As Peter Mandelson’s biographer, I know how his mind works – and why Epstein was his weakness

The Epstein files reveal not just a catastrophic breach of trust, but the final act in a long political psychodrama. Donald Macintyre reveals how a man so adept at managing risk came to take one that could destroy a government – not to mention his own career – and says the answers lie deep in a life shaped by a fatal attraction to wealth and influence

The consequences of Peter Mandelson’s covert and corrupt association with the disgraced sex-trafficker Jeffrey Epstein – the future of Keir Starmer’s premiership being foremost among them – are so monumental that both the friends who knew Mandelson at his best, and the enemies who knew him at his worst, have been left reeling and asking, “How could he do it?” Few ever imagined that even the so-called Prince of Darkness could, or ever would, act quite as treacherously as has been revealed in the Epstein files released last week.

What has been equally hard to fathom is that Mandelson took, and clung on to, his Washington job even though he must have known that his cover had every chance of being blown. And even when it was, he still fought to keep that role until it became unsustainable, just as he did with his friendship with Epstein.

So, to the other question everyone is asking: what on earth was he thinking?

Only his psychologist would be able to give a clear diagnosis of what exactly was going on inside his head, but as his biographer, I can say that his lifelong tendency to live beyond his means, and his proclivity for taking risks – personal as well as political – are both clearly there. And the clues as to why lurk deep in his pre-Epstein past.

A sense of entitlement

Unlike Starmer, Mandelson arrived on the world stage with a political pedigree. Mandelson was born into the Labour Party, the grandson of Herbert Morrison, a Labour titan who was once the party’s deputy leader. His parents knew Harold and Mary Wilson quite well, as their neighbours in Hampstead Garden Suburb, and one of his most lasting childhood memories was of watching Harold Wilson being driven off to Downing Street after the 1964 election. Soon after, he would actually sit at the cabinet table, when the family were invited to a reception by the newly elected prime minister.

Mandelson’s mother recalled that he had been “political from the age of five”, and Morrison fascinated him. He would frequently – and proudly – mention him, especially in his early political career. While Morrison did not visit the family home frequently, on one occasion when he did, Mary Mandelson recalled the young Peter returning from school, finding that Morrison had popped by when he was not there, and bursting into tears. This all gave him a tribal sense of being Labour, of course, but it also meant that, unlike many children who grew up in the Fifties, he connected the party with political power.

On the face of it, until his early forties, Mandelson was ambitious but not obviously greedy. His early career was if anything rather earnest, at least before it became high-profile: VSO in Tanzania as an energetic volunteer before Oxford; work as a junior official in the TUC; researcher to the Labour minister Albert Booth; Lambeth Labour councillor; first a researcher, and then a producer, at London Weekend Television; and then, finally, director of communications for Labour, where he became a key and ultra-loyal right-hand man to Neil Kinnock in the latter’s heroic effort to ditch the party’s most voter-alienating policies.

Mandelson was a presentational master, of course, and during the Kinnock years, he also used those skills to promote Gordon Brown and Tony Blair – in that order – as the party modernisers who could ensure an election-winning future. And as a core architect of the New Labour project, Mandelson was a highly successful member of the trio that set the ground for what would come after John Smith’s untimely death in 1994.

What is striking, however, is how tired Mandelson became of being a backroom boy. Having toiled as communications director, then as a key lieutenant in Blair’s leadership campaign (in which he had to be codenamed “Bobby” to ensure that no potential supporters would be alienated by his presence), and then after 1997 as the ministerial eyes and ears for Blair, he yearned for a cabinet job and a department of his own. Which was why he was so happy to become the trade and industry secretary in 1998. The power – or some of it, anyway – was finally flowing his way.

Power, influence and infighting

One result of the Epstein files is the closure of the final chapter in one of the great psychodramas of British politics of the last 30 years: the relationship between Mandelson and Brown, which was in many ways deeper and more turbulent than that between Brown and Blair.

It was certainly not for merely personal reasons that, as Brown demanded for the second time a government inquiry into what Mandelson was leaking to Epstein, he described Mandelson’s actions as “inexcusable and unpatriotic”. A son of the manse, Brown may have his faults, but he has a vastly greater sense of the proprieties of government, it turns out, than the man who was his de facto deputy in the crucial years between 2008 and 2010.

At the time, Brown and the late Alistair Darling were engaged in the toughest of tasks that any prime minister and chancellor can perform: stabilising the economy after a financial crash, and allaying anger and unrest among the general public. The leaks of market-sensitive data to a super-rich networker connected to the global financial services industry endangered the first of these goals, and were an attempt to sabotage the second.

Nevertheless, Mandelson must have known, on some level, that the repeated real-time leaks and the contemptuous terms in which he shared his views on Brown with Epstein constituted an outstanding betrayal of his one-time hero and mentor, who had brought him back to the top tier of government. And this speaks to another aspect of the inner workings of Mandelson’s mind: he takes dangerous risks, which are always close to blowing up in his face. The first real evidence of this self-destructive streak, and also his dependence on a rich man, was the £373,000 loan he secured in 1996 from his fellow Labour MP Geoffrey Robinson to fund a house in fashionable Notting Hill.

After Labour entered government the following year, this home loan would underline the deep contrast between Mandelson’s role as Tony Blair’s radar – the “minister for looking ahead”, spotting and pre-empting political challenges – and his chronic inability to do the same for his own career. Until it was exposed by some of Brown’s lieutenants (of whom Robinson himself had been one), the loan remained, disastrously, a deep secret about which he did not tell his closest friends, or even Blair himself.

Installed in 1998 in the cabinet as trade and industry secretary, he was also guilty of a serious breach of protocol (though much less serious than that involved in his leaks to Epstein) by failing to mention it to the permanent secretary, even though Robinson was under investigation by his own department.

The rough parallel here is that, although Mandelson’s association with Epstein after the latter’s 2008 conviction for procuring and grooming a 14-year-old girl was already known about when he was appointed ambassador to the US, he lied about the depth of that association when he was asked about it. But there are also key differences between the two stories.

First, the entanglement with Robinson was largely victimless, as no friendship with Epstein could ever be. Here, of course, Mandelson was anything but alone. The queue of the rich and powerful – presidents, foreign prime ministers, CEOs of vast multinationals among them – who flocked to consort with Epstein after his first conviction for sex-trafficking a minor remains a breathtaking and horrifying fact of 21st-century life.

Secondly, his career after his 1998 resignation was very far from over, as it now so definitely is. He took the advice given to him after his resignation – by Brown, as it happens – to work his way back. Which he broadly did, and within a year he was installed as Northern Ireland secretary, a job at which he was arguably successful, as he had been at trade and industry. Until, of course, he made a phone call to the Home Office on behalf of one of the Hinduja brothers, who had contributed £1m to the Millennium Dome and was seeking a British passport. The misdeed was lesser than the Robinson loan, but once again it was exposed, and it became the second episode to bring him down.

But while there are parallels, none of this quite explains how Mandelson so willingly fell into the clutches of Epstein. True, as Blair’s business secretary, he’d had a seductive taste of the super-rich high life – taking, for example, free transatlantic flights on the private jet of the lingerie multimillionaire Linda Wachner, and staying in her Long Island home. But why Epstein?

Money, of course, played a huge part in it. Epstein paid £10,000 for his partner Reinaldo Da Silva’s osteopathy course in 2009; add this to an alleged payment of £75,000 in 2003-04, which Mandelson says he has no recollection of. By then, Mandelson was being paid £104,000, and was reportedly in line for a pay-off estimated at £1m from his job as an EU commissioner.

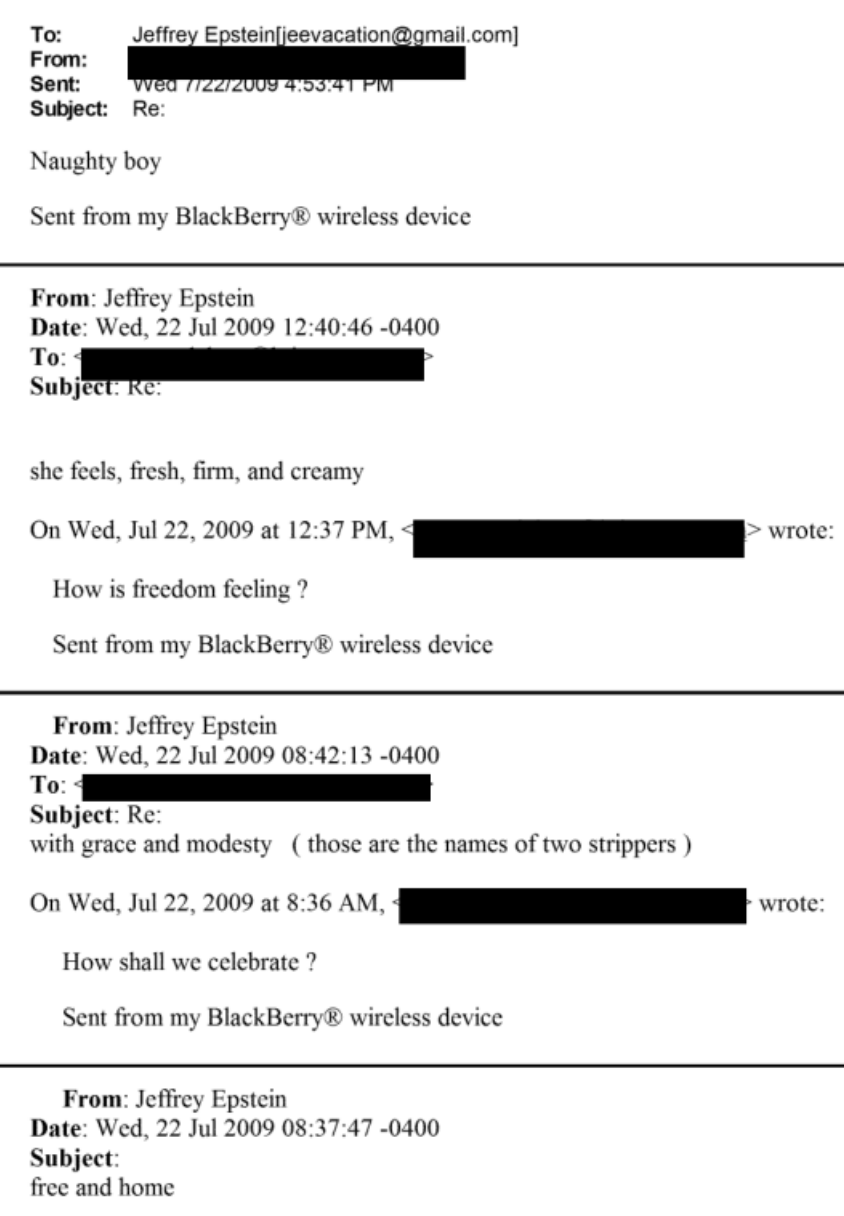

It is also clear that Epstein expected something in return, complaining querulously in one 2012 email: “I am disappointed by what appears to be a one-way street.” We can see Mandelson replying: “I have never left your side” – justly, given the stream of highly confidential information we now know he was supplying to Epstein.

The commentator David Aaronovitch, who knew Mandelson well in the earlier part of his career, has highlighted another aspect of his personality that might explain the relationship with Epstein: a lifelong desire to impress his bosses, or those with more power than himself. That does indeed seem to shine through the Mandelson emails, as in the potentially market-moving, as well as self-aggrandising, one he wrote to Epstein in May 2010, when he announced “I finally got him to go”, hours before Gordon Brown formally resigned the premiership. See too the lubricious, sexually charged banter between the two men that so excruciatingly surfaces on occasion.

But there is something even more pertinent than this. Which is that Mandelson was clearly after a job, specifically with JPMorgan. Discussing this prospect, Mandelson tells Epstein after Labour’s election defeat, “I am getting very anxious about how I am going to earn my living from August 13!”

Given that Mandelson’s high standing as a former cabinet minister meant he could have had the pick of decent public or private-sector jobs in the UK, it seems he was instead seeking his place in what Epstein called “moneyland” – the very big bucks indeed.

This, of course, speaks to the weakness at the heart of Mandelson. While he was comfortable with elites in a way in which Starmer could never be, this also brought its own problems. In 1998, Mandelson famously said: “I am relaxed about people getting filthy rich, as long as they pay their taxes” – a controversial and deliberate remark to signal that New Labour was pro-enterprise, not anti-success. Indeed, a keenness not to look too “old Labour” to the Trump administration may go a little way to explaining Starmer’s blind spot in so easily overlooking Mandelson’s problematic career history and giving him the top Washington job.

Mandelson seems to be drawn to wealth because it signals success in a world beyond politics, and a permanence beyond public office. We can see his mind working this way in the interview with Katy Balls in The Times, which took place after he had been sacked from his ambassador position by Starmer, but before the full horror of the Epstein revelations that showed the full depth of his treachery. This was a man who still thought he stood a chance. He told Balls that a friend had reminded him: “Remember, tough times don’t last. Tough people do” – indicating that he was holding on to the belief that, in the midst of adversity, he wasn’t done yet. Wealth and wealthy people may have provided him with a shield against the vulnerability of public life. In the moneylands of Epstein and his ilk, normal rules simply don’t apply.

There is one other psychological factor that might explain the way his mind works – at least in relation to his betrayal of Brown. The rupture between the two of them had lasted since Blair became leader in 1994, interrupted by only sporadic reconciliations. Indeed, several times, while still in Brussels, Mandelson cast not very subtle aspersions on Brown’s leadership. Did he fantasise that by bringing him back, Brown had shown that he needed him, and that he, Mandelson, had therefore at last “won” the long battle between them? Would he have shown the same brazen disloyalty if Blair had been prime minister?

Either way, it is hardly surprising that Brown is so furious, for commendably proper reasons of state, to discover that despite his persistent outward loyalty, Mandelson was, for the most dubious of motives, actually acting as Epstein’s mole in government. His actions at the time do seem to have been perilously close to espionage, and I doubt he will be the only one to pay a heavy price.

The two main consequences of this are not hard to spell out. One is the further blow to the already severely weakened faith the public have in politics – a feeling that “they’re all in it for themselves” (which they aren’t) that is becoming more difficult to shake off by the day. This is a gift to Reform – wholly undeserved, since it’s a safe bet that a Nigel Farage government would be worse in this, as in so many other respects. But this scandal will now be the stick Farage can use to beat the so-called “political establishment”.

The other is the damage to the Labour Party that Mandelson was born into. For this, he cannot be solely blamed; Starmer badly miscalculated by appointing him to Washington, when the basic fact that Mandelson had continued any relationship with Epstein after his conviction should have been enough to rule him out. Nevertheless, it remains true that the man who did so much in the Eighties and Nineties to help make his party electable has become the central figure in a saga that threatens to make it unelectable all over again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks