The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

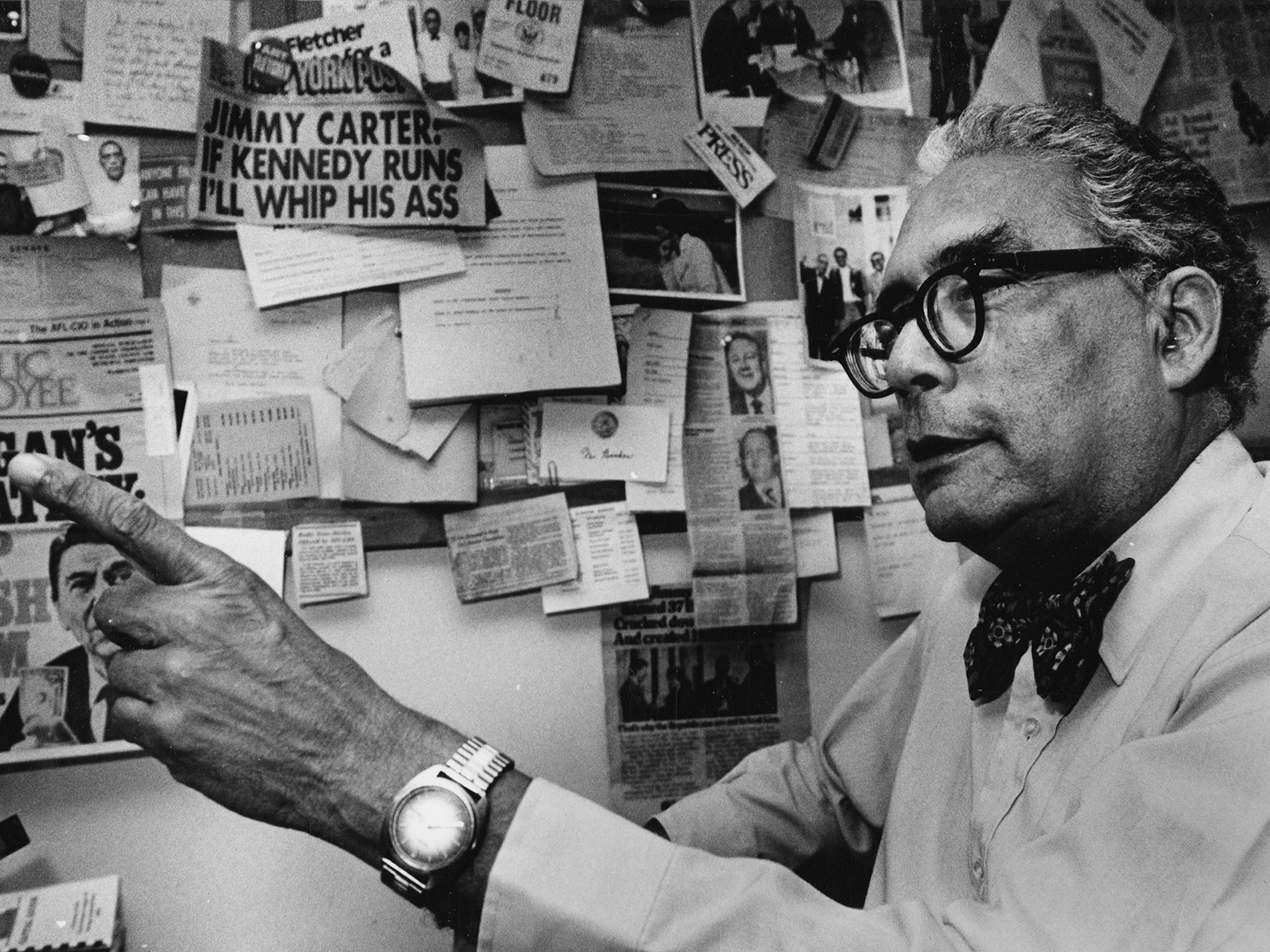

Simeon Booker: Chronicler of America’s civil rights struggle who made his name covering the 1955 lynching of a boy

He weathered flak when he joined The Washington Post as its first black reporter – both in and out of the newsroom – before breaking off to empower the African-American press

The photographs stunned the America: a 14-year-old boy dead in a coffin, his head crushed, an eye gouged, his body disfigured beyond recognition from an agony in which he was beaten, shot, tied with barbed wire to a weight and submerged in the Tallahatchie River of Mississippi.

The young man was Emmett Till. His murder in 1955 – punishment for the transgression of whistling at or otherwise offending a white woman – became the most infamous of the thousands of lynchings inflicted on African-American people in the segregated South.

Till’s death galvanised the civil rights movement, but only after Simeon Booker helped deliver the story to a national audience.

Few reporters risked more to chronicle the civil rights movement than Booker. He was the first full-time black reporter for The Washington Post, serving on the newspaper’s staff for two years before joining Johnson Publishing to write for Jet, a weekly, and Ebony, a monthly modelled on Life magazine, in 1954 – he was their Washington bureau chief for five decades.

From home bases in Chicago and later in Washington, Booker ventured into the South and sent back dispatches that reached readers all over America. He was in Chicago, Till’s hometown, when he heard that the young man had disappeared while visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi.

Booker instinctively went to the home of the young man’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, and earned her trust while she was in a state of grief. He was with her at the funeral home where, over the objections of everyone present, she insisted that the casket bearing her son’s mutilated corpse be opened. Booker described the scene in Jet: “Her face wet with tears, she leaned over the body, just removed from a rubber bag in a Chicago funeral home, and cried out, ‘Darling, you have not died in vain. Your life has been sacrificed for something’.”

Jet photographer, David Jackson, took images of Till’s body, which thousands of mourners observed at his funeral.

No mainstream news outlets published the images of Till’s body, according to an account decades later in The New York Times. But their appearance in Jet and several other African-American publications helped make the Till murder “the first great media event of the civil rights movement,” historian David Halberstam wrote in his 1993 book The Fifties.

Like Till, Booker grew up in the US’s North and said he had never entered the Deep South before travelling to Mississippi to cover the trial of Till’s accused killers, Roy Bryant and JW Milam. An all-white jury acquitted the defendants after deliberations lasting roughly an hour. Later, Bryant and Milam confessed to the killing.

Booker was in constant peril as a black journalist reporting in the South. But the Till case presented particular dangers.

“The first day we got there we went over to Till’s grand-uncle’s house and men in a car with guns forced us to stop” Booker told the Times. After the verdict, he recalled, “the first thing we had to think about was getting to Memphis and getting out of there, because we were marked men. And they put us all on one plane, the reporters and witnesses and everybody.”

Booker later became bureau chief in Washington and established the Johnson company’s office in the capital. After a lengthy search for accommodations in the then-segregated city, Booker and his colleagues found two rooms in the Standard Oil building on the city’s Constitution Avenue.

As one of the few black reporters in Washington, he wrote a column for Jet called “Ticker Tape USA” and led editorial coverage of US politics at a time when black reporters were as excluded from news events as they were from everyday life. He covered 10 presidents and travelled to Southeast Asia to report on the Vietnam War.

And then he returned to the South, documenting the civil rights struggle. For his safety, he sometimes posed as a minister, carrying a Bible under his arm. Other times, he discarded his usual suit and bow tie and for overalls to look the part of a sharecropper.

Once, in an incident retold when Booker was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists’ Hall of Fame in 2013, he escaped a mob by riding in the back of a hearse.

He wrote that he was “never prouder of Jet’s role in any story” than in 1961, when he helped cover a Freedom Ride from Washington to New Orleans, an interracial effort to test compliance with a ban on segregated interstate transit.

A mob firebombed one of the buses in Anniston, Alabama. Thugs forced their way aboard Booker’s coach and beat the protesters. In Birmingham, Alabama, Ku Klux Klansmen waited to beat them again.

With help from the office of US Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Booker and the Freedom Riders were eventually flown to safety. But such demonstrations continued, and integration was enforced in interstate travel.

Booker was in Baltimore where his father, a Baptist minister, was the director of a YMCA for black people. The family later moved to Youngstown, Ohio, where his father opened another YMCA.

“From an early age, I knew I wanted to be a writer,” Booker told a Youngstown newspaper. “Teaching and preaching were the best advances for blacks at the time. But I wanted to write.”

He received an English degree in 1942 from Virginia Union University, a historically black institution in Richmond, then began his career at the Baltimore Afro-American. He later joined the Cleveland Call and Post, also an African-American publication, where he received a Newspaper Guild award for a series covering slum housing – and where he was fired for trying to unionise the staff.

In 1950, after several previous applications, he received a prestigious Nieman Foundation fellowship for journalism at Harvard University.

With that under his belt, Booker wrote to numerous newspapers seeking employment. “The only one to answer me,” he told The Washington Post years later, was the newspaper’s former publisher Phil Graham.

Graham had told Booker, “If you can take it, I’m willing to gamble.” By that he meant the unrelenting difficulty Booker would encounter in the segregated capital. Indeed, when the new recruit introduced himself as “Simeon Booker from The Washington Post,” people laughed.

“If I went out to [the scene of a hold-up], they thought I was one of the damn hold-up men,” Booker told The Post. “I couldn’t get any cooperation.”

Booker said he eventually determined that The Post wasn’t “prepared” to have a black reporter on its staff.

“It was all new to them, having a black guy in the newsroom,” he recalled. “It was recommended to me that I only use the bathroom on the fourth floor – editorial – so I did. I could eat in the cafeteria, and I was thankful for that. But I was always alone.”

After a two-year tenure that he described as a “social experiment,” he joined publishing company Johnson. Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff describe in their Pulitzer prize-winning book The Race Beat (2006) that in Booker’s time, African-American newspapers were suffering crippling circulation losses. The Johnson magazines offered the alluring opportunity to reach vast national audiences, and Booker remained with the company until his retirement, around his 90th birthday.

In his reporting, Booker developed a working relationship with Cartha “Deke” DeLoach, a top aide to J Edgar Hoover at the FBI, and credited the bureau with helping keep him safe when he travelled to the South. He described the FBI as “a kind of co-engineer with us,” adding that “Jet and Ebony never would have been what we were without the FBI.”

His account appeared in conflict with later discoveries by historians that the FBI had sought to undercut Martin Luther King Jr and the movement he led. David J Garrow, a Pulitzer-winning historian, told The Post that Booker’s flattering accounts of the FBI were “one of the most hilarious snow jobs in American history.”

Booker described the relationship as simply a matter of staying alive.

“Maybe [they] looked at me as some kind of informer. I was giving them information – far as where I was going, who I was going to cover – and they were giving me information about staying safe,” he told The Post. “I’d have never gotten into the South were it not for J Edgar Hoover and Deke DeLoach. DeLoach saved my neck more times than I can remember.”

More than three decades earlier, he had received the National Press Club’s Fourth Estate Award. At the awards ceremony, he recalled that he had “one compelling ambition.”

“I wanted to fight segregation on the front lines,” he said. “I wanted to dedicate my writing skills to the cause. Segregation was beating down my people. I volunteered for every assignment and suggested more. I stayed on the road, covering civil rights day and night. The names, the places and the events became history.”

Simeon Saunders Booker Jr, born 27 August 1918, died 10 December 2017

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks