Forget Ulez, Britain must do better than to run away from its eco obligations

Editorial: The UK used to aspire to global climate leadership, and rightly. But now, shaken by soaring fuel bills and inflation, we are turning our backs on the planet

As an exemplar of a good policy badly implemented, the expansion of the ultra-low emission zone (Ulez) in outer London has few rivals.

Sadly, it stands as a case study in political and administrative failure. It is also, equally balefully, another example of where what was once a powerful cross-party consensus on protecting the environment has melted away in the white heat of competitive electoral politics.

As with the latest relaxation of housing planning rules on water purity, and other symbolic downgrading of the green agenda by ministers, it does not bode well for the cleanliness of our home environment – or for the future of the planet.

Ominously, Labour’s Lisa Nandy seems to be acquiescing in this latest abandonment of environmental protection by Michael Gove and Rishi Sunak, a retreat in the face of the housebuilders’ bullying, and, at least in Mr Sunak’s case, quite a cheerful reverse.

He is in fact the least “green” premier in decades – even Margaret Thatcher made her famous green plea to the United Nations General Assembly. Backpedalling on his green new deal, Keir Starmer looks scarcely more committed.

It is indeed becoming painfully evident as to why there are no green causes in Mr Sunak’s famous five pledges; as his former climate change minister Zac Goldsmith pointed out in his resignation letter, Mr Sunak isn’t as interested in such matters as he should be.

The problem plainly crosses party lines. As the Uxbridge by-election demonstrated all too depressingly, little effort was made by the Labour mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, either to “sell” the policy effectively, or to consult properly worried residents subjected to scare stories about its impact – and, above all, the relatively high daily charge was to be implemented without sufficient motivations for the less well-off.

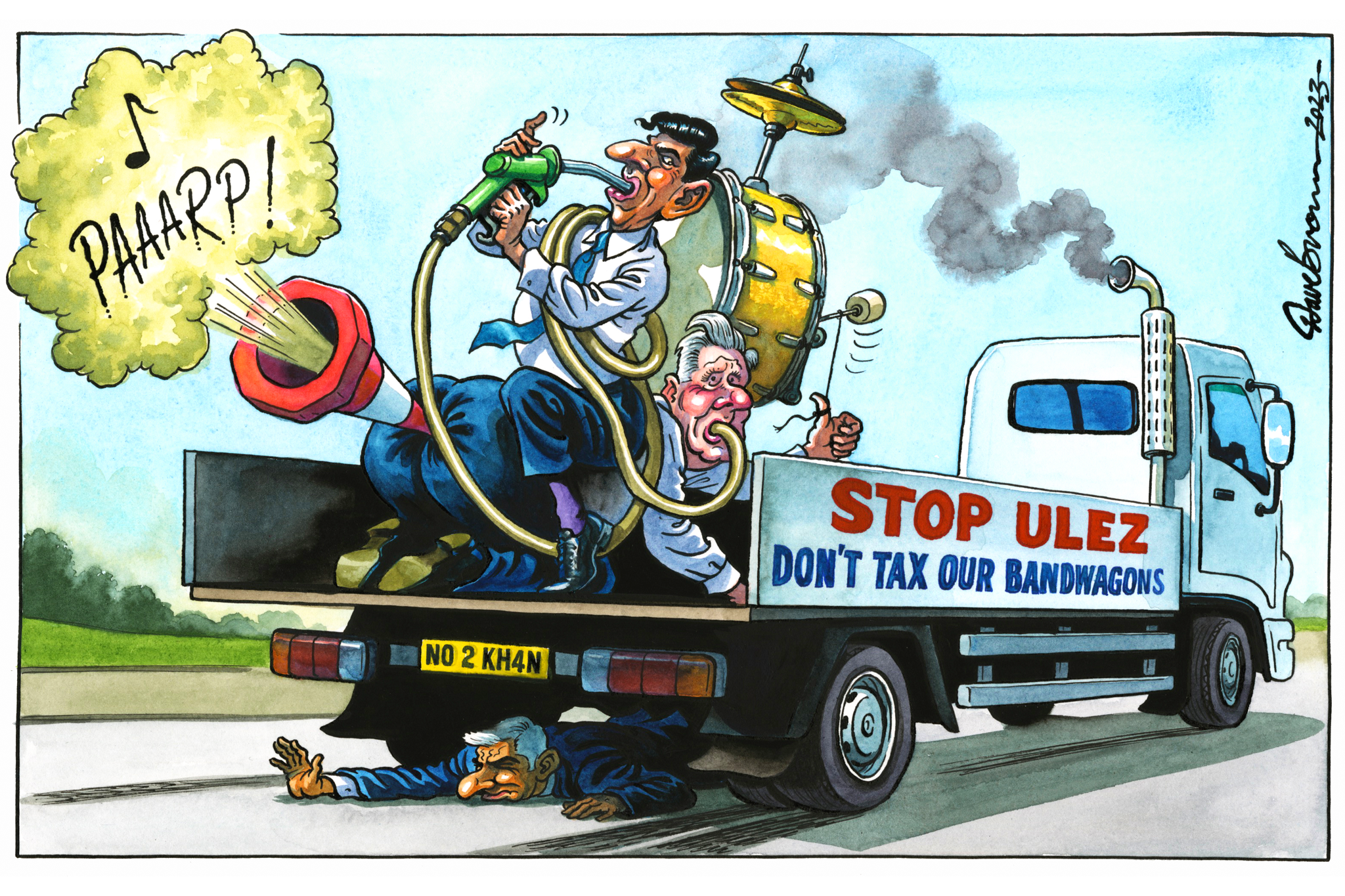

Mr Khan, seemingly lulled into complacency by flattering poll ratings and the lack of a dangerous mayoral Tory candidate, was asking for trouble once his political enemies got their hands on his well-meaning but poorly communicated initiative.

For reasons of pure short-term political advantage, the Conservatives were too easily able to portray the Ulez as a kind of poll tax on wheels, and they made the very best of the opportunity.

Tales from the by-election campaign included a couple with a Tesla zero emissions electric car on the drive complaining about having to shell out £12.50 every time its tyres touched the public highway.

Nationally and locally, Labour neglected to win the argument. They failed to produce sufficient evidence about the effects on lung health, especially among children; to point out that the government mandates clean air targets; that it was Boris Johnson, as mayor, who launched an inner London Ulez; and that implementing extension of the Ulez was a condition Grant Shapps laid down for a bailout of Transport for London.

Most of all, people in London and other large cities were left with the impression that most of them were about to be hammered by another tax on motoring – whereas the reality is that more than 80 per cent of drivers wouldn’t be troubled by the charge, and nice old classic cars more than 40 years old are also exempt: drive a Morris Minor and smile.

To many residents in Bromley, Hounslow, Barnet and elsewhere, it seemed illogical and offensive that new Range Rovers were and are exempt, but a 10-year-old Audi diesel isn’t. The arguments about nitrogen oxides and particulates – soot – were hardly aired.

Now that the charge is live, however, the policy ought to be able to speak for itself, as the great majority of drivers will soon realise they won’t be affected at all.

Many who are can access financial assistance, and it is not necessary to buy a £30,000 new electric car: many older petrol models will be compliant, as will newer diesels. Yet the fear that Labour mayoralties might make creeping changes in the Ulez rules as part of a stealthy but bogus “war on the motorist” remain.

The perfectly reasonable suggestion of road pricing based on emissions and actual road usage is also being traduced and weaponised by the newly anti-green right. Yet we have to reduce pollution, CO2 emissions, congestion and protect tax revenues as car usage shrinks and electric cars become mainstream.

On the road, as elsewhere, we cannot have our cake and eat it. The principle that “the polluter pays” is surely an eminently fair one. The wrangles and lies about urban ultra-low emissions zones represent a microcosm of what has gone wrong with environmental policy. It has happened quite suddenly.

In 2008, Gordon Brown’s government passed the Climate Change Act, the first of its kind in the world. It was enthusiastically supported by the Conservative opposition led by David Cameron, with only five rebel Tories voting against. Theresa May enshrined the target of net zero by 2050 in law. The Cop26 conference hosted by Boris Johnson in 2021 was a success.

The UK used to aspire to global leadership, and rightly. Now, shaken by soaring fuel bills and inflation, Britain is running away from environmental realities, science and its international obligations. We can surely do better than this.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks