Stargazing in September: Secrets of the Milky Way

Within the Milky Way you’ll find scattered dark regions that puzzled eighteenth-century astronomer William Herschel, Nigel Henbest writes

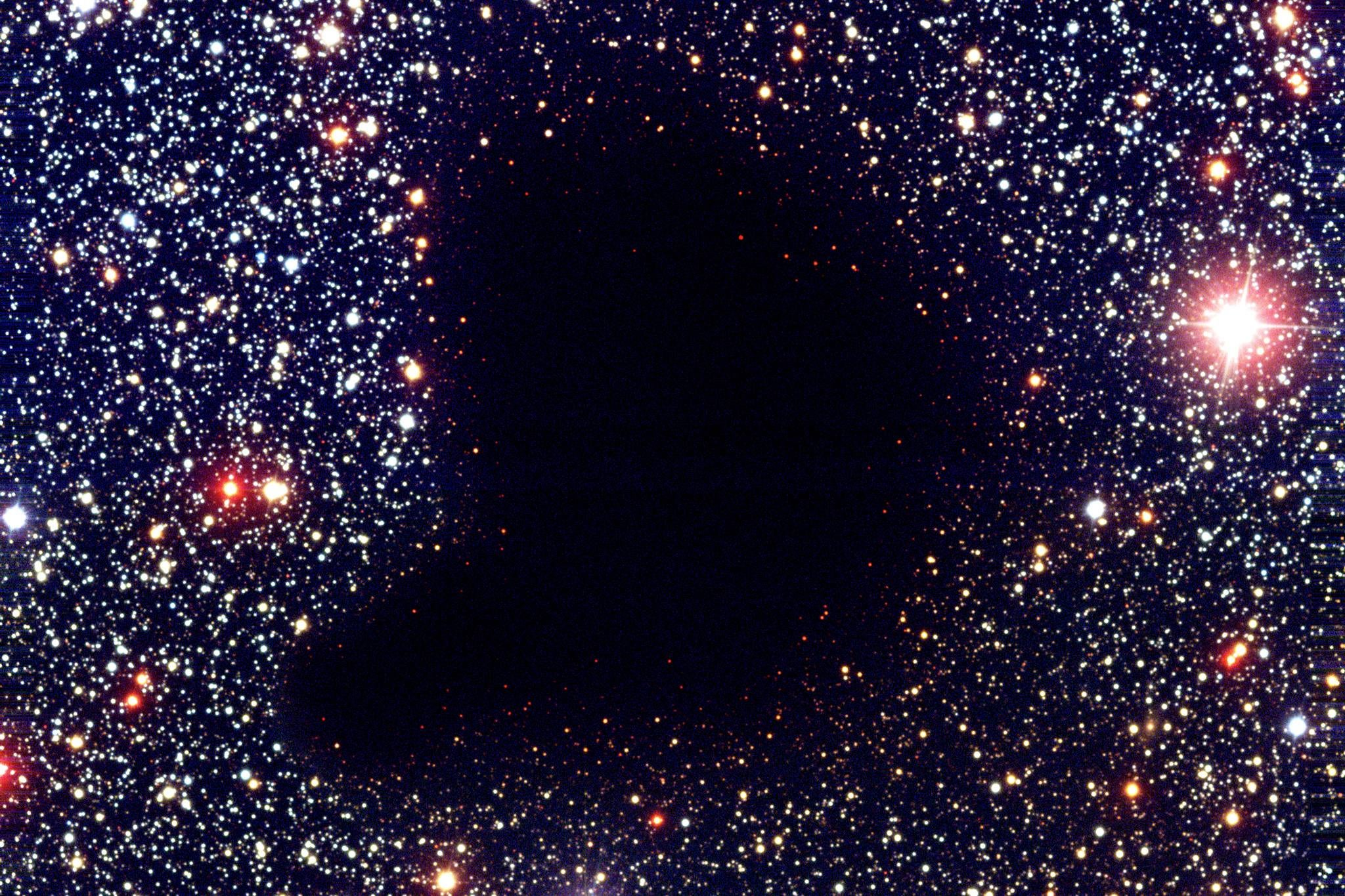

One of the glories of the night sky is on full display this month – but hidden from many of us by the curse of light pollution. On a moonless night, take yourself far away from streetlights and other artificial illumination; let your eyes grow accustomed to the dark; and look upwards. Arching through the heavens above us is a shimmering band of light: the Milky Way.

Named by the ancient Greeks and Romans – who believed it was milk spilt from the breast of the goddess Juno as she nursed the baby hero Hercules – the Milky Way in fact comprises the combined light of literally of billions of stars that make up the galaxy in which we live. In the seventeenth century, the great scientist Galileo resolved the glowing band into individual stars using his pioneering telescope. You can emulate his feat simply with the power of a pair of binoculars: sweep along the Milky Way, and you’ll see not just thousands of faint stars, but also the stunning jewel-boxes of star clusters and the shining gas clouds of bright nebulae.

But within the Milky Way you’ll also find scattered dark regions. These puzzled the eighteenth-century astronomer William Herschel – who’d just discovered the planet Uranus – as he was trying to map out the distribution of stars in the Milky Way. He called them “holes in the heavens”, and thought they were real gaps between the stars, where he could see out to space beyond.

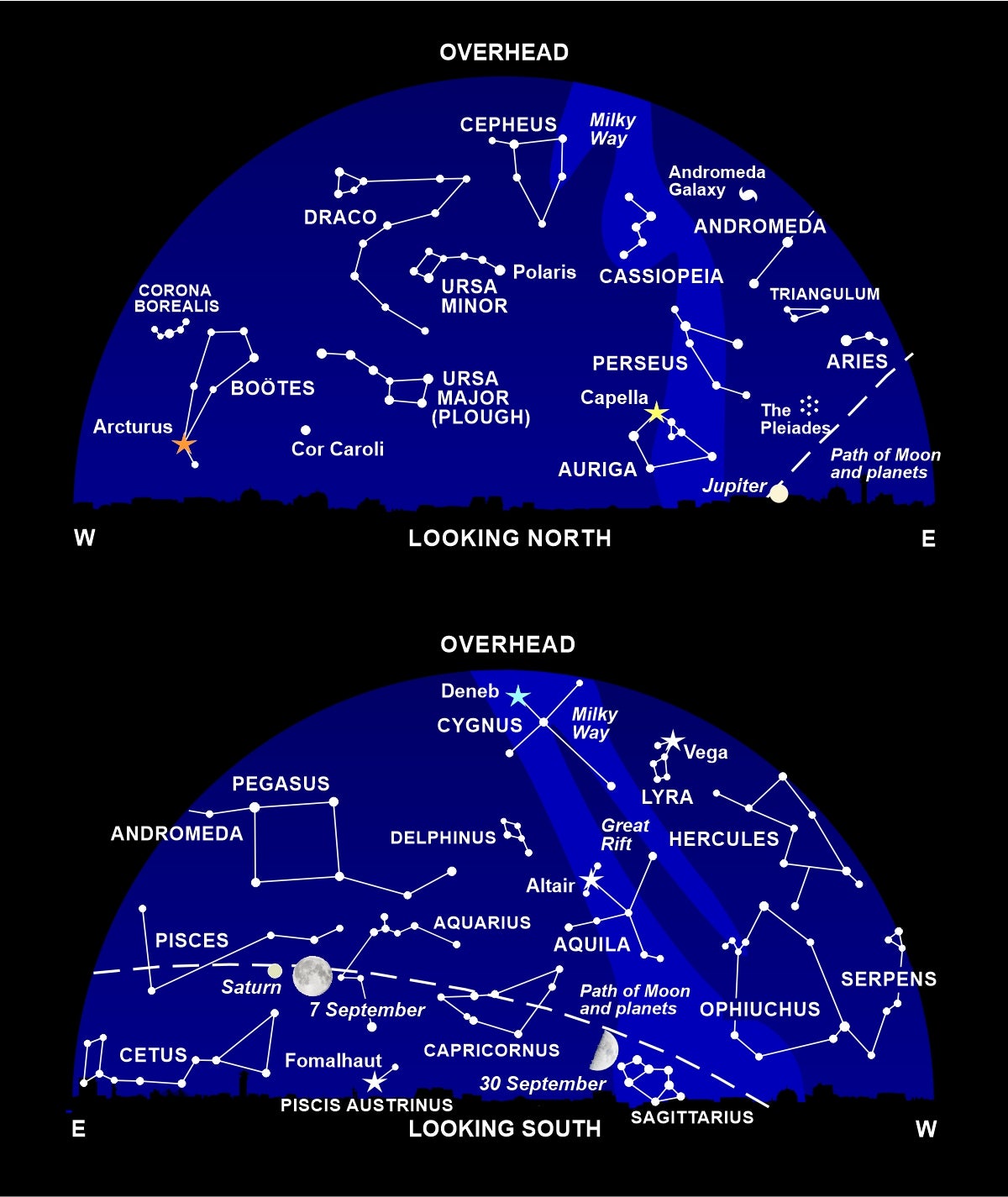

The greatest of these interstellar gaps dominates our view of the Milky Way as we look towards the south. As you can see in the accompanying star-chart, the Milky Way seems to split in two in the constellation Cygnus, near the bright star Deneb, with two branches heading downwards. While the lefthand star-stream reaches the horizon in Sagittarius, the righthand branch ends in Ophiuchus. Between them lies the dark expanse of the Great Rift.

While these dark gaps look like empty regions of space to the human eye, even through a telescope, their true nature was revealed early in the twentieth century by the American researcher E. E. Barnard. A skilled photographer, he turned to astronomy and had access to some of the largest telescopes of the time. Barnard systematically photographed and catalogued the dark patches in the Milky Way. His images showed clearly that they looked less like holes in the star distribution, and more like the silhouettes of dark clouds.

At that time, astronomer believed that space between the stars was a pure vacuum; so what were these obscuring objects? Barnard suggested that they were “dead nebulae.” Astronomers were well aware of glowing gas clouds like the Orion Nebula, and it was natural to think that one day their illumination would fizzle out. Barnard pondered “what would be the condition of a nebula that no longer emitted light… it is likely that we should simply have a dark nebula which would not be visible in the blackness of space unless its presence were made known by its absorption of the light of the stars beyond it.”

Barnard was certainly right in suggesting the gaps in the Milky Way are dark clouds, seen in silhouette. They are composed of microscopic grains of interstellar dust, which have been ejected by dying stars and now pollute space. The Great Rift in Cygnus is a dense band of interstellar soot that stretches for thousands of light years along a spiral arm of the Milky Way galaxy. Through perspective, it appears thinnest in its farther regions around Deneb; then broadens out as it runs closest to the Sun in Ophiuchus, where it obscures much of the Milky Way from our sight.

But Barnard’s insight failed when it came to the life story of a dark cloud. Instead of being wraiths of once-shining nebulae, these clumps of interstellar matter are their precursors. Astronomers now know that gravity will make the dust and gas in the centre of a dark cloud collapse into new stars; as they begin to shine the radiation from these fledgling stars will heat up their surroundings, and the once-dark cloud will shine as a glorious bright nebula.

What’s Up

The Moon is stealing the celestial show this month. On 7 September, our silvery companion slips into the Earth’s shadow, and is dimmed almost to the point of extinction in a total lunar eclipse.

Unlike solar eclipses, which are visible only from a narrow band on Earth, an eclipse of the Moon can be seen from an entire hemisphere of our planet. This month’s event graces the skies of all the major landmasses of the Earth, with the exception of the Americas. According to some estimates, the coppery coloured total eclipse will be seen – clouds willing! – by 85 per cent of the world’s population.

So much for the good news; but it’s not all jubilation for people living in the British Isles. For people in England, the Moon is totally eclipsed as it rises (around 7.30 pm), but you’ll find it difficult to spot the obfuscated Moon against the bright twilight sky. And by 7.53 pm the Moon has started to move out of the Earth’s shadow, with a thin sliver of its lower illuminated by sunlight. If you’re in Scotland or Ireland, you’ll miss the totality entirely: the Moon will rise already in its partial phase. In any case, we’ll be treated to the unusual sight of a crescent Moon not in the west where the Sun has set, but diametrically across the sky to the east.

The next night, 8 September, the Moon passes near Saturn. Distant Neptune lies between the two, but it will be hard to find – even with a telescope – so close to the Moon’s glare.

On the evening of 12 September, the Moon passes right in front of the Pleiades – the Seven Sisters star cluster – and hides several of its brighter members. Use binoculars or a small telescope to watch the stars blink out of sight behind the Moon’s airless globe, and reappear just as suddenly from its dark edge.

The Moon’s finale this month is a narrow crescent before dawn on 19 September, hanging just above brilliant Venus, with Leo’s leading light Regulus in close attendance on the Morning Star.

On the planetary front, Saturn is nearest to the Earth and at its brightest this year on 21 September. Jupiter is rising in the north-east soon after midnight; while in the dawn sky you’ll find brilliant Venus clearing the horizon around 4am.

Finally, there’s an eclipse of the Sun on 21 September, but it’s not total as seen from anywhere on Earth. The south Pacific and Antarctica are treated to a partial eclipse, but nothing is visible from the UK.

Diary

7 September, 7.09pm: Full Moon; total lunar eclipse

8 September: Moon near Saturn

12 September: Moon occults the Pleiades

14 September, 11.33am: Last Quarter Moon

16 September, before dawn: Moon near Jupiter

17 September, before dawn: Moon near Jupiter

19 September, before dawn: Moon near Venus and Regulus

21 September, 8.54pm: New Moon; partial solar eclipse; Saturn at opposition

22 September, 7.19pm: Autumn equinox

30 September, 12.54am: First Quarter Moon

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks