‘I had nowhere to go’: The poverty-stricken Brazilians hit the hardest by Bolsonaro’s pandemic response

Makeshift encampments are popping up across the country as thousands become stranded — and the president is only making matters worse, writes Terrence McCoy

Not yet able to face her new life here, she kept her eyes closed. The morning was still too cold, too dark. At her side, beneath a roof of black plastic, slept a young family she scarcely knew. They’d been together here for weeks, economic refugees of the coronavirus pandemic, unemployed and evicted, now clustering together to hope for better days to come.

The sky cleared. Zuleide da Conceicao Felix, 67, stepped out of her barren shack on the outskirts of metropolitan Sao Paulo. She made coffee on her stove – a cherished relic of her old life – and tried to ignore the chill. An illiterate maid, Felix had led a life of poverty, working the past few years for £170 per month. But even she’d never been through anything like this.

“My husband and I had a bedroom,” she reminisced. “We had had a living room. We had a television. A kitchen. It was everything that we needed.”

She looked at the ground.

“Now we’re here.”

Here: A collection of shacks built on the trash-strewn remains of a bankrupted factory, cut off from public transportation, with neither running water nor a market – one more new settlement in a profusion of sprawling communities now being settled by Brazilians left homeless by an outbreak that refuses to relent.

These are the people President Jair Bolsonaro said he wanted to protect when he adopted the unorthodox pandemic strategy of doing little to control the spread of the coronavirus. In the face of one of the world’s worst outbreaks, he has undercut nearly every containment measure proposed by federal and state officials by appealing to the needs of poor, working-class Brazilians. They couldn’t stay home, he said. They had to work to survive.

“Hunger is killing many more people than the virus itself,” he said in March. “We have to face the reality. It’s no use to run away from what is there.”

But rather than helping the most vulnerable, economists say, Bolsonaro’s fatalistic approach has only prolonged the crisis – and driven more people into poverty.

Nearly one in five Brazilians say they’ve been stranded without any income. Half of the country is struggling to put food on the table. Nineteen million say they're going hungry. The unemployment and inequality rates are at record highs. After the government reduced a program of pandemic payments to the poorest Brazilians, the largest number of Brazilians in a decade tumbled into extreme poverty, living on less than £1.40 per day. The homeless population swelled.

“When people are scared of getting sick, and when people are getting sick on the scale that they are in Brazil, there’s going to be a lot of instability,” says Marcelo Neri, an economist at the Getulio Vargas Foundation, a university in Rio de Janeiro. “This has been terrible for the economy, especially for informal workers.”

Brazil has now been left with the worst of both worlds: A half-million dead – more than anywhere outside the United States – and millions more without work.

One of those left jobless was Felix. She was told by her elderly boss to stop coming to clean her home after the virus arrived. The older woman worried that Felix would bring in the disease from the crowded buses she rode to work.

I'll call you when things get better, the woman promised Felix.

That was 15 months ago. Things never got better. The virus continues to rip through Brazil. And Felix - who ran out of savings, went three months without paying rent, got evicted and now lives here among what’s left of her possessions – is still waiting for that call.

The tent cities spring up in a matter of hours.

One spilled onto the church grounds of a famous televangelist. Another took root on land owned by the state oil company. In Sao Paulo, the largest city in the Western hemisphere, more than 800 families poured into a vacant shipping container yard. Six hundred more signed up for space on an empty field beside a favela.

The communities, populated largely by people who’ve lost job and home, have come to symbolise the government’s failure to buffer its poorest citizens from the economic impact of the pandemic. It extended £90 monthly emergency payments to millions of needy people – lifting some families out of poverty, temporarily – but that program was reduced in September, then suspended for months. The government did not prohibit evictions, as did the US, nor incentivised the hiring of vulnerable young poor people, as did the UK.

“What has Bolsonaro done to save the economy?” asks Lena Lavinas, an economist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “The only thing that he did was to say, ‘Nothing can stop.’ This isn’t a proposal to save the economy.”

Bolsonaro’s office did not respond to a request for comment. In public, the president has fretted about government debt. When asked whether he should be doing more to alleviate the suffering, he has expressed irritation. “What country in the world has done what we did, with the emergency payments?” he asked. “And still they are criticising, saying they want more.”

The new settlements, many founded after the payments were reduced, are now feeding into one of Brazil's most protracted and polarising debates. A country of vast unused spaces and inescapable inequality, Brazil has long been a theatre of bitter land disputes between landowners and squatters with nowhere else to go. Many of the irregular enclaves, which now house millions, live under constant threat of removal.

During the pandemic, as people were expelled onto the streets and the settlements multiplied, authorities stepped up removal operations. In Sao Paulo, they cleared out nearly 4,000 people – the most in Brazil. An additional 3,000 were removed in Manaus, the Amazonian city devastated by the virus. The Brazilian supreme court this month suspended the removals until the end of the year, angering Bolsonaro, a fierce defender of landowners.

“It's the end of private property,” he declares. “What a terrible decision.”

But settlements most often take shape on vacant land – which was exactly how a desolate stretch beside an industrial yard in northern Sao Paulo looked to maid Janeide Pereira. She was walking outside her building last June, frantic. She had lost her job. The mother she worked for had said she wanted to protect her children from possible exposure to the virus. Now Pereira was about to lose her home, too.

“I had nowhere to go,” she says.

This dusty plot where people fly kites and throw rubbish looked like her best option. She dragged out her possessions, strung up a black plastic tarp and set up a new home for her five children. Within hours, she had neighbours. They filled every corner of the city-owned lot. Small wood houses soon rose. Running water and electricity was set up by cutting into nearby lines. The settlement of Jardim Julieta was born.

The people who arrive now, some with injuries from life on the streets, are grudgingly turned away: The community is full. Encampment leaders tell them of another place, five miles to the north. There, on the forested grounds of a bankrupt factory, another settlement is forming.

And so that was where Felix went.

“Agua!” came a shout in the distance. “Agua!”

Felix craned her head and rose. The community had run out of water the night before. All morning there had been fear that the city water man, who had been filling their 2,000l cistern off the books, had forgotten them.

Felix’s husband pulled out several empty buckets. He handed one to her, and, giggling, off they went, stepping across the rubble and trash that construction companies had left here. They found the water man at the front of the community.

“Agua!” Felix yelled with delight.

She was trying to be happy here. But more and more she was feeling her 67 years. Her body was aching. She was diabetic. And there was so much uncertainty to life in the settlement. The water could stop. People could forget to send them the food donations on which they survive. One day had brought a young family with three small children – one of the 250 families now crowding the settlement – and now they’re all sharing her shack and one lightbulb.

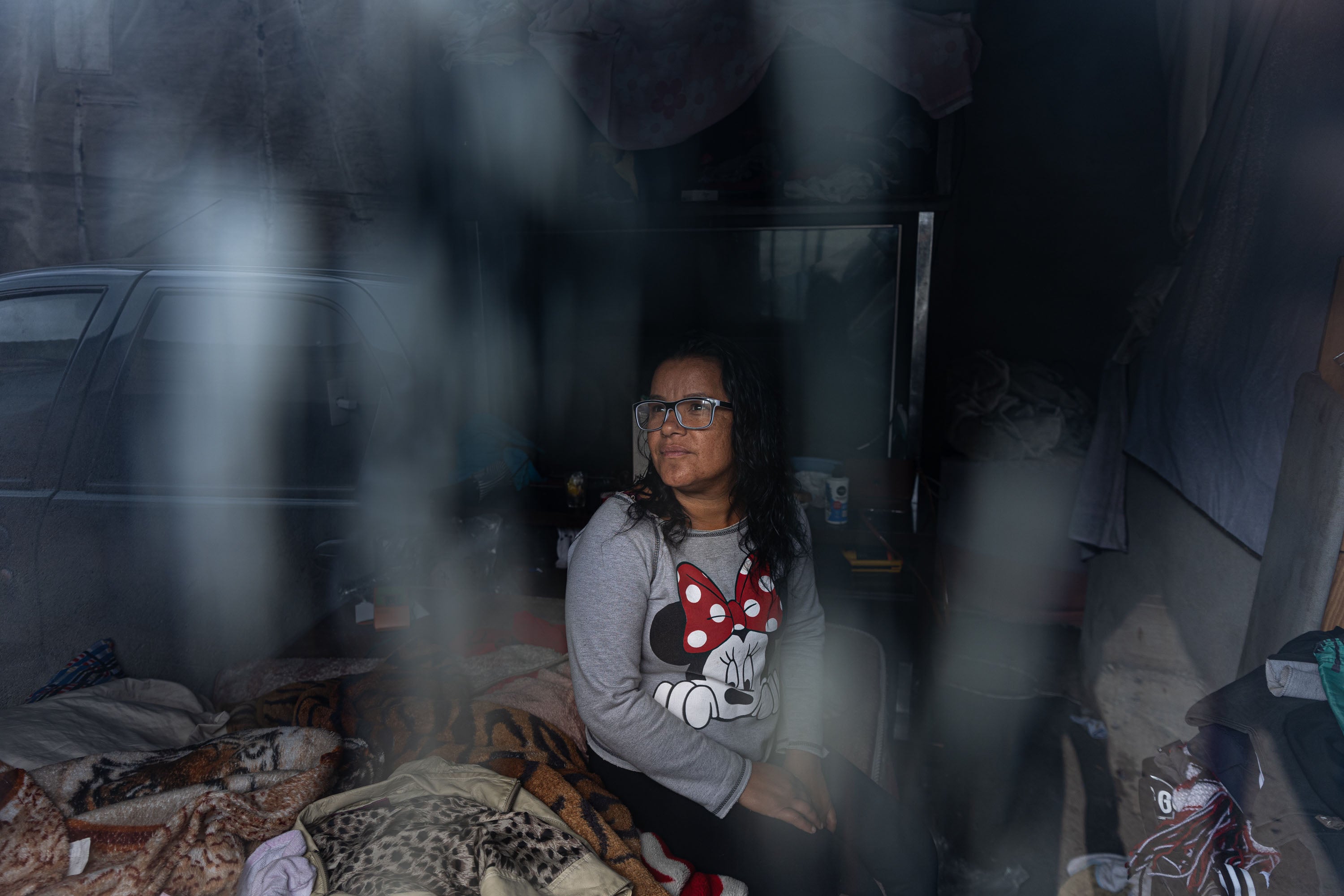

“We were evicted,” says Andreia Rodrigues de Oliveira, 36, the mother. “Three nights we spent sleeping under a store awning before hearing of this settlement.”

Every day Felix waits. When she was about to lose her home, she called her boss. The woman - “really good people,” Felix says – bought her a tank of gas and reminded her she’d be in touch when the pandemic passed. But then Felix moved out here, where her phone can’t get a signal, and she realised that if her boss did call, she wouldn’t know.

She reached the community faucet and watched the water gush into the buckets. She hefted them with a grunt and made her way back to her shack. Things would get better, she reminded herself. The pandemic would pass. Her boss would maybe call her daughter, her daughter would find her here, and Felix would go back to work.

She set down the water. She looked at her new home. She thanked God for what she had. The water had arrived today. And, looking out into the distance at the families all around, she knew she would not be alone. Nearly 400 more were expected to arrive in the coming days.

“Every day there are more,” she said.

The Washington Post’s Heloisa Traiano contributed to this report.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks