Inside the vast underground bunkers ready to protect Helsinki from Putin

Carved into the bedrock deep below Helsinki is a series of underground bunkers where the entire city’s population can shelter in the event of an attack. Annabel Grossman explores this vast network and learns how Finns plan to protect their citizens in the face of a hostile neighbour to the east

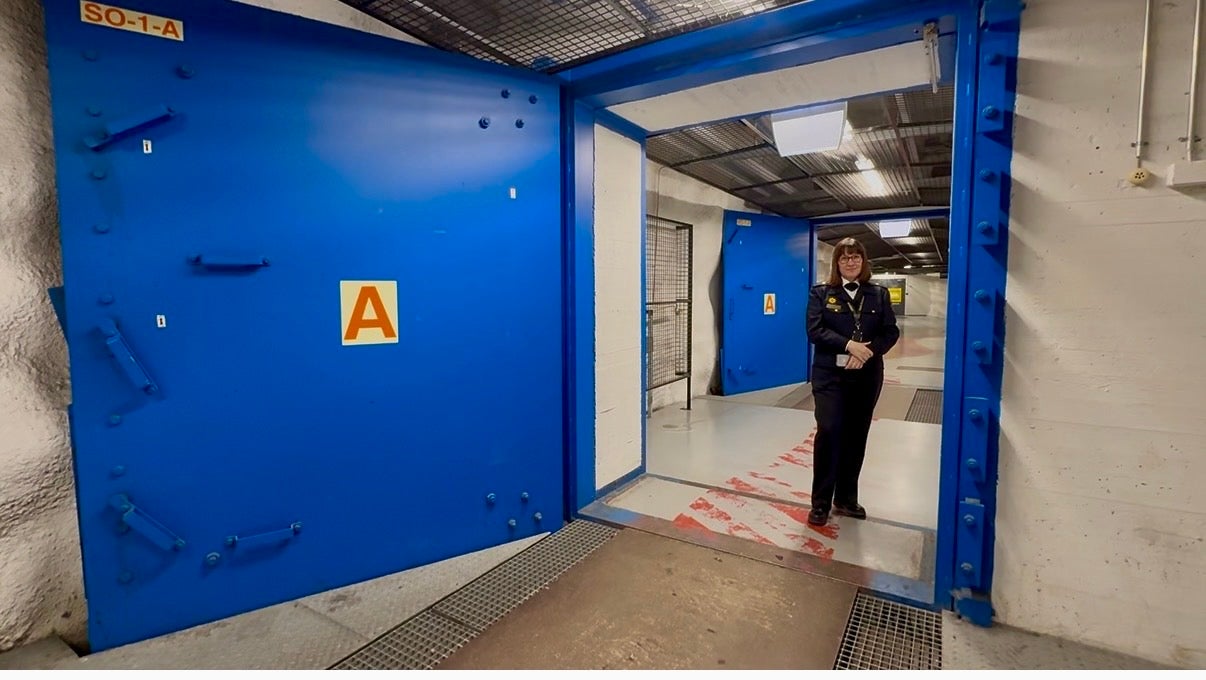

A thick granite wall designed to withstand multiple blasts separates the two heavy metal doors at the entrance to Merihaka shelter in central Helsinki.

In an emergency, after passing through this double entryway, local residents arrive in a sealed decontamination chamber where there are taps and showers to wash toxic materials from clothing, before passing through into the main bunker cut deep into the bedrock 25 metres below Finland’s capital.

Merihaka is just one of many in Helsinki’s vast network of underground shelters – with winding tunnels and expansive chambers – designed to withstand a nuclear attack, as well as heavy shelling, and capable of holding hundreds of thousands of people.

“We are prepared,” Nina Järvenkylä, from the Helsinki Rescue Department, tells The Independent as she gestures to the neatly stacked bunk beds and line of dry toilets. “If there’s a war, we know what to do.”

In the event of an attack, the bunker can hold up to 2,000 people – although at full capacity it would be cramped with bunks three beds high – and can be fully sealed thanks to its ventilation system.

The halls can be divided by curtains to create separate spaces for children, privacy for the elderly, or to administer first aid.

Given the proximity to Russia (the countries share a 1,343km-long border from Lapland in the north to Karelia in the south) and a turbulent history, Finland’s preparedness for conflict is perhaps unsurprising.

“We have had 80 years to prepare,” adds Järvenkylä. A shelter system has been in place in Helsinki since the Second World War, during which time Finland lost the eastern province of Karelia to Russia, and the city has been continually strengthening the system since.

The occupation of Crimea in 2014 and Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 highlighted the possibility of traditional warfare, shaping the Finnish government’s shift to a strategy of comprehensive security, with a capacity to protect all members of the population in the event of military threat.

In common with a number of shelters across Helsinki, the Merihaka bunker has a double use, with a number of the halls fitted with sports facilities, a cafe and a children’s play area.

The space is rented out by the city on the agreement that it can be cleared within 72 hours in the event of an emergency.

The process is clear: a city-wide siren will sound (this is tested on the first Monday of every month) and an app alert will be sent out to mobile phones – at which point all Helsinki residents are advised to gather a backpack of food, medicine, toys for children, and any personal belongings, and head to their nearest shelter.

There is a designated shelter space for every person in Helsinki – with a population of around 700,000, the city has shelter space for close to 950,000 – that should be able to be reached in one to 10 minutes.

There are around 5,500 civil defence shelters in the city and some 50,500 across Finland accommodating a total of 4.8 million people, which equates to about 85 per cent of the population.

Early evening on a Thursday, Rebecca Harkonen, 27, is playing with her two young sons in the children’s area, bouncing on trampolines and clambering on a soft climbing frame.

The thwack of plastic balls against sticks as a children’s hockey game takes place in one hall and the laughter of toddlers stands in stark contrast to the underground caverns’ primary purpose as shelter from attack.

As her giggling four-year-old dives headfirst into the ball pit, Harkonen says: “We all know where our closest shelter is. That’s normal for us.”

Harkonen refers to the 72-hour concept that is well-known across Finland and details the level of home preparedness expected.

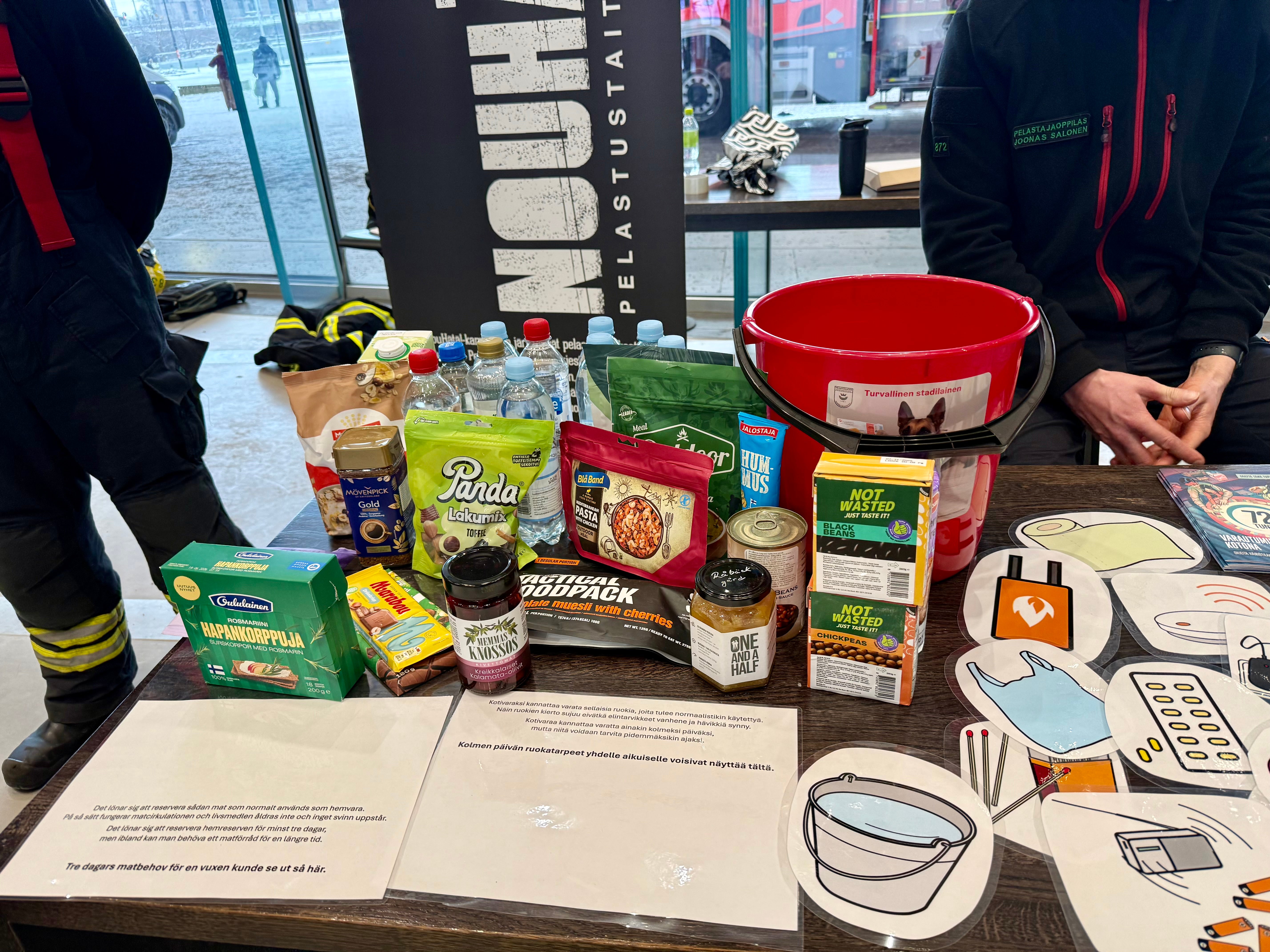

It is recommended that at all times, residents have three days’ worth of food, water and medicines, as well as essentials such as a battery-powered torch, iodine pills, a portable stove and matches, and a portable extinguisher.

She says she currently has 72 hours’ worth of most supplies, including canned food, as well as items in plastic bags like beans, lentils and oatmeal, and rye bread in the fridge because it stays fresh for three days.

The previous day, emergency services at the city’s large public library were handing out leaflets on the 72-hours concept and educating residents about what this volume of food should look like.

One fireman points to a selection of bottled water, freeze-dried packets, jars of coffee and canned food that roughly constitute three days’ worth of food supplies.

The leaflet adds: “It would also be important to know the basics of preparedness, such as where to get reliable information during a disruption and how to cope in a residence that is getting colder and colder.”

Lt Col Annukka Ylivaara, assistant secretary general of the government’s security committee, points out that the Finnish people are not panicking and they are not hysterical, but they are aware that there is a threat across the border and they have always taken that seriously.

She tells The Independent: “In a conflict situation, Finland would be ready. We have kept our conscription system and our reservist army. So it’s something that we are prepared for if it is needed.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks