” as TV presenter Robert Robinson puts it in a 1960s archive clip. The hunched, matchstick-legged figures slouching towards their toil; the terraced backyards; the looming chimneys, stark against flat white skies.

But the documentary also shows us early landscapes, still lives and portraits of his parents in oil: eloquent, almost photo-realist sketches; and late seascapes, notable for their lack of human figures and their bleakness. There are two striking self-portraits – one showing a young man of chiselled handsomeness, the other a gaunt, grizzled and red-eyed older Lowry, staring with deranged intent directly from the frame. (The fetish-y “marionette paintings” discovered after his death are not shown.)

.jpeg)

The interviews – plus a roster of art experts and enthusiasts, including novelist Jeanette Winterson and broadcaster Stuart Maconie – explode the idea that Lowry depicted his own milieu, and was driven by a social conscience. Historian Michala Hulme points out he was born into comfort in 1887 in the leafy Manchester suburb of Victoria Park, his father an estate agent’s clerk. The family had a maid and he was privately educated, taking evening classes in art from the age of 18, to the bafflement of his distant parents.

A move among the dark, satanic textile mills of Pendlebury in 1909 initially shocked him (“it was awful… my god, my god”) but then fascinated him. His early oils are indifferent, though his sketches of his mother are sharp and full of character: apparently, she would turn his pictures to the wall when visitors called. His true métier turned out to be the teeming proletarian streets away from his front door. (That said, a later downturn in the family finances showed how tenuous their grasp on gentility was.)

Art historian Leslie Primo says Lowry saw “the extraordinary in the ordinary, people going to work”. Maconie and Winterson agree that he was not a documentary realist but expressed something of the personality of the city and its people, “grandeur and grimness” and a “gleeful truculence”. Artist Tony Heaton praises him as a “blunt speaker” in art and in life, but the superficial openness of his conversation with Barrett masks secrecy and evasiveness.

For all his supposed empathy, his eye was clinical, detached. “There was no political significance in [my art] at all,” he tells Barrett, insisting the workers he depicted were “quite happy” and “accepted their lot”. “I’m not a communist,” he continues. “I’m an out and out conservative.” When Barrett says she’s a socialist, he grumps: “Well, I’ll forgive yer.”

Home from the Pub (1924), a study of three tipsy women, captures their joy but doesn’t share it. The Cripples (1949), shown in the documentary among later studies of the homeless, is a confrontational depiction of figures maimed by war or machinery. Heaton, who uses a wheelchair, loves it.

Most significantly – although he downplayed it, wanting to be thought of as a professional artist – Lowry worked full time as a rent collector for 42 years, toiling at his easel in the evenings and at weekends. His job gave him ample opportunity to observe and sketch the working class but marked him out as a feared figure of authority – an outsider again. Before the war, the art world routinely dismissed him as a “Sunday painter”.

He lived at home with his parents until his father died in 1932 and then his mother in 1939, the year of his first solo exhibition in London, when he was 51. Her death seemed to trigger a breakdown and the first interruption in his relentless artistic output. His subsequent 1940 painting of her empty bedroom exudes despair. During the Blitz he became a fire-watcher, walking the streets as incendiaries fell. “If I got blown to pieces it wasn’t all that [important],” he mutters to Barrett.

Lowry never married. Indeed, he left no record of any romantic entanglements apart from a series of surprisingly modern 1950s portraits of a woman called Ann; possibly a friend of his mother, probably invented or a composite of women he knew. “I never was in love,” he tells Barrett bluntly, before hinting he “might” have married a girl “but she died in an epidemic”. He apparently didn’t lack friends, but one of their surviving number, Simon Marshall, still refers to him on screen as “Mr Lowry”.

The BBC Two show suggests that a postwar need to evaluate Britishness, to define what the years of fighting and struggle were for, marked an upturn in his reputation. Interest in and sales of his paintings increased. He was appointed an official artist for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953 and became a full Royal Academician in 1962.

His work became recognised for his unique style, and as a singular record of a time and place. By which time that era had passed. When he spoke to Barrett, Manchester’s industrial might was in terminal decline and the terraces were demolished in favour of tower blocks, which he despised.

He couldn’t have imagined the prices his works would command today, or the sparkling Lowry gallery erected in his honour. “Someday you may be walking down a street, look into a junkshop window, you’ll see a picture upside down, marked cheap, 30 shillings, and it’ll be mine,” he tells Barrett. “Well,” she replies. “I’ll go in and buy it.”

‘LS Lowry: the Unheard Tapes’ is on BBC Two, 9pm, Wednesday 25 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks