‘Countless red flags’: Report reveals years of warnings before 5-year-old Oakley Carlson vanished

The last confirmed sighting of Oakley Carlson was in February 2021. She was declared dead in July 2025

A newly released state report details years of missed warning signs, repeated child abuse and neglect complaints in the case of Oakley Carlson, a five-year-old girl who disappeared from her Washington home in 2021.

The child fatality review, published by the Washington Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF), documents at least 14 referrals to Child Protective Services involving Oakley’s family and raises questions about whether the girl was returned to her biological parents too quickly despite ongoing safety concerns.

Oakley was last seen by someone outside her family in February 2021. Authorities were not alerted that she was missing until nine months later, in December 2021.

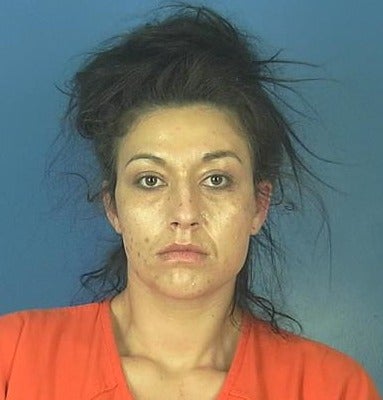

Andrew Carlson and Jordan Bowers were never charged for Oakley’s disappearance or presumed death, but law enforcement has since maintained that they are persons of interest in the case.

In July 2025, Oakley was declared dead, which triggered a legally required review of how caseworkers responded to allegations of abuse and neglect.

For Oakley’s former foster mother, Jamie Jo Hiles, the new report confirmed her worst fears about how the case has been handled, she told The Seattle Times.

“I mean, honestly, when I read through it, it was just disheartening to read the countless red flags that were presented in regards to Oakley and her siblings,” Hiles said.

Oakley lived with Hiles from about nine months old until just before her third birthday, when she was returned to Carlson and Bowers.

“DCYF just lets kids fall through the cracks,” Hiles added.

What happened to Oakley?

The search for Oakley began on December 6, 2021, when a school principal requested a welfare check after discovering that she had not attended school for an extended period of time and that her older sister made alarming statements during a sleepover.

“She said that ‘Oakley is no more’ and that ‘there is no Oakley,’” according to an affidavit obtained by KCPQ.

In a later interview with a child advocate, Oakley’s sister reportedly said “her mother Jordan had told her not to talk about Oakley” and that Oakley “had gone out into the woods and had been eaten by wolves.”

Oakley’s nine-year-old brother told detectives that Bowers would “put Oakley in the closet, possibly under a stairwell,” and that he “witnessed Jordan beat Oakley with a belt and has been worried about her starving.”

Carlson and Bowers told investigators the last time they saw Oakley alive was November 30, 2021. Authorities, however, found no evidence that she was alive after a house fire on November 6 that displaced the family.

Carlson claimed it was Oakley who started the fire by lighting a couch. But investigators have not determined whether Oakley was alive before or after the fire.

Hiles said she warned the agency after learning about the fire.

“I sent an email to Oakley’s caseworker and I said, ‘hey, this is not normal, this not safe, and I’m letting you know now that if something happens to these kids that you have been forewarned,” Hiles said. “When you send a child back from foster care and a mandated reporter calls, you listen to that call. You don’t screen that out.”

Despite three reports that cited a house fire and unsafe living conditions, DCYF determined the allegations did not meet the legal standard for intervention.

In December 2021, law enforcement declared Oakley missing and placed her siblings into protective custody. Carlson and Bowers were arrested for obstructing an investigation.

Both were later convicted of drug-related child endangerment charges involving other children. Bowers was released from prison in the fall after serving time on a separate charge.

Neither parent has been charged in Oakley’s disappearance.

A long trail of CPS reports

According to the report, DCYF received at least 14 referrals about the family, some predating Oakley’s birth in 2016.

Between 2013 and 2014, five reports involved Bowers, her partner and Oakley’s half-sibling. That child was briefly placed out of the home and later returned.

In 2017, CPS received allegations that Bowers yelled profanities at a 17-month-old sibling and failed to provide necessary medical care. That report was closed for not meeting the legal threshold for intervention.

A month later, another caller raised similar concerns and alleged drug use and domestic violence. A CPS investigation followed, and DCYF filed dependency petitions for Oakley and her siblings. Law enforcement removed the children from the home.

In January 2018, the court declared the children dependent after the parents failed to appear at a hearing. DCYF later sought to terminate parental rights.

After that filing, Carlson and Bowers began completing court-ordered services – parenting classes, substance-use treatment and psychological evaluations. Carlson, however, was “discharged from domestic violence treatment due to non-compliance.”

DCYF said a judge granted Bowers’ appeal, and the termination case never went to trial. In 2019, a caseworker and a court-appointed advocate asked to change the plan to adoption for Oakley. The court denied the request.

That fall, DCYF began allowing unsupervised visits. A caseworker documented that Oakley appeared to be doing well and made no concerning disclosures. The court approved a trial return home with regular monitoring.

“My husband and I were over the moon excited to adopt Oakley, then months later, to be told, ‘just kidding, she’s returning home next month,’ blows my mind,” Hiles said about her time with Oakley.

“They still return the kids home even though the report says that he just wasn’t doing what he was supposed to be doing for his substance abuse classes and his domestic violence classes. Do we think that’s okay?” Hiles continued.

Then the pandemic hit. Gov. Jay Inslee ordered safety visits to be conducted virtually. In June 2020, the court dismissed Oakley’s dependency case, ending DCYF supervision.

The last visit

In January 2021, DCYF received a report that Oakley had scratches and bruises on her face around Christmas, with the person reporting that they heard screaming from the home.

When a DCYF caseworker tried to visit the home, they noted that Bowers would not let them in because she ”was afraid of CPS.”

The caseworker briefly saw Oakley through a sliding glass door, wearing only a diaper, and did not observe visible injuries.

“In the report, it does say like, ‘We have no legal right to go in and search a house,’” Hiles said, “But, don’t you think you should have followed up a little bit more on that?”

A school principal then did a welfare check on February 10, 2021, but did not see Oakley. A caseworker checked again on March 8, 2021, but was refused entry by Bowers, who said she “would not answer any questions without an attorney present.”

That was the final documented in-person contact with Oakley by a caseworker.

For Hiles, reading that account in the report was devastating and said it “made me sick to my stomach.”

“I thought, ‘That’s it. That’s all you did to check on her ... That’s the last time my baby was OK.’”

The report notes that there should have been more of an effort in the January 2021 visit to interview Oakley’s siblings and relatives and notes there are areas for improvement, but a DCYF spokesperson told KIRO7, “Any identified improvement opportunities are not intended to suggest a direct correlation with the presumed fatality in this case. Improvement opportunities are defined as the gap between what the family needed and what they received from the child welfare system.”

“This whole write-up to me felt like an applause for DCYF and how they handled everything like, ‘you know what, you did the best you could with what you had.’” Hiles said, “Like what a slap in the face to those kids.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks