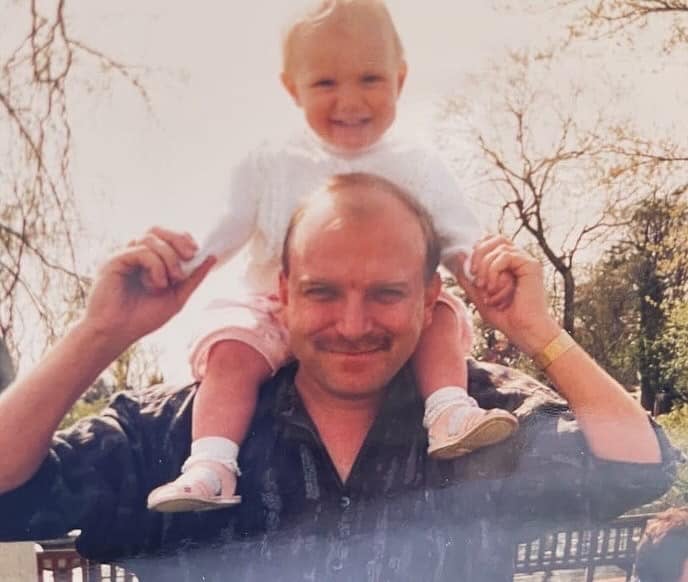

My dad had nine lives – so why was his death still such a shock?

Emma Marns’ father survived a lifetime of devastating tragedies, illnesses and surgeries. When his death eventually came, she found that years of fear and anticipatory grief had not prepared her for this loss

My dad very rarely, if ever, cried. But when he told me the story of how he collapsed in front of me when I was three, and all I did was calmly get him a pillow for his head and go and get my mum, his eyes would glisten slightly.

I didn’t remember this event, but I could well believe it, and when I think back now, three was probably about the age when I first understood that my dad was going to die.

By the time I was born, he’d already had a motorbike accident, a car accident, a career-ending football injury that led to his most severe illness – chronic osteomyelitis – and more than a dozen surgeries, including a tumour removal when my sister was six weeks old. He took dozens of tablets, was in and out of every hospital in the region, and struggled severely with his mental health.

When I was seven, Dad was paralysed after a surgery went awry. My mother worked, solo-parented and visited him on the other side of London to our Essex home. When she took us to see him, he sent us away after 10 minutes because he was so abundantly ill. He didn’t want to die in front of his children.

However, he didn’t die, and, in time, he regained use of the leg and came home. He even returned to work.

The next decade was hard. My dad’s illnesses were so severe, his hospital visits so unjustifiably frequent, that after a while, people at school stopped believing me. Surely, if he was that ill, he would die. I called home on lunch breaks sometimes just to check he was still there, or had got off to work OK. If my phone ever rang, I jumped out of my skin to answer it in a panic.

No one else I knew had an ill parent so perilously close to death. They either got ill and recovered or got ill and died. My dad didn’t seem to do either. I had no one to relate to, no one outside my family who could understand.

One day, on my way home from school, there was an ambulance outside our house.

My sister and I shut ourselves in the lounge, but it didn’t shield us from the sound of Dad screaming as the paramedics carried him down the stairs. They tracked an infection from his foot as it steadily gained pace towards his femoral artery.

It didn’t make it. But he did.

Dad underwent a surgery at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital – by the mid-2000s, it had become his home from home – in which the fluid surrounding his brain was accidentally drained. To say it gave him a headache would be a massive understatement. He was in critical condition, as critical as it gets.

While I was studying for my A-levels, Dad had a triple heart bypass that went badly. He was in so much pain that doctors told us he was at high risk for a stroke or a heart attack. The likelihood was he wouldn’t survive whichever he had. In the end, he had neither. He miraculously recovered and came home.

I duly went to university. Dad’s fragility plagued but also inspired me – I wrote top-mark exam essays on father-and-daughter relationships in Shakespeare and a short story about the Queen of Hearts becoming so on the day her father died. When I trained as a journalist, I had a particular interest in Paralympic sports and wrote about my experiences as a carer.

In 2011, a planned two-hour surgery turned into a seven-hour ordeal so traumatic that the surgeon took a sabbatical afterwards. The defibrillators came out, and Dad told me he remembered hearing the doctors arguing about whether using it was even worth it, as he was “already gone”. But he wasn’t. He recovered again.

By my twenties, I was a nervous wreck who needed at least five to seven business hours to recover from an unplanned phone call. The surgeries and hospital visits continued. I left work on occasion to sit with him at A&E. By my early thirties, other people started losing their hitherto very healthy parents. An old school friend lost his dad a mere six weeks after diagnosis. The feelings it stirred in me were complex – was I jealous? Not of their loss, but of the speed of which their ordeal took hold and completed? Yes, I suppose I was.

The fear and the anguish were exhausting. I had treatment for a fatigue that no doctor found the root cause for. In 2022, when my daughter was three months old, Dad developed sepsis and spent nine weeks in the hospital, including a brief stint in an end-of-life ward. It weakened him severely, but he made it once again. I wondered if anything was ever going to kill him. We joked in the family that after decades of torment, he’d outlive every one of us.

After 20 years of my jumping for the phone, Mum didn’t call when the time came, but sent a text. “Dad isn’t going to make it. If you don’t want to come, I understand.”

I held his hand when he took his last breath. He was ready; I wasn’t. I was 33. “Mister Nine Lives,” I wrote on Facebook. “Foiled at last.”

What shocked me most about the reactions to Dad’s death was people’s surprise. Colin? No. It cannot be. In turn, I was surprised by their surprise, given that he was the sickest man any of us knew. I realised then how we’d all taken his repeated recoveries for granted. Despite the constant dread, it seemed none of us had believed he really would ever die, and we didn’t know until it happened.

Exactly six months to the day of Dad’s death, my mother’s dear friend lost her husband to a heart attack in the middle of the night. The shock all but killed her too, and their kids. His funeral was held in the same place as my dad’s, and when I saw them all at the wake, I realised to my shame that, of course, they were just like us. They looked as we had looked. They spoke as we had spoken.

Thirty years of preparation had made no difference at all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks