Stargazing in February: Mercury – a planet of extremes

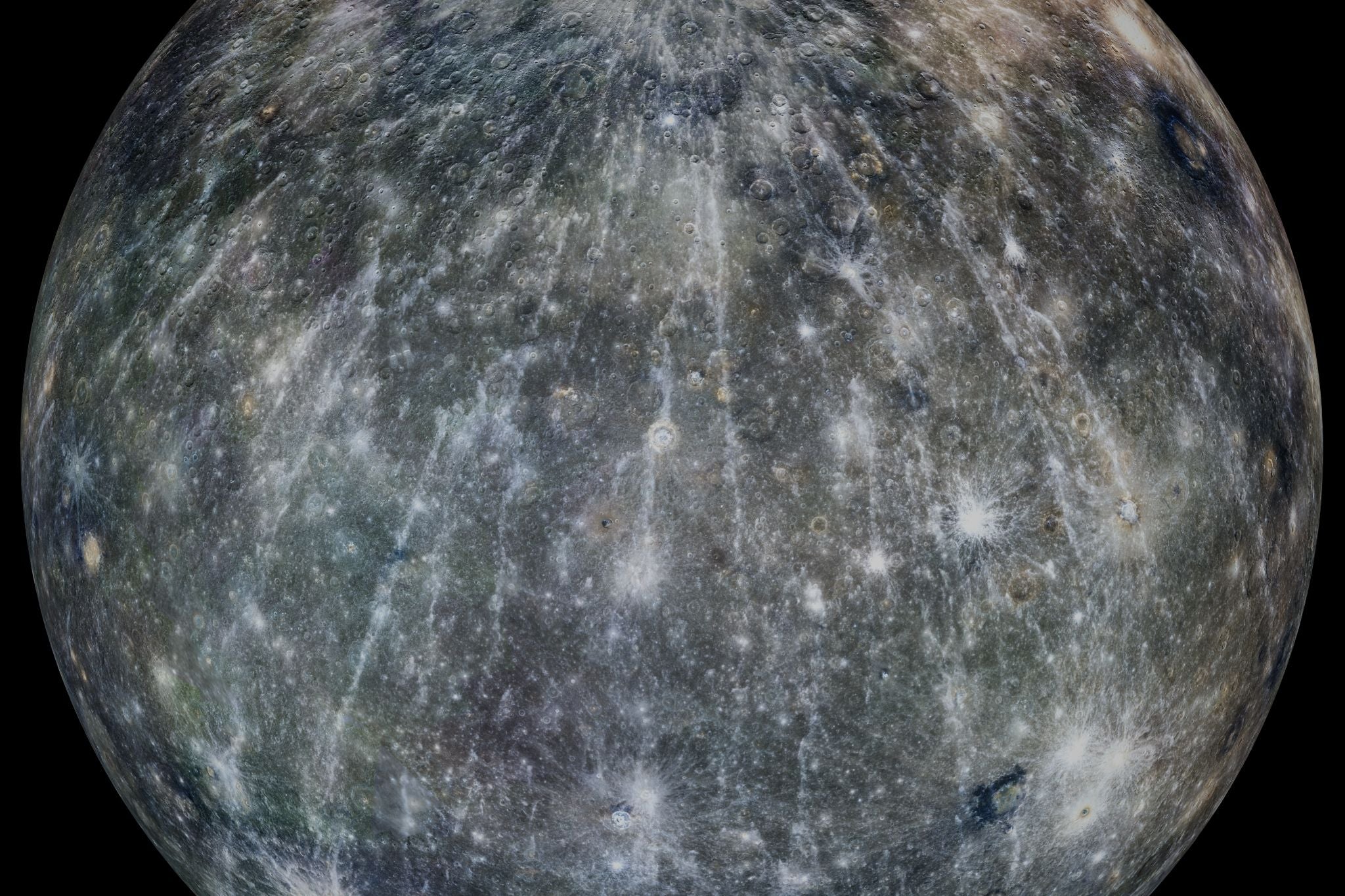

It may look like the Moon, but Mercury has many more secrets, Nigel Henbest writes

It’s a world where the Sun stops in the sky at noon and spins a small circle. Where you’d celebrate your annual birthday twice every day. In places, it’s as cold as the temperature of liquid air; while other locales are so hot that paper would spontaneously ignite – if this world had oxygen.

This is not a destination in Star Trek; nor is it one of the extreme planets that astronomers are now discovering that circle distant stars. It’s a world is right here in our Solar System; and this month you can see it for yourself, as Mercury puts on its best evening show of the year (see What’s Up).

As the innermost planet of the eight planets, Mercury never strays far from the Sun in our skies. Most of the time it’s lost in the daytime glare; and even at its greatest apparent distance from our local star, you’ll never see it against a fully dark sky. The great sixteenth century astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who put the Sun – rather than the Earth – at the centre of the planetary system, never observed Mercury himself; so give yourself extra plaudits for finding it this month!

Aptly named after the speedy messenger of the Roman pantheon, Mercury completes an orbit of the Sun in only 88 days, making its "year" less than three Earth-months. But it revolves at a much more leisurely rate around its axis, so that a "day" on Mercury – from sunrise to sunrise – is 176 Earth days, making a Mercurian day twice as long as its year. If you had your birthday one morning, the planet completes an orbit – bringing you to your next birthday – before the Sun has set the same day!

Mercury has the most elongated orbit of any of the Solar System’s planets: at its furthest point, the planet is 50 per cent more distant from the Sun than when it’s closest. As it travels round, Mercury’s orbital speed is constantly changing; but – on the other hand – its rotation around its axis is constant. Both affect the way the Sun seems to move across the sky. As we know on Earth, the planet’s rotation during the day makes the Sun appear to travel upwards from dawn to noon, and then descend and set. What we don’t see so easily is that the Sun seems to move gradually in the opposite direction as the Earth pursues its orbit.

For Mercury, with its extremely short year and excessively long days, the two effects are much more similar. When the planet is closest to the Sun, its orbital speed makes the Sun appear to move backwards more quickly than the planet’s rotation makes it travel forwards. As a result, there’s a period (just a few Earth-days long) when the Sun appears to stop and move backwards – performing a small loop – before resuming its daily motion.

Depending on where you are located, that loop might occur at any time of day: if you are in a region called the Caloris Basin, the Sun reaches this near-standstill at noon. At that time, Mercury is closest to the Sun, so this the hottest place on an already searing world, with temperatures reaching 420C. In contrast, there are craters near Mercury’s poles so deep that the Sun never shines inside: these regions freeze at the temperature of deep space, around -170C.

Going back to the nineteenth century, one of the greatest puzzles in astronomy was the rate at which the long axis of Mercury’s oval path swings around in space. Even allowing for the pull of all the known planets, it just didn’t fit with Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity. Astronomers posited a planet, named Vulcan, that orbited closer to the Sun and pulled Mercury out of position; but no such world was visible, even during total solar eclipses.

The answer came in 1915 from innovative mind of Albert Einstein. His new theory of gravity, General Relativity, accorded with Newton’s theory where gravity is weak. But Mercury is so deep in the Sun’s gravitational field that Newton’s theory failed. Einstein’s success in explaining Mercury’s motion established his theory of gravity – which has gone on to explain everything from black holes to the Big Bang.

Visiting spacecraft have shown that Mercury’s surface is pockmarked with craters, like our Moon. Recent impacts have thrown long rays of ejecta far across the planet. But deep inside, the planet holds another mystery: a huge iron core.

Astronomers have two theories to explain this oddity. Maybe searing heat from the early Sun – right on Mercury’s doorstep – boiled away most of the rocky material that should have condensed onto the forming planet’s iron core. Or perhaps Mercury was born with a core plus a thick rocky mantle, like Venus or the Earth, but a near collision with another world stripped away its surface layers.

We hope the answer will become clearer later this year, when the European-Japanese spacecraft BepiColombo slips into orbit around Mercury. Its sensitive instruments will measure the planet’s composition and details of its core, and finally reveal what tumultuous events shaped the most enigmatic of the Sun’s diverse family of worlds.

What’s Up

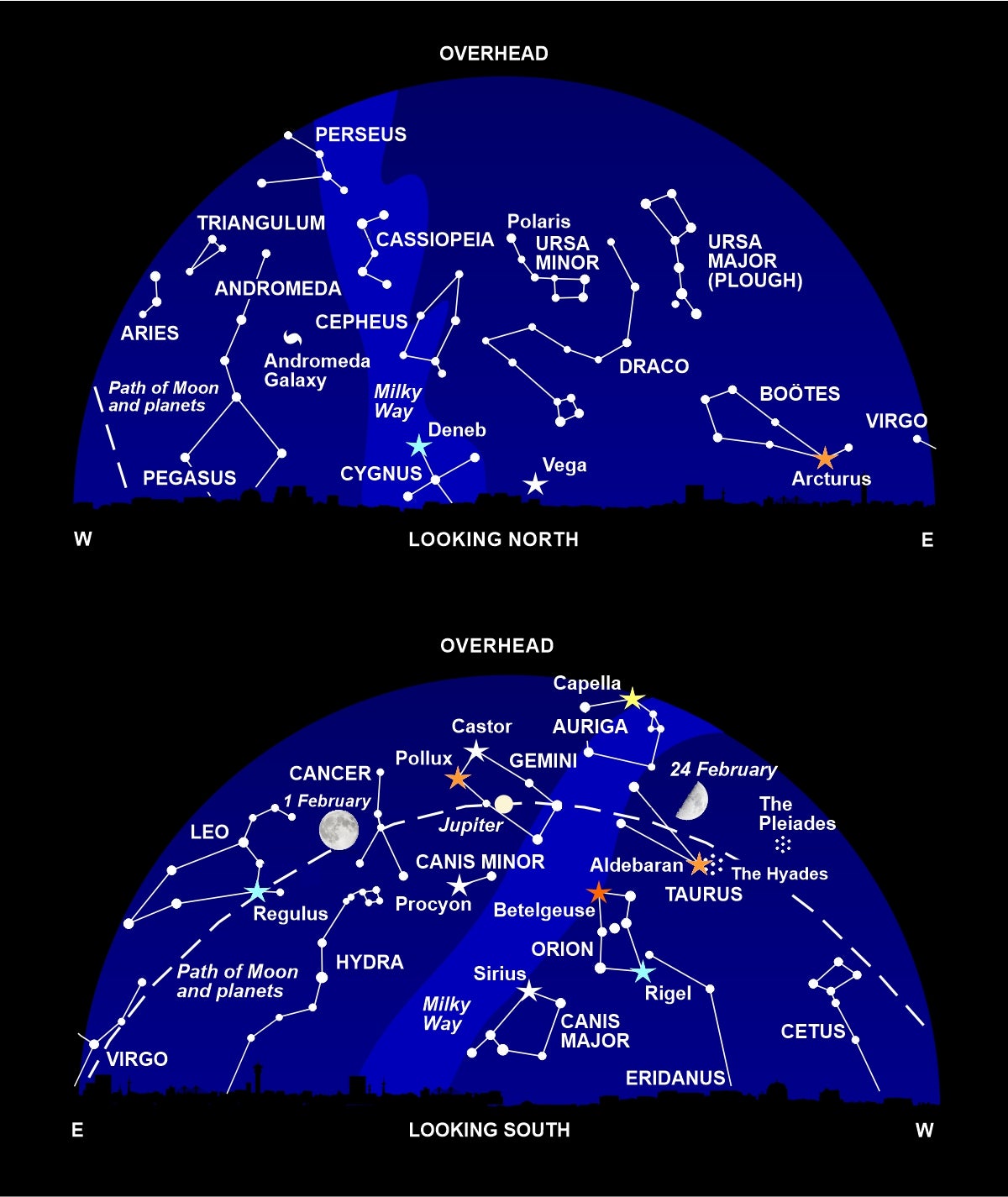

If you love planets, this is the month for you! At the start of February, Jupiter is the most brilliant planet on view, high in the south all night long near the twin stars Castor and Pollux. The Moon lies near the giant planet on 26 and 27 February. Below Jupiter you’ll find Orion (the hunter) with the brightest star, Sirus, to its lower left.

In the west, Jupiter’s more distant sibling, Saturn shines in a region devoid of prominent stars. From 8 February, you’ll find a brighter interloper to the lower right of Saturn, down in the twilight glow: this is Mercury, putting on its best evening appearance of the year.

Around the middle of the month, an even more stunning planet appears below Saturn and Mercury – the glorious Evening Star, Venus. Night after night, it rises higher and by the end of the February it’s dominating the dusk view.

The Moon joins in this planetary dance: on 18 February there’s a narrow crescent Moon between Venus (below) and Mercury (above); and on 19 February the crescent Moon lies above both Mercury and Venus, with Saturn to its left.

And here’s a challenge: if you have good binoculars or a small telescope, try to spot the most distant planet, Neptune. This remote world is too faint to see with your unaided eye, and even in a small telescope it looks so much like a star that it’s hard to find among the multitude of stars in the sky. But on 20 February, Saturn passes Neptune and you’ll have a great chance to spot the most distant planet as a faint blue-green ‘star’ about two Moon-widths to the right of Saturn.

There’s an eclipse of the Sun on 17 February, but you’ll have to be in Antarctica to see it!

Diary

6 February: Moon near Spica

9 February, 12.43pm: Last Quarter Moon

17 February, 12.01pm: New Moon; annular solar eclipse

18 February: Moon near Mercury and Venus

19 February: Mercury at greatest elongation east; Moon near Saturn

20 February: Saturn near Neptune

24 February, 12.27pm: First Quarter Moon

26 February: Moon near Jupiter

27 February: Moon near Jupiter

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks