How Donald Trump’s budget cuts could devastate rural communities in Kentucky

The state voted heavily for the new President. But with vital funding under threat, doubts are starting creep in over whether the former property tycoon can deliver the better deal he promised

Chad Trador was, like many people here, a onetime coal miner struggling to find work. He, his three children and his wife stayed afloat in a tough economy for years, but after he was laid off from his job managing a convenience store, the unemployment epidemic in this region appeared to have finally reached him, too.

“The best opportunities I had were another convenience store, maybe as a clerk, making minimum wage,” says Trador, 43, reflecting on last year. “And then I heard that radio ad.”

The intensive 33-week job training programme being advertised – TechHire Eastern Kentucky – promised to teach him computer coding from scratch. It would even pay him decent money while he learned. Trador signed up, and he is on track to complete the training in April, when he will emerge with a job as an Apple iOS developer.

Like many such programmes and infrastructure projects here in eastern Kentucky and across Appalachia, the job-training course has the US federal government’s fingerprints all over it. The Appalachian Regional Commission, an independent federal agency, helped jump-start it last year with a multiagency $2.75m (£2.2m) grant to a state organisation that developed it.

But after decades of work, the commission’s future is in doubt, with the Trump administration’s 2018 budget proposal threatening to eliminate funding for the commissions and other rural development endeavours. Voters in this part of the country, which overwhelmingly supports President Donald Trump, could be disproportionately affected if that happens.

Trador, who voted for Trump, says the cuts are a bad idea. The job training programme’s funding is secure for several more years, but the absence of further investment, he says, would exacerbate the region’s deep poverty.

“I think it’s horrible. I think that maybe there are some things that don’t need to be funded, but don’t cut things that are working like the Appalachian Regional Commission and the work that they’ve done,” Trador says.

As a political statement, Trump’s budget proposal delighted many small-government conservatives, whose long-held wish for a more focused, less-wasteful government appeared ready to be fulfilled. As a practical political matter, though, the proposed budget’s cuts to pocketbook programmes such as this one have few friends in Congress, where members’ political stock often rises and falls based on what they can do for constituents. The result will likely be a final federal budget that bears little resemblance to the one Trump proposed.

In a statement last week, Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, from Kentucky, said he would not allow any cuts to the Appalachian Regional Commission, pitting the powerful Republican against a Trump budget priority and opening the door for fellow GOP lawmakers to do the same. Harold Rogers, the US House Appropriations Committee chairman, said he understands that Congress and the White House “have a responsibility” to reduce the deficit. But he worries that cuts to such programmes could hurt his Eastern Kentucky district.

“I am disappointed that many of the reductions and eliminations proposed in the President’s skinny budget are draconian, careless and counterproductive,” said Rogers, who was first elected in 1981 and is Kentucky’s longest-serving member of Congress.

Because so much of the Appalachian commission’s budget – $146m in 2016 – goes toward infrastructure projects, many of the people living in communities that have benefited from the funding are unaware of its impact. The federal funding often goes toward repairing essential services rural towns cannot afford on their own, such as fixing broken sewer systems and revitalising community centres.

Wendy Collins, smoking a cigarette outside a dollar store in rural Frenchburg, Kentucky, grew frustrated when she heard about the recommended cuts to Appalachian development. In recent years, using a community development block grant from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and a commission grant, Frenchburg has received a combined $1m to develop a senior citizens centre and a regional meal-assistance kitchen.

HUD’s community development grants also would disappear with Trump’s proposed budget.

“Really? Wow. So now what?” Collins says. “The government shouldn’t take it away. This place is below the poverty level. There is nothing here, and people need something to stay out of drugs.”

Collins, 45, who draws disability benefits, becomes emotional as she speaks about her own involvement with drugs; she estimates she has known about 30 people who have died from opioid abuse. A Trump supporter, Collins says she could not vote for him because she has a felony drug conviction. She thinks Trump should visit the area to see the impact of his budget for himself.

“This community has nothing,” she says. “It needs help.”

But some of Trump’s supporters in the region appear willing to accept development funding cuts because they believe Trump’s broader agenda will help revitalise the region. The President has promised he will bring the coal economy back to life by cutting industry regulations, though experts have largely dismissed the effect such actions would have on jobs.

“As we speak, we are preparing new executive actions to save our coal industry and to save our wonderful coal miners from continuing to be put out of work,” Trump told a crowd in Louisville on Monday. “The miners are coming back.”

David Conn, 49, of West Liberty, Kentucky, says he is hopeful Trump can deliver. Conn, a coal miner, says that the region’s problems hinge on the loss of coal jobs. He doesn’t think that will be fixed with federal funding.

“It’s not Trump’s fault if the money’s not there. Somebody’s got to say enough is enough,” Conn says. “People on low income that may be abusing medication ... sometimes a line’s got to be drawn. I still stand behind him with that.”

West Liberty last year benefited from more than $250,000 in Appalachian Regional Commission funding, which went into improvements to the area’s water infrastructure.

Johnny Kouns, of rural Inez, Kentucky, voted for Trump and remains confident that the President can help redevelop the Appalachian economy. Kouns, 59, worked in coal fields until 2010. When the industry began to contract, he had to take early retirement.

“I think he’s doing pretty well considering what he had to take on,” he says. “But it’s not all going to bloom overnight. There’s a lot of work to be done, and there’s a lot of things coming at him.”

The federal government, through the Appalachian commission, provided funding for the Roy F Collier Community Centre in town to expand its programing with the Dream Discovery Centre. The centre will promote science and technology education.

Many in the region share the view that coal can be revitalised, and while Trador agrees that perhaps some coal jobs could be brought back, he says the region needs to diversify its economy. He says programmes such as his job training – which served an initial class of 50, of which about 35 continued on after the “boot camp” phase – can be scaled outward over time.

“I think coal can be part of this, but I don’t think coal is the end solution,” he says. “That’s a finite thing. As long as we have the internet, we can work anywhere.”

Some voters here conflate federal funding of assistance programmes – such as food stamps – with those that fund infrastructure and community development. Shane Estes, 43, of Elliott County, grows cynical when asked about the cuts. He says the money would not make a difference in the area anyway because the culture has been too polluted with drugs. Estes, who voted for Trump, says that some employers in the area have stopped drug testing workers because that would mean they could not hire anyone. And he takes issue with people using food assistance dollars on junk food.

But what about spending on infrastructure?

“Not here,” he says. “It’s going to get worse around here. It’s not going to get no better. I don’t think Trump can change this; I don’t think anything can.”

Many community leaders who have worked with the grants fear that cuts to federal funding could stymie revitalisation.

Danielle King purchased an abandoned building – empty since 1997 – in downtown Mount Sterling seven years ago. She restored it and turned it into a once-a-week bakery. She’s an internal medicine doctor by trade and has since hired employees to keep the bakery open most of the week. “We’ve created jobs!” she says. King has become an advocate for revitalising the entire downtown as a member of the town council, to significant effect. Walking through Mount Sterling, King spoke excitedly as she pointed to several new shops that have joined hers on the street.

“The only thing that was downtown was banks and lawyers,” she says, pointing around. “And this used to be all liquor and bars.”

Mount Sterling has been successful in cleaning up its main street. And it has benefited greatly from federal dollars: there are apartments for the elderly and disabled funded with HUD housing grants, and a $1m grant in 2010 helped clean up a blighted neighbourhood to the north, which had become a centre for crime and drug activity.

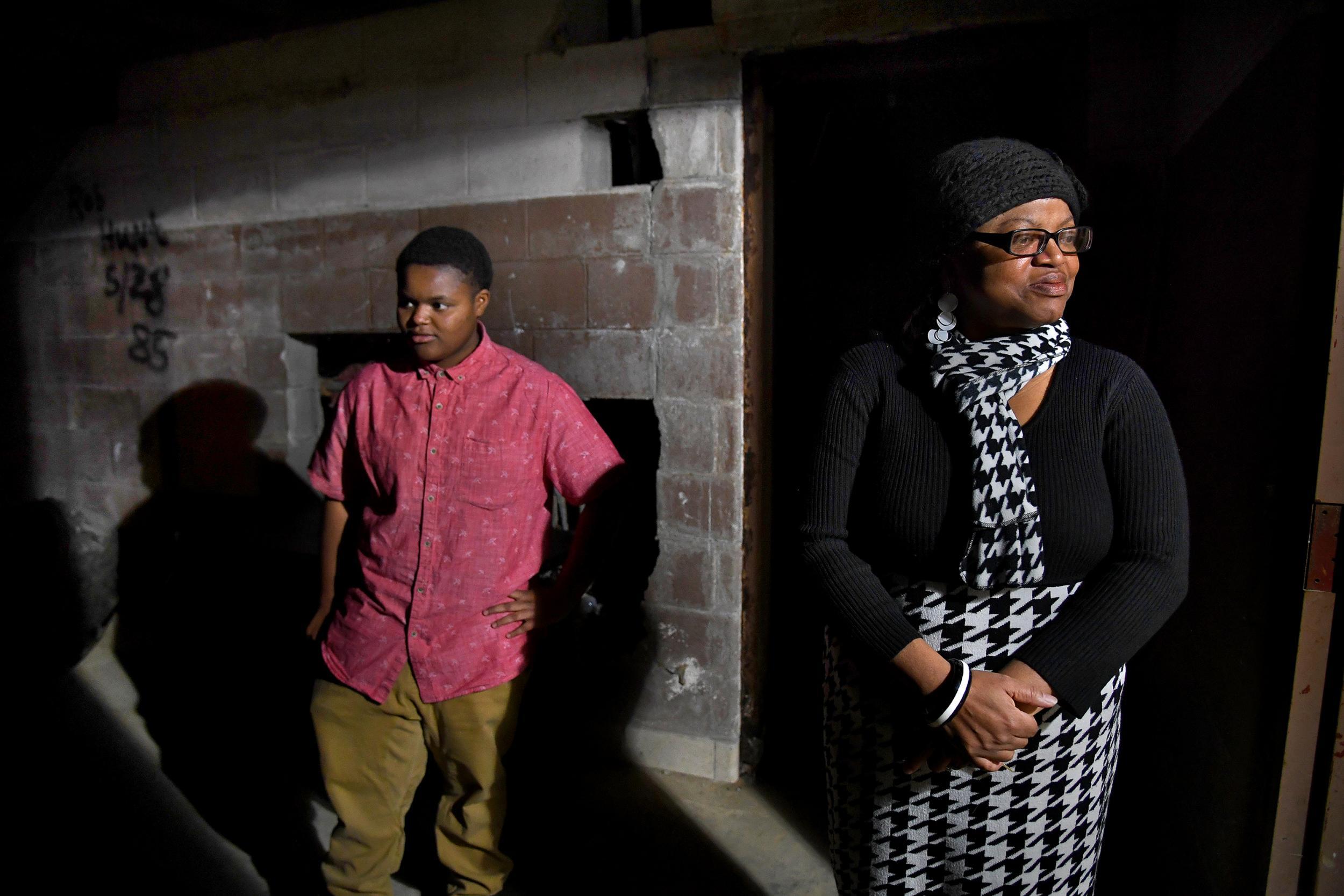

About a mile away, Valerie Scott checks on the newly installed gym floor at the Dubois Community Centre, which she and a community board have helped revitalise through commission and community development grant money to serve a largely African American community in the surrounding neighbourhood. She says Dubois closed several years ago because of structural problems that rendered it unsafe, leaving the neighbourhood without a place to gather.

“That was pretty hard for our community because it was utilised a whole lot. We’re a black community, very small but very strong in this area,” Scott says. “This is a very historical area. We wanted to revitalise it and get it back open.”

Below the main floor, another level remains stripped and dilapidated. Scott hopes another grant might allow the downstairs to become an educational space.

King is eager to accelerate the success Mount Sterling has seen. She is reluctant to comment on Trump or the budget cuts, but she says that rather than eliminating grants, the government should be more active when communities have a plan to move forward.

“When you’re in a big city, it’s like the money just rolls in. Everybody gets a piece of the pie. But when you’re a smaller place, they don’t look at you as viable so they don’t want to waste money on you,” she says. “They don’t see our needs; they don’t live here.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks