Secret Resistance figure who fought the Nazis and inspired brother’s timeless scent: The incredible story of the real Miss Dior

Catherine Dior, the sister of Christian Dior, was a crucial figure of the French Resistance. Clémence Michallon speaks to author Justine Picardie, whose new book provides an in-depth look at Catherine’s life and legacy

One day in November 1941, Catherine Dior went to buy a radio in Cannes.

The purchase was consequential: two years into World War II, France had fallen under German occupation. General Charles de Gaulle, a leader of the Resistance and future French president, was known to broadcast speeches from London, where he lived in exile. Owning a radio meant being able to listen to his addresses – and more generally to Radio Londres, a station operated from the BBC by members of the Resistance to their supporters in occupied France. In that radio shop, Catherine met Hervé des Charbonneries, an early member of the Resistance. The two fell in love, and by the end of the year, Catherine Dior – the sister of the illustrious fashion designer Christian Dior – had joined him in a Resistance network.

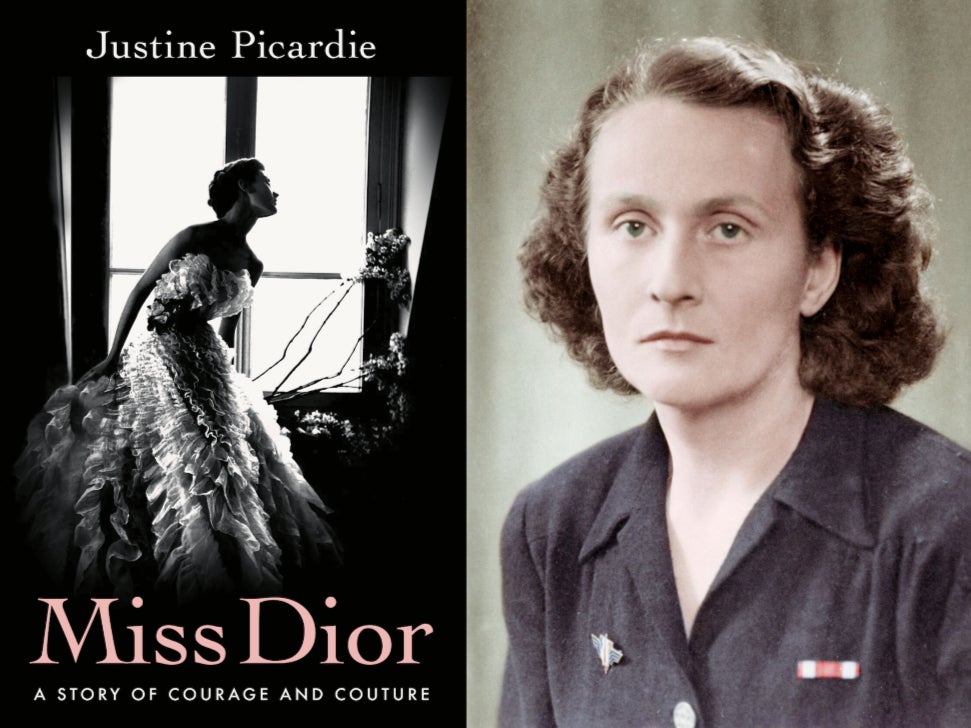

Catherine Dior would become a crucial figure of the French Resistance, arrested and tortured by the Gestapo in 1944 and sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp before her escape near Dresden in 1945. Her story, as British novelist and biographer Justine Picardie writes in a new book, is that of “a true heroine who exemplified the best and bravest spirit of French resistance during the war”. As Christian’s sister, she became the inspiration behind his famed fragrance Miss Dior, a heady, floral scent that remains a classic to this day. Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture, newly published at Faber & Faber in the UK and Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US, tells the story of Catherine’s life, caught between the atrocities of wartime and the glittery heritage of her brother’s fashion house.

Picardie, whose previous books include a biography of Coco Chanel, was invited by Dior to look at their archive, “perhaps with a view of doing a biography of Christian Dior”.

“I started looking at the archives, and there really wasn’t anything about Catherine in them at that point,” Picardie tells The Independent. “But when I’d found out the minimal information that there was about Catherine, I became really intrigued and fascinated by her story. I felt that in order to write about Christian, I needed to write about his relationship with Catherine.”

In the beginning, there were five Dior siblings: Christian, Catherine, Bernard, Raymond, and Jacqueline. Raymond, having served in World War One, never shook the trauma of combat, while Bernard struggled with symptoms of mental illness for years until he was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1932. Born on 2 August 1917, Catherine lost her mother, Madeleine Dior (to septicemia following an operation), at the age of 14. Her father, Maurice Dior, lost the family’s fortune in the Wall Street crash of 1929. The young Catherine, Picardie writes, “had no choice but to accompany her father on his downward spiral”, moving, unhappily so, from her grand childhood home in Normandy to a smaller farmhouse in Provence.

In 1936, Catherine and her brother Christian rejoined Paris together. Christian found work as a fashion designer, while Catherine sold hats and gloves at a boutique. Separated by 12 years in age, they remained “the closest of the Dior siblings”, Picardie writes. This brief period of carefreeness came to a “shuddering standstill” when Britain and France declared war with Germany on 3 September 1939. By the time Paris fell to Nazi occupation and France signed the Armistice of 22 June 1940 with Germany, Christian and Catherine had once again found themselves in Provence, selling vegetables at a market in Cannes twice a week.

It was the following year that Catherine met and fell in love with Hervé des Charbonneries, then a married man and a father of three. Catherine, a fervent supporter of De Gaulle, joined des Charbonneries in F2, a Resistance network with ties to British and Polish intelligence. “Her task,” Picardie writes, “was to gather” (under the code name of Caro) “and transmit information on the movements of German troops and warships, and, in order to do so, she made frequent and lengthy trips by bicycle to liaise with other F2 agents”. On one occasion, she hid “incriminating material” from the Gestapo during a raid, later earning praise for her “composure, decisiveness, and sang-froid”.

On the phone, Picardie acknowledges Catherine’s early knowledge of “trauma and disruption” in her childhood, which could have informed her temperament later on as a member of the Resistance. “But,” she adds, “it’s so hard to discover where people get courage from. All that is clear is that very few people had that courage when Catherine joined the Resistance. There were no more than 100,000 active members of the Resistance in a population of 40m. And even at its height, there were 400,000. That’s one per cent of the population. So people like Catherine were very, very unusual.”

When informants made it too dangerous to stay in Cannes, Catherine once again went to live with Christian in Paris, where she continued to work for F2. On 6 July 1944, she was arrested, forced into a car by four armed men. She was brutalised, tortured, imprisoned, and interrogated by the Gestapo. On 22 August 1944, she was deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp for women. The following month, she was transported to Torgau, a slave labour camp administered by the Buchenwald concentration camp. In October, Catherine was sent alongside 249 other French women to another site named Abteroda. Conditions, Picardie writes, were “dire”: “The women were expected to sleep on a cold cement floor, in the same building as a factory workshop. There were no latrines; rations were minimal (nothing more than watery soups and the occasional piece of dry bread).” Shifts, she writes, lasted for at least 12 hours. SS guards would beat them if they were deemed to be working too slowly. “They were also warned,” Picardie adds, “that anyone who refused to work would immediately be shot”. In early 1945, as the war entered its last month, Catherine was moved to yet another camp, this one in Markkleeberg, near Leipzig.

On 11 April 1945, US forces liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp. A few days later, on 15 April 1945, British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen. Allied forces were advancing in Europe; the liberation had begun. For prisoners, this meant being subjected to evacuation by SS officers. In recounting this time period, Picardie cites Holocaust survivor Zahava Szász Stessel, who once wrote that “evacuation turned out to be a euphemism for the death march”. The prisoners were made to walk despite exhaustion and illness, threatened by dogs and armed SS guards. It was during the march, on 21 April 1945, that Catherine escaped near Dresden.

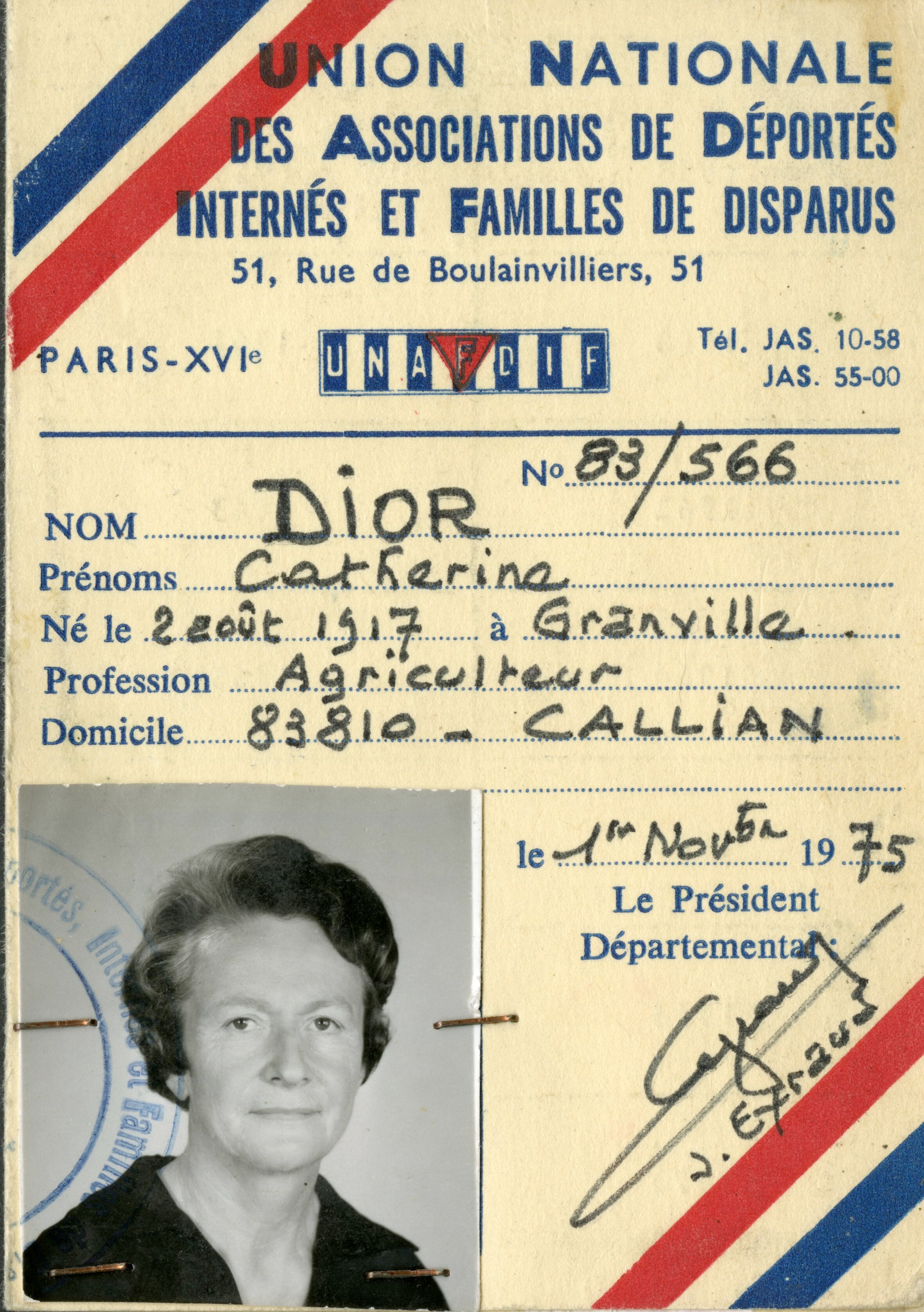

She made it back to Paris in late May 1945, so emaciated, Picardie writes, that Christian, who was waiting for her, failed to recognise her at first. Too sick to eat the dinner her brother had prepared, Catherine went to convalesce in Provence, and by autumn of 1945 returned to live with Christian and Hervé des Charbonneries in Paris. In France, she was awarded several decorations honouring her work as a member of the Resistance: the Croix de Guerre the Cross of the resistance volunteer combatant, and the Combatant’s Cross. She was also named a member of the Legion of Honour – France’s highest order of merit. Britain gave her the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom, recognising foreign nationals having aided Allied forces.

Catherine, who had inherited from her mother a passion for flowers, found work as a florist. Her medical records, according to Picardie, accounted for her trauma, both physical and mental. “Her innate modesty and quiet discretion were clad in the silence that surrounded her wartime suffering; her face still showed the sadness and pain that she had endured, and her body bore the scars of her torture and punishing imprisonment,” Picardie writes. “Instead, Catherine would become associated with the scent of Miss Dior, a perfume launched at the same time as the couture brand.”

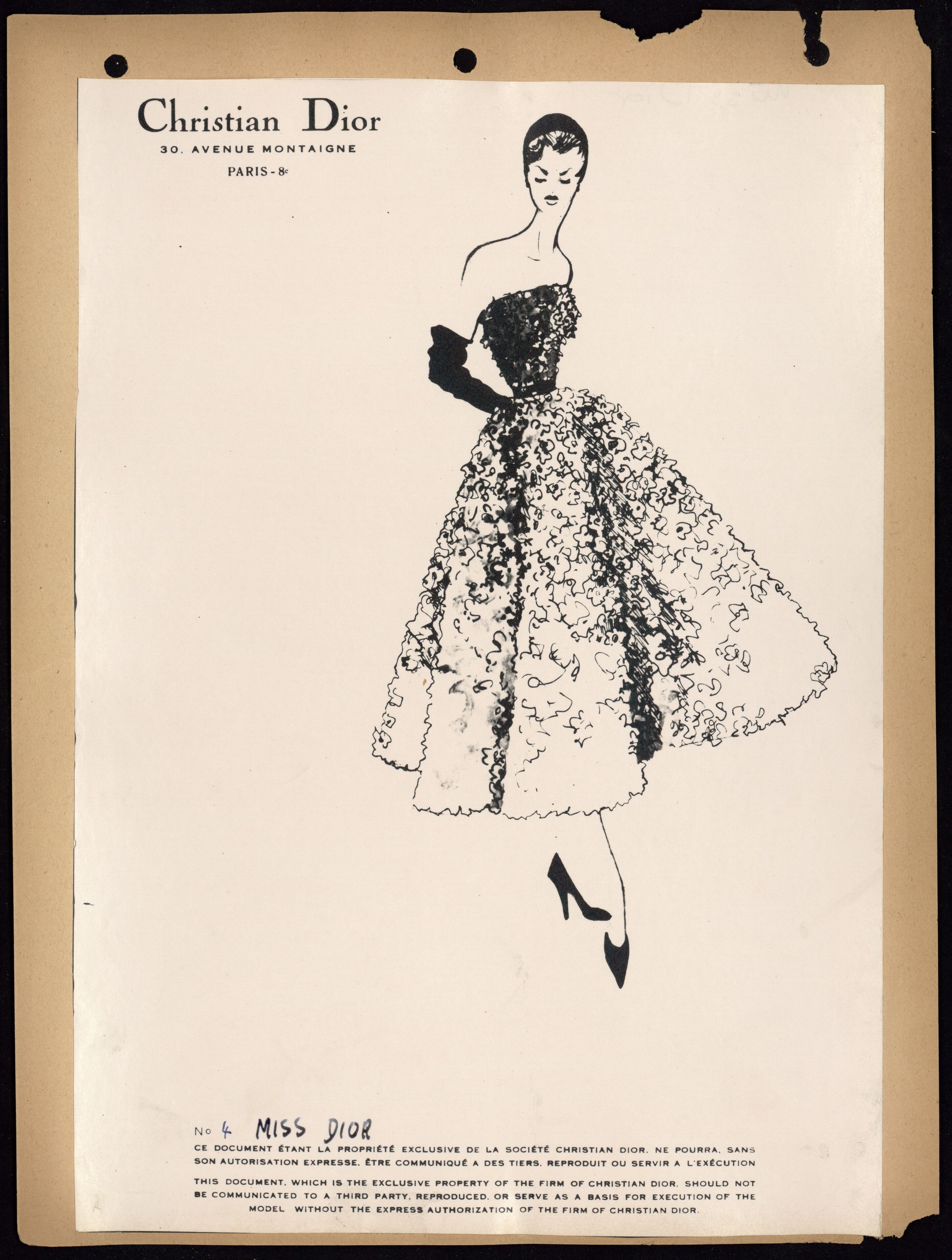

After his sister’s return, Christian Dior founded his own fashion house. He launched his first collection on 12 February 1947, in a salon sprayed with his Miss Dior fragrance. According to a Christian Dior confidante, the name of the perfume came from Catherine, somewhat accidentally. It is said that Christian was wondering what to name his fragrance when Catherine walked into the room, at which point Mitzah Bricard, one of Christian Dior’s close associates, is believed to have exclaimed: “Tiens, voilà Miss Dior!” And thus, a fragrance was born.

Seven years after her return to France, Catherine testified in the trial of 14 people charged with war crimes, including some who had tortured her in Paris and caused her deportation to Germany. As Picardie points out, she was only briefly mentioned in a report by the French daily newspaper Le Monde (without an acknowledgment of her connection to Christian Dior), and left out of other media reports.

Catherine died on 17 June 2008, having outlived both Christian (who died in 1957 aged 52) and Hervé des Charbonneries (who died in September 1989). Looking at the picture of Catherine’s life, Picardie is careful to underline Catherine’s own decisions, not defining her by the male figures in her existence.

“I think it’s important to say that her first act of Resistance was what led her to meeting Hervé,” she says. “So it wasn’t simply meeting Hervé that made her become a Resistant. By going to get a radio to listen to Charles De Gaulle’s banned broadcasts from London on the BBC, that in itself was an act of Resistance. If she’d been found with the radio listening to De Gaulle, she would have been arrested and imprisoned. She’d already shown that she had done that undertaking.”

Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture is published at Faber & Faber in the UK and Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks