Dallas police shootings: ‘In 1963, it was hard to accept that a nobody could accomplish something so grand – now it’s not so hard’

Pierce Allman was the first newsman to report on the Kennedy assassination. With last week’s bloodshed in Dallas drawing inevitable comparisons, he sees as many differences as similarities

As soon as it was reported that a sniper had opened fire in Dallas, the comparisons became unavoidable. Micah Johnson, the man believed to have shot dead five police officers and wounded seven more on Thursday night, launched his attack just yards from Dealey Plaza, where Lee Harvey Oswald shot President John F Kennedy in November 1963. The nearby memorial to the assassination remained taped off this weekend as part of the crime scene.

It wasn’t just commentators who heard echoes of 1963 in the reports of last week’s violence. As it emerged that Johnson, a black former Army reservist, had told police he wanted simply to “kill white people,” Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton invoked the bloodshed of half a century ago. “Dallas had a tragedy when President Kennedy was shot here in the 60s,” Paxton said. “And this is as close to that feeling, I think, as the city’s had in decades.”

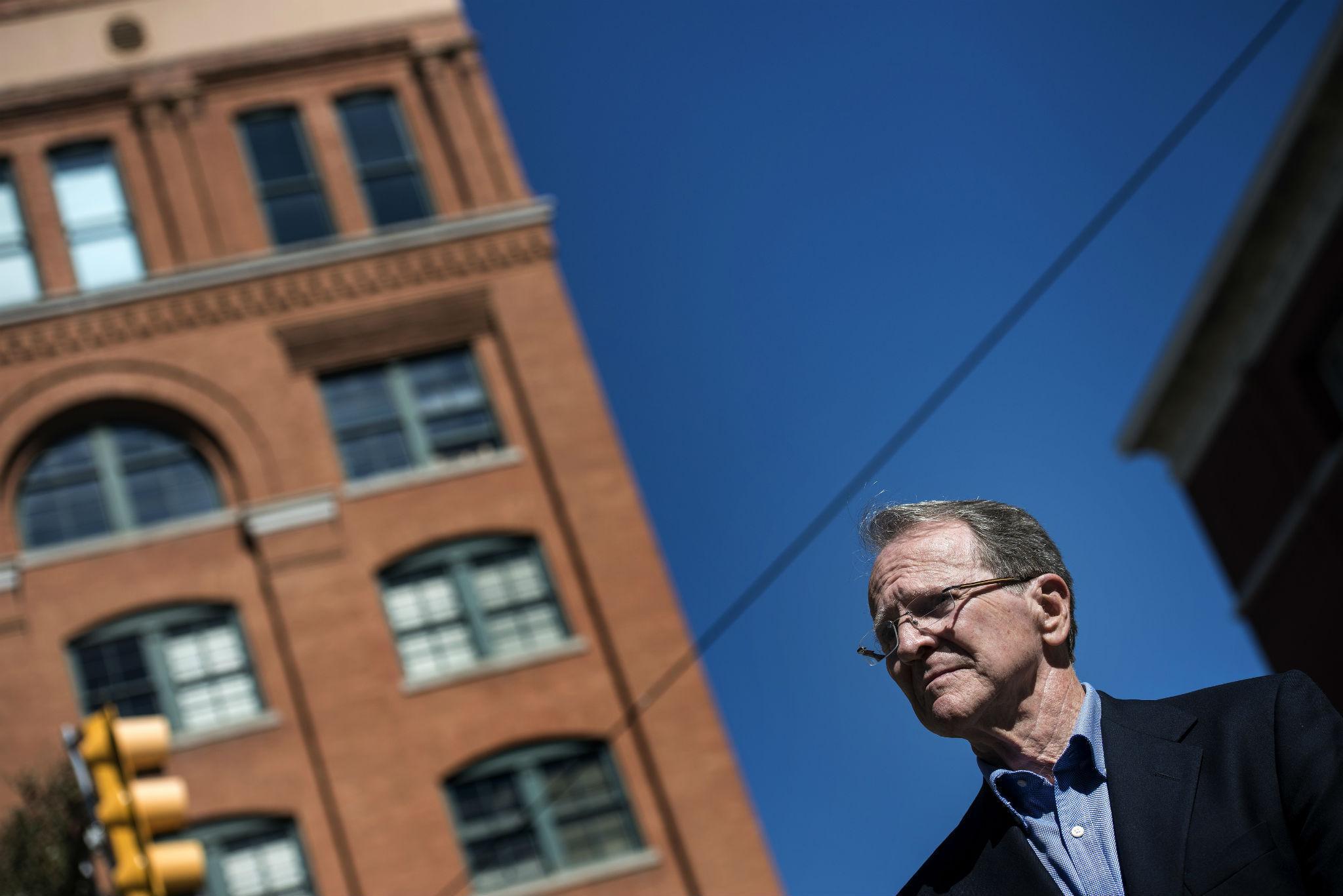

But to Pierce Allman, a lifelong Dallas native who witnessed the Kennedy assassination – and who was the first newsman to report from the scene in Dealey Plaza – there are as many differences between then and now as there are similarities. “The older generation may be harking back to November 1963,” Allman, who is 81, tells The Independent. “But I don’t think young people relate to it at all. To them, it’s just history.”

At the time of Kennedy’s murder, Allman recalls, “it was hard to accept that a nobody like Oswald could accomplish something so grand. But now it’s not so hard to believe that a warped gunman would go after people. Today, it’s ‘what’s this week’s tragedy?’ With the 24/7 news cycle and our limited attention spans, some people have already started to forget about Orlando. Right now it’s Dallas, but next week it could be Chicago or Cleveland or Baltimore.”

When the Kennedys planned their 1963 trip to Dallas, it was thought of as a crucible of right-wing extremism, the only city in Texas to have voted against the Democrat three years earlier. But they were greeted by cheering crowds of up to 200,000 people – a quarter of the city’s population at the time. “The assassination was a total juxtaposition to that mood: so wrenching, so sudden and so shocking,” Allman says. “It was a gut punch to Dallas.”

Then 29 and a reporter for local radio station WFAA, Allman was in Dealey Plaza to watch the First Couple’s motorcade come through. He heard the shots and Jackie’s screams, and then saw the car speed away. “I’m still amazed that it happened,” he says.

With the gunfire's echo still ringing around the plaza, Allman raced across the street to the Texas school book depository and asked a man emerging from the lobby where he could find a phone. The man, who Allman would later learn was Oswald, pointed inside. Allman called the radio station and became the sole journalist to report from the scene, staying on the line for 45 minutes, relaying developments as Oswald’s rifle and shell casings were found upstairs.

For all the talk of Cold War conspiracies – talk that persists to this day – investigators soon concluded that Oswald had acted alone. The same may yet turn out to be true of Johnson. “My impression has always been that Oswald just wanted to be somebody, to do something,” Allman says. “This was what he chose, and circumstances played into his hands.”

Allman left WFAA in 1965 and went on to enjoy a successful career in marketing, PR and property. The Kennedy assassination was perhaps the first major breaking news story to be played out live on TV and radio, and he had grown increasingly dismayed by the conduct of his fellow reporters. “It was a feeding frenzy,” he says, “and a new paradigm evolved from it.”

The legacy of the assassination is still felt today, not least in the news coverage of dramatic events such as last week's attack. “The 24/7 news cycle has so many effects,” Allman says. “When you have that much time to fill on thousands of news channels, you begin each hour with the facts – but by the end of the hour, where are you? The more disproportionately things are reported, the more some tortured soul out there might be watching and thinking, ‘I could have my 15 minutes’.”

In 2016, a speculative tweet might be reported by a major news network. In 1963, Allman held himself to a higher standard. “When I first went on the air, I didn’t say, ‘The President has been shot, it looks like he’s been killed.’ That would have been irresponsible. I didn’t know his condition at the time. So at first I just said that three loud explosions had been heard, and that we couldn’t confirm whether the President had been hit.”

Dallas retained the stigma of the assassination for several years, earning itself the sobriquet “City of Hate”. Allman says: “First the President is killed, then the assassin is caught – and then 24 hours later the assassin is killed. If you were an outsider, you were looking at this city and thinking, ‘what is wrong with you people?’ For about five years, I would tell people I was from Dallas and they’d say, ‘oh, you’re the guys that killed Kennedy’.”

Speaking after this week’s shootings, Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings reflected: “For years, people around the world saw our city through the lens of the Kennedy assassination, [but] those of us who love this city always knew there was so much more to Dallas than what happened on that day in 1963.”

The cloud of negative associations cast by Kennedy’s death was at last dispelled in 1972, when the Dallas Cowboys won their first Super Bowl. Today Dallas is one of the fastest-growing urban areas in the US and, Allman believes, far less fraught with racial tension than many other major American cities. “We’ve got problems, like any city,” he says. “But Dallas is a good place.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks