The great cellphone purge in schools — something both sides of the aisle can agree on

Educators and state legislators across the nation are pushing to banish smartphones from the classroom as evidence mounts that compulsive tech use is harming young people, reports Io Dodds

Cigarettes, backpacks, short skirts, firearms and books. Now, you can add a new item to the banned-in-school list - the smartphone.

From California to Texas to Maine, both state legislatures and individual school districts are cracking down on screen time in the classroom, often implementing total "bell to bell" bans on personal devices. The goal of the bans is to reduce distractions in the classroom and improve kids’ learning outcomes, while also reducing their overall screen time and thus their exposure to digital dangers.

What's more, the push is bipartisan — which is almost stunning in the second Trump era. Throughout 2025, red and blue state governors joined the crusade with equal ardor, while on Capitol Hill, Virginia Democrat Tim Kaine and Arkansas Republican Tom Cotton moved to grant extra funding to schools piloting such bans.

"Phone bans in schools are wildly popular with parents and with educators," Vaishnavi J, a veteran online child safety consultant who was once head of youth policy at Instagram's parent company Meta, tells The Independent.

"They're initially met with resistance by the students themselves, but shortly after the restrictions come into effect, a lot of children and teens report feeling higher levels of attentiveness, [being] more in the moment."

It is, Vaishnavi J says, akin to the mass bipartisan support for new laws against texting while driving, as well as the massive push to get computers into schools during the 1990s and 2000s.

Most of all, Vaishnavi J argues, these bans don't require complicated technological solutions to enforce: schools already know how to confiscate and regulate physical items. That makes them "a very attractive proposition" for any politician wanting to "show that they're making some progress around child safety."

Indeed, 69 percent of Americans now support banning cell phones from K-12 classrooms, according to a Fox News poll in December, with both Republicans and Democrats being mostly in favor (though with quite different margins).

"I think these bans are just a great start. We should largely strive to make schools completely screen free," said conservative commentator Karol Markowicz in an interview with Lara Trump on her Fox & Friends spot last week. "Kids don't have attention spans anymore."

A growing body of alarming evidence

Much of the credit for this tidal wave can go to the psychologist and prolific centrist pundit Jonathan Haidt, who led the charge with his best-selling 2024 book The Anxious Generation. His work has been trumpeted by both Arkansas governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders and New Jersey's Phil Murphy, both of whom have several children.

"Everyone is a parent, everyone has kids... everyone sees this," Haidt told Politico in September.

Haidt's book drew together numerous studies to argue that smartphones and social media were behind a widespread rise in mental health diagnoses, self-harm and suicides among people under 18 years old since 2010.

Some scholars and researchers have pushed back on those claims, arguing that Haidt's evidence isn't enough to blame technology alone and accusing him of peddling simple answers to a complex set of problems.

According to Stanford professor Thomas Robinson, who has been studying the impact of screen time on children since the early 1990s, it's true that the academic evidence is lacking. "A preponderance of null and weak results make it difficult to conclude effects one way or another," he tells The Independent.

Yet much of that, he argues, is due to limitations in research methods — not least the difficulty of measuring kids' actual activity on smartphones rather than just what they tell researchers.

In a recent study designed to fix those issues, but which has not yet been peer reviewed, Robinson and other researchers measured 163 teenage users' actual activity via a background monitoring app. While the specifics varied between individuals, there was intensive use during school hours, very little of which was actually related to their schoolwork.

"In younger children, on the whole, many types of evidence lean toward harms. In teens, the evidence of harms also outweigh the evidence for benefits," Robinson says.

Robinson's findings mirror another recent study led by Dr. Jason Nagata, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, which found that teens spent more than an hour on their phones during the school day — mostly on social media, videos or gaming apps.

Nagata's research has also found that social media use before age 13 is associated with poorer performance on reading, memory and vocabulary tests two years later. "[These] findings align with recent school phone bans and efforts to promote age-appropriate screen habits," he told The Independent.

In any case, Robinson says, what's really driving these bans is that parents and teachers feel they are seeing blatant problems unfold right before their eyes, with anxious and distracted teens constantly glued to their portable magic mirrors.

"I’m living this real time, right now," Sarah Huckabee Sanders told Politico.

How do the bans work?

The exact approach differs widely between schools. Plenty already had rules against students having their phones out during class, and some have tried to divide up the premises into smartphone 'green zones' and 'red zones'.

But such policies are difficult to enforce, and easily defied — as anyone who's ever made trouble behind a teacher's back can attest.

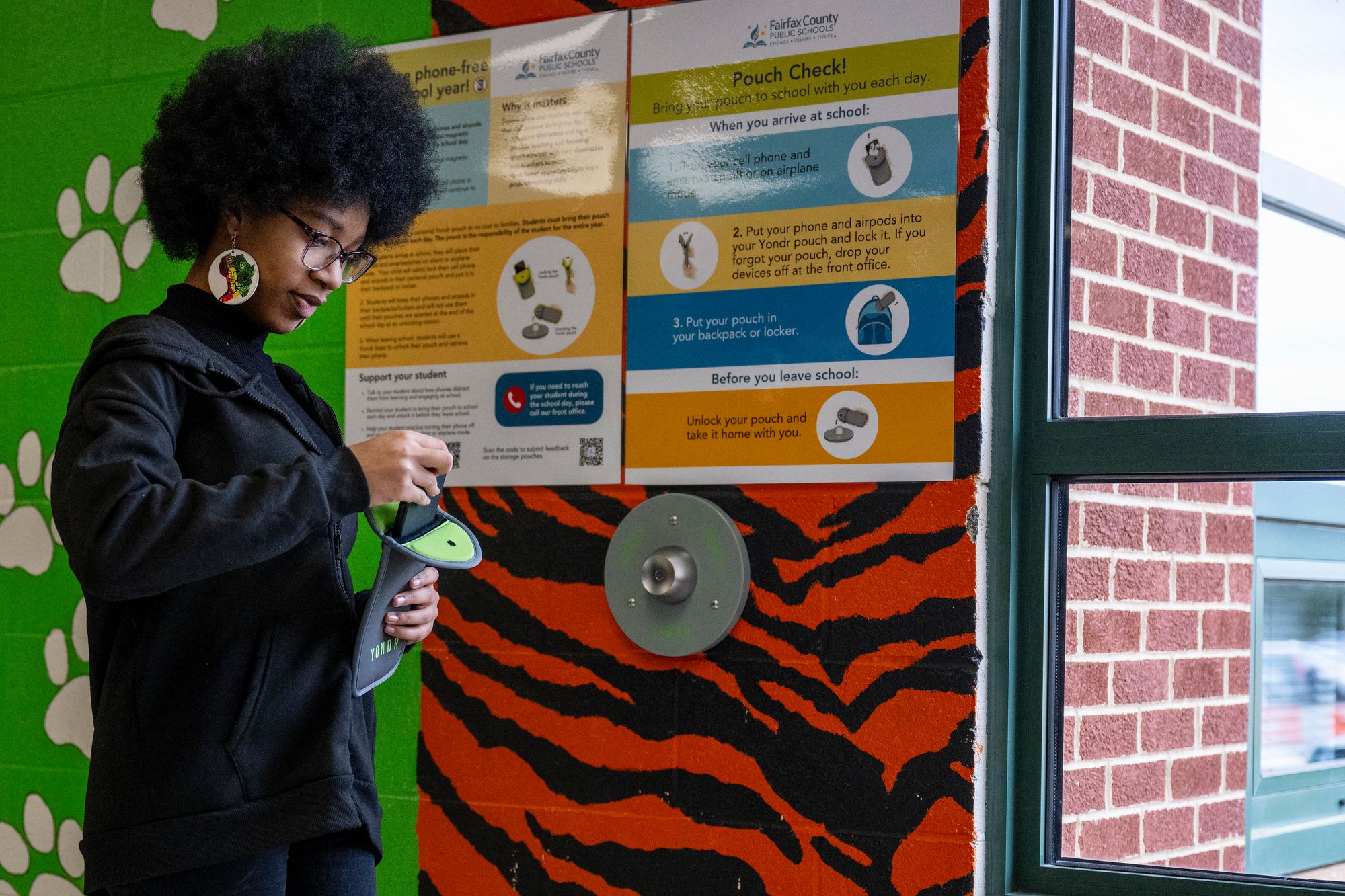

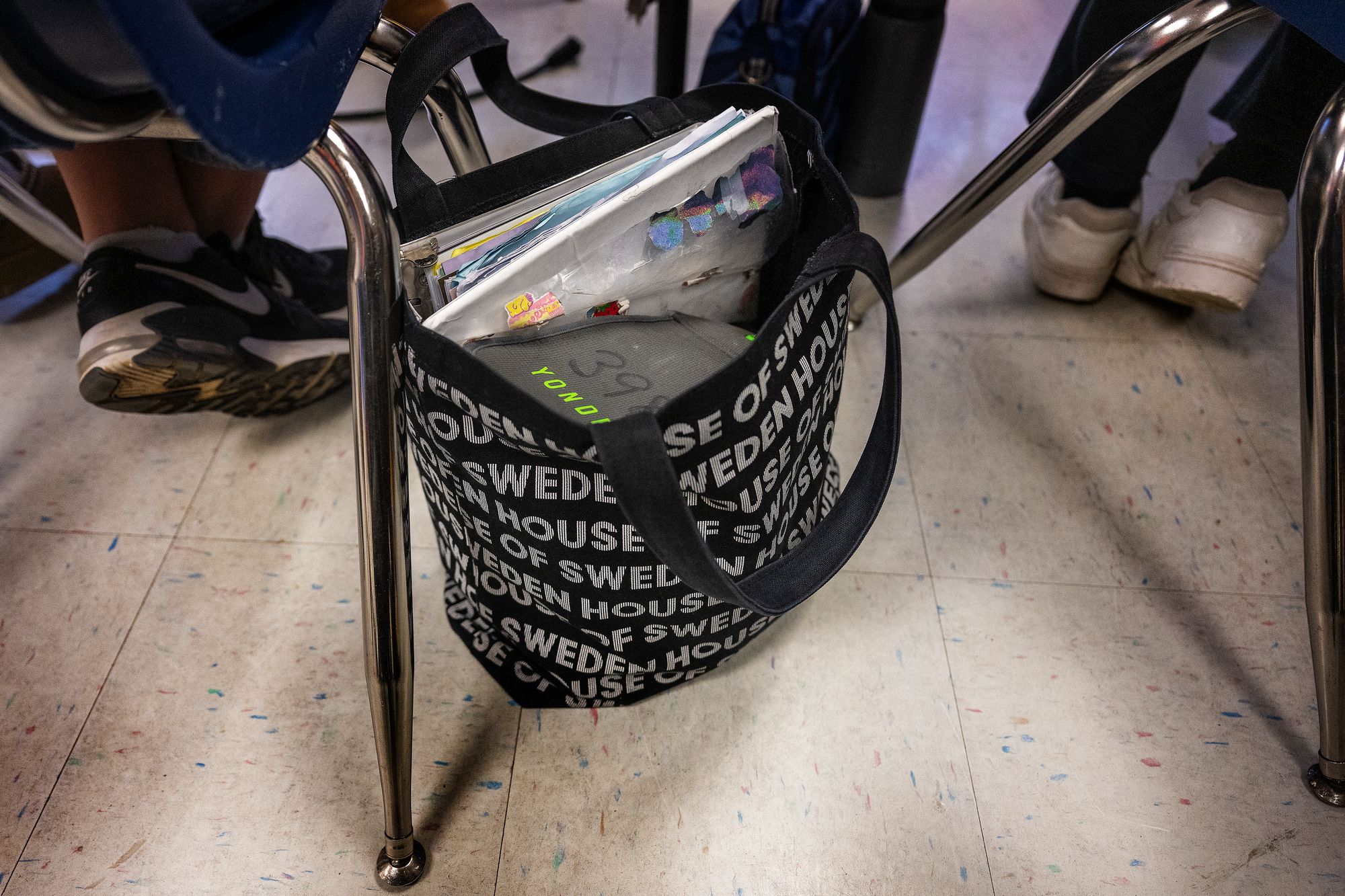

That is why many schools have opted to work with a company called Yondr, which says more than 2.5 million students are now using its lockable phone storage pouches. Students slip their phone inside the pouch when they arrive at school then keep it on them throughout their day, and are only able to unlock it later using a special magnetic tool.

"Our whole perspective is that it's not taking something away from students, it's giving them something back," Yondr CEO Graham Dugoni, who founded the firm in 2014, told CBS News.

Other schools use lower tech solutions: personal cubbies, students' lockers or even just a plain locked wooden box in every classroom. Some let older students to keep their phones, but require them to install app-blocking software.

According to the Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank, bans work better if teachers too are forced to ditch their devices.

Phone bans aren’t always popular with students. "I think it’s hurt me, because in times when I need to contact my parents or get any help, I’m being chased by people who believe the policy is a good thing," junior year student Mito Flores told Oregon broadcaster KOIN 6.

"While I see that there are positive sides to the policy, I think that it undermines student autonomy."

Others had more positive feelings, such as the New York 16-year-old who told Edutopia: "I got more work done today than I’ve gotten done for the last two weeks. I didn’t have to worry about my cell phone."

But many teachers who've implemented new policies say the difference is like night and day.

"The hallways buzz a lot more again. More students stop by my desk to chat — about history and their grades, sure, but also about their weekends, their lives," wrote New York City history teacher Sari Beth Rosenberg in an op-ed praising the city's smartphone ban.

"Students have not even complained much about the absence of their phones throughout the day. Instead, it feels like oxygen got pumped back into the building. And only now do we realize how flat things had become."

Will these bans actually work?

Both researchers voiced cautious optimism about the impact of these bans.

"We don’t know for sure yet, but early reports and testimonial evidence I have seen so far, including reports from teachers, parents and students themselves, suggest overall benefits from limiting or fully excluding smartphones from classrooms," says Robinson.

"I wish Congress and state legislatures would act to appropriately regulate digital media companies and their practices. If they did so, the burden would not fall on the shoulders of schools, teachers, parents and kids themselves. In that context, I support restricting smartphone use in schools."

Nagata similarly says the bans "could reduce distraction during instructional time" and "help protect attention for learning and in-person interaction."

However, he warns: "We still need more evidence on whether limits or bans actually work, especially in practice. Teens are often very tech-savvy and can find ways around restrictions, so the key question is not just if bans help, but how they are implemented and enforced."

Indeed, in Australia — which recently banned under-16s from social media — kids have found creative ways to get around the restrictions, such as commandeering their parents' old devices. Australian officials said this was only natural and did not undermine the ban as a whole, commenting: "We are not expecting flawlessness."

Some parents have also pushed back against school smartphone bans, particularly because they want to be in contact with their children if anything terrible happens during the school day.

Still, the momentum for such bans in the U.S. now seems unstoppable, and tech companies are not lobbying hard against them. According to Vaishnavi J, founder of the child safety consultancy Vys, these firms have been alarmed by calls to ban smartphones or social media for children entirely, not least because smartphones have enormous benefits to children (such as giving them a more private space to connect with peers and explore their identities).

By contrast, school bans are a much easier sell. "Industry recognizes that this is not a decision that they should have a say in," Vaishnavi J says. "This is about how school districts and governments and societies are structuring their offline environments."

Yet Vaishnavi J also notes that these policies leave a glaring hole for potential harm, via the very laptops and tablets that schools give to students to do their work.

Those devices, Vaishnavi J says, often have very crude limits and oversight methods which cannot account for unsafe content children might encounter through permitted video and social media platforms, discussions with AI chatbots or conversations with fellow students. That's especially true in cash-strapped school districts without the capacity to manage fleets of computers in detail.

"Phones are being completely banned for 10 hours of the day, and yet the school-issued devices can still become vectors of abuse, harassment, manipulation, addiction, dependency, despair," Vaishnavi J says. "I think there's a question about, well, how do we address that?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks