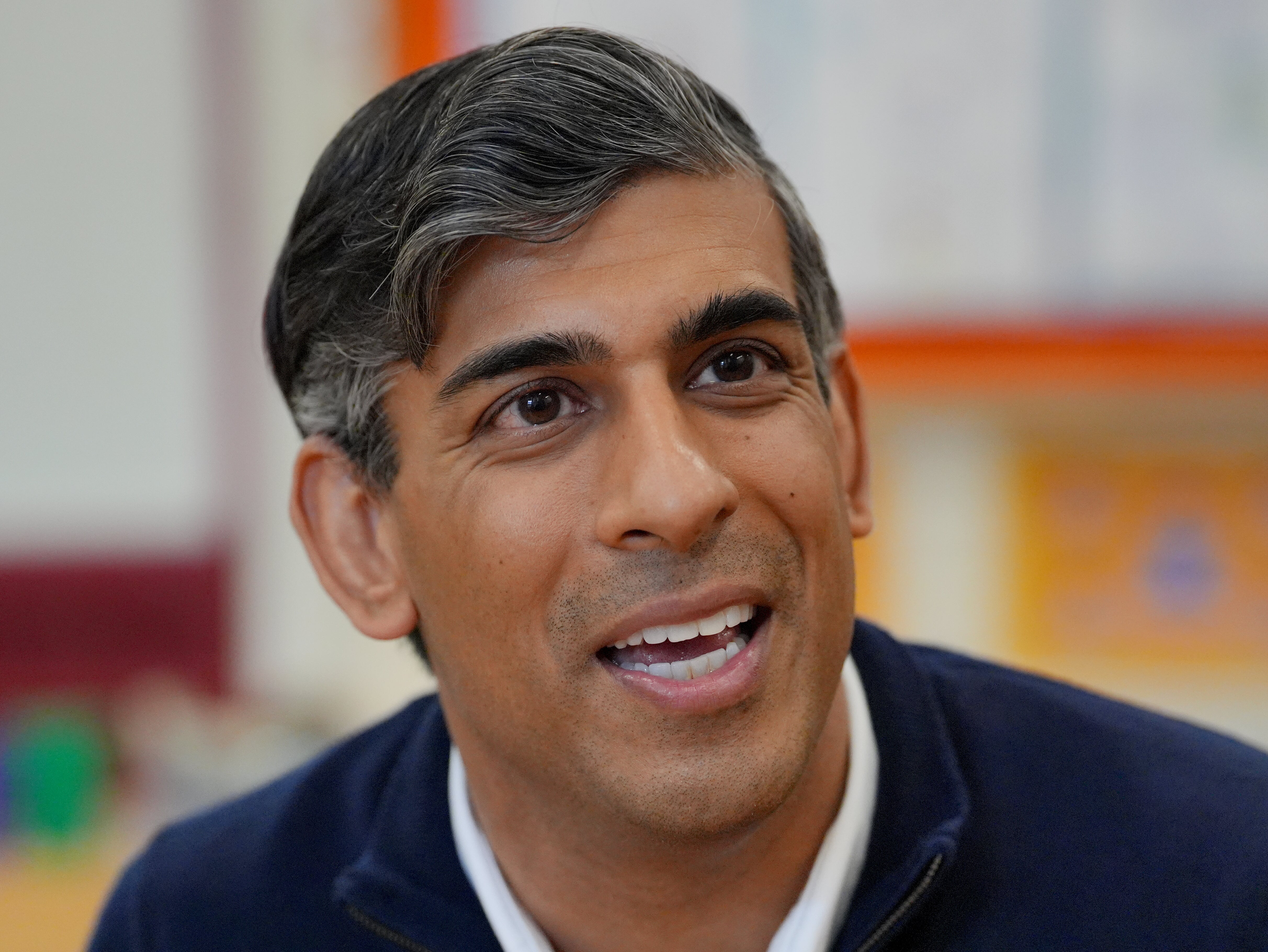

Life after power: What do former prime ministers do all day?

Rishi Sunak has taken a job at Goldman Sachs. But how have other past Downing Street residents spent their time since leaving office? John Rentoul takes a look

Rishi Sunak, who is only 45, has said he will give his salary from Goldman Sachs to charity. As the richest MP to become prime minister since Earl Derby in the 1850s, he can afford to do so, but in fact no recent prime minister has needed the money, and all of them have tried in other ways to remain relevant.

Sunak seems less desperate than most of his predecessors to make a mark in his post-prime-ministerial career – and it should be noted that, despite persistent speculation when he was in No 10 that he would be off to California the moment the election was over, he is still here.

Other recent prime ministers have tried harder to keep their hand on the steering wheel after leaving office...

Margaret Thatcher: divisive icon

A book to be published next week by Peter Just, Margaret Thatcher: Life After Downing Street, claims that she enjoyed “perhaps one of the most consequential political afterlives in British history”.

Her afterlife, however, was mostly the afterburn of her ideologically driven premiership and the way she was deposed, which created an instant myth of betrayal and divided the Conservative Party, increasingly on the issue of Europe, for two decades.

She did not take on other jobs after she left No 10, partly because she was already of retirement age, leaving office at the age of 65. She became the first prime minister to set up a foundation, funded by admirers who wanted to perpetuate her legacy. The Thatcher Foundation’s online archive is one of the best historical resources of the period.

John Major: national treasure (eventually)

John Major went off to watch cricket on the day he left office, and took a number of well-paid directorships. He kept a low profile for many years, apart from a role as guardian to Princes William and Harry after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997.

He was bruised by his defeat at the hands of Tony Blair, but gradually reinvented himself as a font of moderate Tory wisdom and indeed of standards in public life, which is ironic for a prime minister who lost power in a welter of sexual and financial scandal.

Tony Blair: another divisive icon

Tony Blair took a very different approach, setting up three foundations (later merged into the single Tony Blair Institute for Global Change) and earning money to pay for them. While he stayed out of British politics to avoid being blamed for the failures of his successor, his work abroad seemed calculated to annoy his many haters.

British public opinion remained so hostile to him that he felt he had to donate the £4m advance for his memoir, published in 2010, to the Royal British Legion. The public part of his work, trying to build the economy and state capacity of the Palestinian occupied territories, came to nothing.

But he too gradually rehabilitated himself, after Nick Clegg became liberal opinion’s public enemy number one for betraying his tuition fees pledge. Blair became more popular as the best advocate of the pro-EU case in the 2016 referendum and the aftermath.

His institute is now established as a powerful think tank in British politics and a successful consultancy in the art of government abroad.

Gordon Brown: good works

Blair’s successor has tried to be as different from him as possible, basing himself in Scotland and devoting himself to charity work. He carried out an inquiry for Keir Starmer into what to do with the House of Lords, remodelling it as an Assembly of the Nations and Regions. This failed to make it into Labour’s election manifesto last year, which said: “Labour is committed to replacing the House of Lords with an alternative second chamber that is more representative of the regions and nations.” But it did not say when.

David Cameron: back as foreign secretary

David Cameron thought he would stick around in the House of Commons and offer Theresa May’s government the benefit of his experience. Blair’s departure from parliament on the day he stepped down as prime minister was widely disapproved of, but Cameron quickly realised that Blair was right, and it would be better for the party if he cleared off.

Of all former prime ministers, he got into the most trouble with his business interests after Downing Street, lobbying for a company called Greensill.

However, he came back to government seven years after stepping down to try to bolster Sunak’s failing government as foreign secretary. This was an appointment from an earlier age – Alec Douglas-Home returned as foreign secretary in Edward Heath’s government in the 1970s. In Cameron’s case, it didn’t help.

Theresa May: dutiful after the end

Theresa May stayed in the House of Commons, becoming an increasingly waspish commentator on her successor’s government. Her memoir – all former prime ministers have written them, even Liz Truss – was less of an autobiography and more of a political book with the curious title The Abuse of Power. This sounded as if she was railing against the system of which she had been in charge, but it was really about pursuing her campaigns against modern slavery and violence against women (the subtitle was Confronting Injustice in Public Life).

Boris Johnson: ‘I’m still here’

Johnson scuttled out of the Commons rather than fight a by-election that he could have won, after he was found to have deliberately misled parliament over lockdown parties. He wrote a hurried memoir, but there is still no sign of his book about William Shakespeare.

He appears to think that the Conservative Party might still turn to him to rescue it – oblivious to his responsibility for allowing immigration to quadruple, which is the one issue on which former Tory voters feel most betrayed.

Liz Truss: ‘I was right’

Truss has tried to associate herself with the Trumpian movement in America, but her prime-ministerial afterlife has been shorter than her 49 days in office. Her main preoccupation seems to be telling people on X/Twitter that she was right, that she was the victim of a conspiracy by the Bank of England, and that Rachel Reeves is doing a worse job than she and Kwasi Kwarteng did.

Her main role has been to act as Labour propaganda; her main impact has been to surprise people by appearing with other former prime ministers at the Cenotaph.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments.png?quality=75&width=230&crop=3%3A2%2Csmart&auto=webp)

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks