On the Front Porch, Black Life in Full View

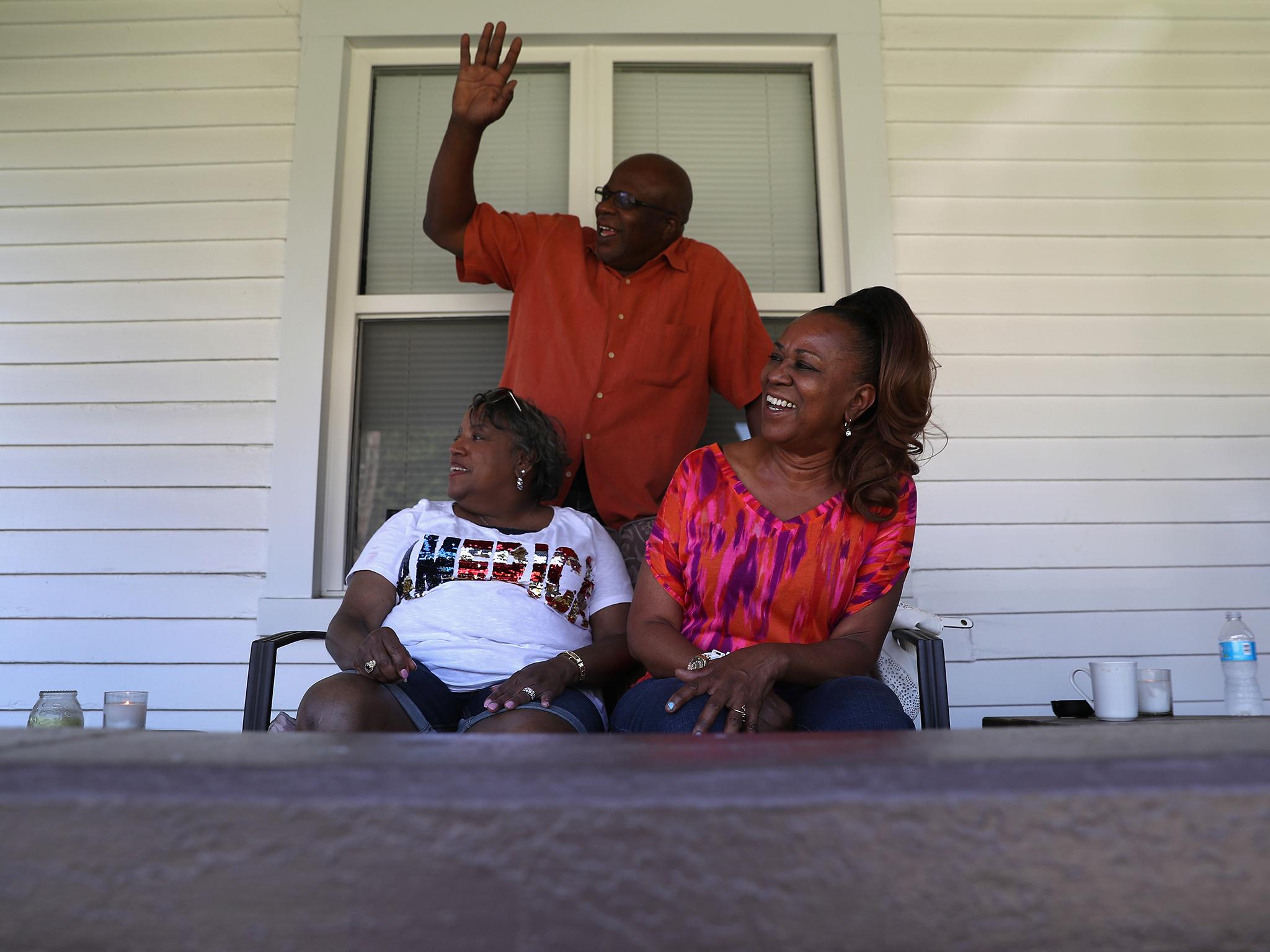

From the narrow shotgun homes of Atlanta to the dormer-windowed bungalows of Chicago, the front porch has served as a refuge for black Americans

It is a place to gather after Saturday night dinners and after the church doors open on Sunday afternoons. A dais upon which to sing lullabies and honour memories, to weave folklore and family stories, the kind carried from greats to grands, from one generation to the next.

In its framed simplicity, the front porch has been a fixture in American life, and among African-Americans it holds outsize cultural significance.

From the narrow shotgun homes of Atlanta to the dormer-windowed bungalows of Chicago, the front porch has served as a refuge from Jim Crow restrictions; a stage straddling the home and the street, a structural backdrop of meaningful life moments. It is like the quietest family member; a gift where community lives and strangers become neighbours.

Zora Neale Hurston, an exquisite chronicler of black Americana, understood the magic and necessity of the porch as a gathering place to witness and soak up history. Her prose cast the porch as a setting for storytelling.

The porch has also inspired scholarship. Germane Barnes, a black architecture professor at the University of Miami, has travelled the US studying its role within black vernacular. “Architecture and identity go hand in hand,” says Barnes, 33, who grew up in Chicago.

His research took him to Detroit, where he found a historical city undergoing an economic rebirth and black homeowners eager to share memories of watching life unfold on their front porches.

The porch is where a retired teacher witnessed a race riot. It’s where a nurse and her mother sat on a swing, morning after morning, until their relationship blossomed into a friendship. It’s where a community organiser chose to tell stories, full of richness and hope, to help preserve her worn but proud neighbourhood.

The Gathering: ‘I still remember the laughter and feeling safe’

When the wooden doors of Messiah Baptist Church opened after service on Sunday afternoons, members of the congregation, dressed in their Sunday finery, walked to a two-storey bungalow on Humboldt Street to gather on the Parnell family’s front porch. It was stately, with green columns, and framed by a black iron gate. Eleanor Parnell’s mother would pass out snacks to the children and cups of coffee to the adults.

“Our porch was the gathering place. People in our church would come to wait for their rides home,” says Parnell, 61, holding tight to those memories of her childhood during the 1960s. “I still remember the laughter and feeling safe.”

As a college student, Parnell moved into the home across the street, which was also owned by her parents. In the mornings, her mother, then in her 60s, would come by for a cup of coffee. They sat on a swing on the porch and bonded as adults. “The porch helped us transition into this wonderful friendship,” says Parnell, a registered nurse. “I like to think the coffee, the porch and the conversations made us girlfriends.”

The Prize: ‘I worked hard to get here’

“When I was a child, after church, the preacher would come by and sit with my mother on our porch. She would serve poundcake and coffee,” Margaret Riley recalls. “I still see the porch as an outdoor living room. I want it to be respectable because it is sacred.”

In 1989, Riley saw a bungalow on a corner lot with a front porch just waiting to be loved into something beautiful. The two-bedroom house was exactly what she had wanted – a gem that defied the expectation of what she could afford on her salary as a custodian, and that was big enough for her to raise her two boys in. She saved for a year for a down-payment to buy the house and eventually turned the tiny concrete stoop with two steps into a wooden porch with four.

To Riley, the porch was more than just an entrance into a home. It was a measure of success, a symbol that she had made it. She proudly decorated her porch with blooms, welcome signs and a lawn chair where she sits and waves to children and parents as they pass by. “I worked hard to get here,” she says. “The porch is where I connect, where I became a neighbour.”

The Heart: ‘The porch is where I think, where I conjure up the things that I want to create to uplift my community’

Shamayim Harris was still grieving the death of her 2-year-old son on the morning she sat on her front porch and envisioned a village rising from the surrounding emptiness. Sipping a cup of black tea and burning a bundle of sage, she saw more for her neighbourhood, withering under the weight of time and neglect.

That was the quiet beginnings of what is now Avalon Village, a green development project born on Harris’s porch and inspired by her youngest son, Jakobi Ra, who died in a hit-and-run accident 11 years ago. The growing village, composed of 32 abandoned parcels, now includes solar-powered streetlights, a park, an educational centre and a marketplace for women entrepreneurs.

“This was about healing and making my community safe and beautiful,” says Harris, 53, a minister, community organiser and former school administrator. From her porch, which is lined with seats and potted plants, Harris now hands out bags of free fruit and vegetables, holds community meetings and counsels couples. “I have always been a porch sitter. The porch is where I think, where I conjure up the things that I want to create to uplift my community,” Harris said. “And now, it’s the heart of this village.”

The Protector: ‘The porch plays this crucial role in my recovery’

Audra Carson was riding her friend’s purple bike as fast as her 7-year-old legs could pump the pedals. “Mom! Dad! Look, I’m riding the bike,” she proudly told her parents, who were sitting on the front porch, as they did virtually every Sunday after church.

The Carsons were the second black family to move into their neighbourhood in northwest Detroit. Most of the homeowners worked in the nearby car factories. As Audra careened down the pavement on the bike, the front tyre hit a rock and she was suddenly tumbling over the handlebars. Her face slammed into the pavement. Blood began to gush. She lay motionless in the street. Her father silently swooped from the porch, hurtling towards his baby girl.

“He gathered me. He and my mum wrapped my head in towels, put me in the car and rushed to the hospital,” says Carson, who is now 53 and founded a tyre recycling company. “If my parents had not ben on the porch, who knows how long I would have been lying there,” she said. “The porch played this crucial role in my recovery. I have come to think of it as my protector.”

The Stage: ‘You sit on the porch and tell stories. Porches are built for storytelling’

For Cornetta Lane, Core City was the childhood neighbourhood where she fell in love with weeping willows. Four years ago, she came across a description of her Detroit neighbourhood in a news article, but it was called something different to Core City. To Lane, a community organiser, the new name felt like erasure. “It was just so upsetting,” she says. “I knew then I needed to find a way to preserve the historical identity of my neighbourhood.”

For this rescue mission, Lane chose porches, people and powerful storytelling, the kind that could carry this tattered but resilient neighbourhood to a new vibrant chapter as the city rebuilds. Lane, 31, coordinated a bike tour through the community. It’s called Pedal to Porch. At each stop, the residents use their front porch as a stage to share intimate stories about their neighbourhood.

“I never considered doing this without the porch,” Lane says. “It is a natural place for convening. You sit on the porch and tell stories. Porches are built for storytelling.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks