Chinese New Year 2018: What does the Year of the Dog actually mean?

Come 16 February, the Chinese calendar rolls into a new year. David Barnett – a proud rooster – delves into the rich history and mythology of the zodiac

At my local Chinese takeaway, January was greeted with the traditional handing over of the calendar along with my order, a brightly coloured affair that’s been a household fixture for some years.

Ah, I said, unfurling the scroll. It’s the Year of the Dog! That’s my birth year!

This was not greeted by the jubilation and letting off of fireworks (or perhaps a free bag of prawn crackers) that I was half hoping for, but rather a tight smile.

It was only later I found out why. Rather than being a good omen, as I’d assumed, the dominant Chinese zodiac year for those whose birthdates match up to the animal in the 12-year cycle is actually very unlucky indeed.

However, there is a happy end to this story – Chinese New Year begins on 16 February, and my birthday is in January, so I’m actually a rooster. For the rest of you, though, who were born between next Friday and 4 February 2019 in the years 1934, 1958, 1970, 1982, 1994, 2016 or 2010… well, all I’ll say is try to avoid the colour red in the coming year, and steer clear of the numbers one, three and nine. So if you live in London and catch the 139 bus from Golders Green to Waterloo on a regular basis, it might be prudent to invest in a pair of walking boots.

If you are a dog, you’re not alone. Perhaps the most high-profile dog is none other than the US President, Donald Trump. Indeed, if you happen to find yourself in Taiyuan, the capital of China’s Shanxi province, you won’t be able to miss a gigantic dog statue outside a shopping mall which bears more than a striking resemblance to Potus, flyaway golden hair and all.

Of course, you won’t be wishing ill on Donald Trump in the Year of the Dog, and to be fair, it doesn’t necessarily mean bad luck. Take Elvis Presley, who weren’t nuthin’ but a hound dog despite being born in 1935 (he just squeaked in because, like me, his birthday was in January). After his big comeback in 1969, dog year 1970 was a big one for him as his re-booted reputation grew immensely. Bill Clinton was, as is Trump, a year into what would turn out to be his first term of office in the White House in 1994, so he was probably not having too bad a year.

Other famous dogs include Dame Judi Dench, Sophia Loren, Alan Rickman, David Bowie, Steven Spielberg, both Prince William and Kate Middleton, Justin Bieber, Madonna and Mother Teresa.

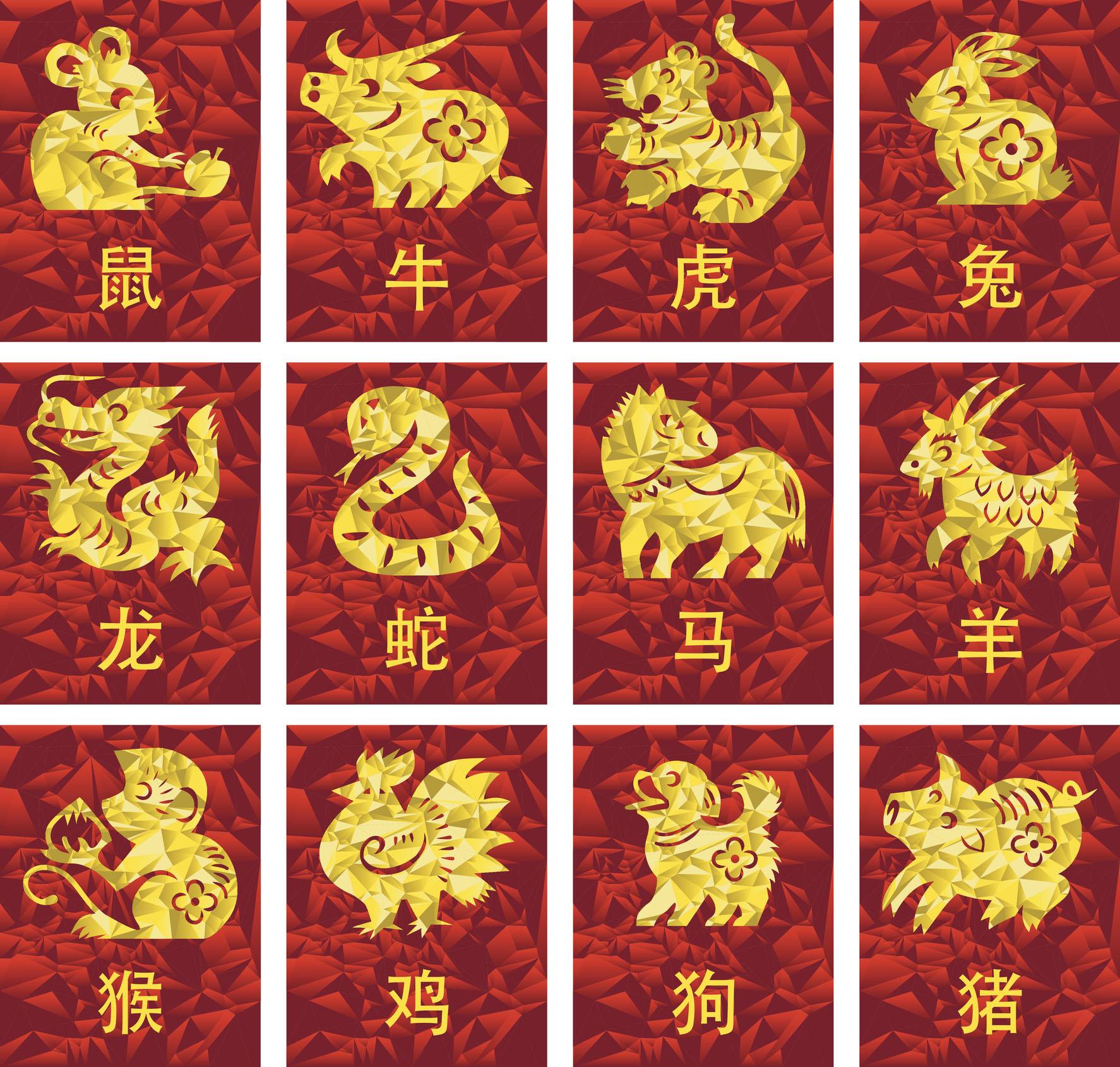

There are 12 animals represented on the Chinese zodiac; as well as the dog there is the boar, or pig; the rat; the ox; the tiger; the rabbit; dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey and the rooster, my own sign which won’t see the light of day again until 2029, having been front and centre last year.

You might be thinking that notable by its absence is the cat, which is usually well represented in Chinese culture, especially in those “beckoning cat” trinkets. Well, there is of course a story to that, for which we must go back to the far ancient times when the Jade Emperor decreed that the earthly calendar would be represented by 12 animals, and ordered the beasts and birds of the world to rock up to his palace, the first dozen getting the job.

So the story goes, the cat and the rat were huge pals back in those days, and decided to journey together to the Jade Emperor’s palace to take up their places on the zodiac. But apparently the rat forgot to wake up his friend (yeah, right, if you believe that…) and set off on his own. When the kitty finally dragged itself out of bed, friend rat was well on his way. Not only that, but he’d made some new pals, notably the ox, who agreed to carry the rat on his back on the long journey. Once they got to the Jade Emperor’s palace, the rat was all like, yeah, cheers for the ride, hopped off and was the first one through the gates.

The animosity between oxen and rats isn’t well recorded, but if you ever wondered why cats hate rats, then there’s your answer.

These days, the Chinese New Year is a massive, two-week celebration, and not just in mainland China; there’ll be a huge event on the New Year weekend in London’s Chinatown, and other Chinese communities around the world.

In fact, “Chinese New Year” is a bit of a misnomer because the event is also marked in Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam and beyond… in fact, a sixth of the world’s population will be having their New Year’s Day next Friday, rather than on 1 January.

But why different new years anyway? The Gregorian calendar, on which most of the west marks time, is a solar calendar, based on the time it takes for the earth to travel around the sun, which is of course 365 days give or take a few straggling hours which are lumped together into an extra leap year day every four years, split into 12 months.

The Chinese and other predominantly eastern calendars are based on a lunar cycle, which does tend to make more sense in terms of cultures with a venerable history. The sun pretty much looks the same whenever you look at it; the moon waxes and wanes and its progress throughout a month can be observed and recorded without the need for any special astronomical instruments.

More than that, though, the Chinese calendar especially was based on an agricultural pattern. The formation of the calendar based on the movements of the moon is said to date back to the Xia dynasty, about 16-21 centuries BC.

But whereas the Gregorian calendar has New Year’s Day firmly on 1 January every year, the Chinese New Year is more of a moveable feast. This is because back when the Chinese calendar was being formulated it was based on the lunar cycle of roughly 29.5 days, which when multiplied by 12 gives you 354 days – 11 short of what we use as standard today. This means that the date of the New Year hops around the first half of February quite a lot.

A little over a century ago, when the Republic of China was founded in 1912, the western Gregorian calendar was adopted, but the Chinese New Year festivities persist, often called “Spring Festival” as, in keeping with its agrarian beginnings, this was the start of the new agricultural cycle of ploughing, sowing, nurturing and harvesting crops.

There are many traditions associated with Chinese New Year which last today. Fireworks, of course, and the impressive dragon puppet parades. There’s also the tradition of younger family members receiving gifts of cash in red envelopes, a practice known as hongbao. These days, though, it’s a bit more hi-tech, with several Chinese companies developing phone-based apps via which cash, or sometimes virtual currency, can be deposited by tech-savvy older folks into their kids’ accounts.

One of the most popular, the WeChat red envelope app, was launched in 2014 and by New Year 2016 the developing company Tencent was reporting a whopping 2.3 billion individual transactions.

Cultures other than China have their own traditions around the Spring New Year. In Korea, celebrants dress up in colourful costumes and practice a ritual offering of tea. On Bali, in contrast with the brash, loud celebrations of other territories, New Year – which falls a little later in March – is seen as a day of rest and quiet contemplation. Even later, in April, the lunar calendar adopted by the Indian states of Karnataka, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh sees celebrations marked by fireworks, new clothes, and a snack of mango-based sweet and sour chutney.

The Chinese New Year will run until 4 February 2019, and the dog will make way for the Year of the Boar. Fingers crossed we get there; I’m not sure if Donald Trump has seen that huge statue of him in China with a decidedly canine makeover, but it feels worrying like exactly the sort of stupid thing he’s likely to start a devastating nuclear war over. Which would be bad luck for everybody.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks