Why joining the local library is the best thing you can do in 2026

Library use is dwindling, with less than a third of the UK population using the service in the last year. But with community (and the latest hardbacks) on offer, Lydia Spencer-Elliott argues that membership is a must

It took me four years of living 12 minutes away from Battersea Library to eventually register as a member. Despite its octagonal turret and red brick exterior, the 19th-century building was, embarrassingly, no match for the apps sucking my attention towards my phone – until the start of 2025, when the number of books stacked in piles across my tiny flat began to feel wasteful in terms of both paper and cost. I was spending £15 a pop on new hardback releases, only to let them gather dust within a matter of months of reading them, with some borrowed once or twice by passing friends. So, with trepidation, I meandered through the open arches to the shelves.

When the first public lending library opened in Manchester in 1852, it was so busy during its first week that a police officer was assigned to conduct crowd control around the overflowing borrowing desk. “This meeting cherishes the earnest hope that the books thus made available will prove a source of pleasure and improvement in the cottages, the garrets, and the cellars of the poorest of our people,” said Oliver Twist author Charles Dickens at the opening ceremony.

Cut to 2025 and, although 78 per cent of the population are now within a 30-minute walk of a public library, according to the Office for National Statistics, under a third of us used a library service in the last year on record – and of those, 27 per cent were bringing children to borrow books, rather than checking out novels or non-fiction for themselves. More than 180 council-run libraries in the UK have either closed or been handed over to volunteer groups since 2016. Additionally, a third of those remaining have reduced their hours in a bid to survive cutbacks. Simply put, they’re on the ropes.

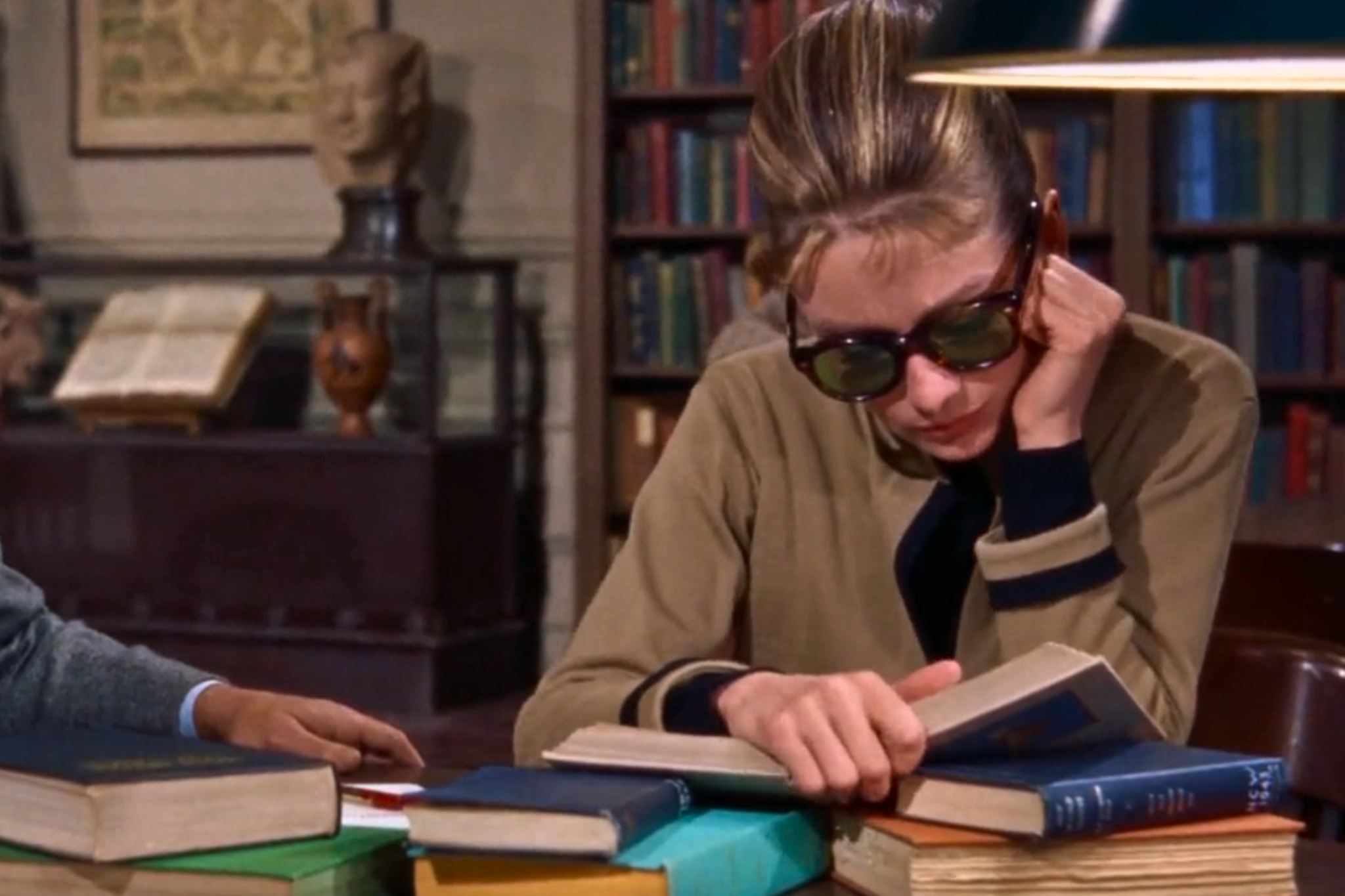

Characterised by quiet murmurs and the occasional rustling of pages, libraries are markedly more serene now than at the 1852 inaugural opening in Manchester. What will hit you square in the face, though, particularly in a city like London, is the immediate evidence of community: storytime for babies and toddlers, “crafternoon” art classes for all, tech mentoring for the elderly, coffee mornings, colouring clubs, knit-and-natter socials. It’s an institution entirely enveloped in kindness.

On one particularly hormonal afternoon, it’s enough to make me want to cry. Because the people who work here really, truly want to help you – whether that’s to pick a book, learn to sew, improve your English, convert a Word document into a PDF, or borrow a newspaper. I have, solemnly, never encountered an iota of disinterest or hostility from a member of library staff, which may not sound like much of a thing to marvel at, but means an awful lot when you’re standing alone on an emotionally cloudy day and in need of some kindness.

Aside from the people, the point is, of course, the books. I start slowly, perusing the shelves for readable titles just to get that part of my brain going again. Paperbacks I plump for initially include Kiley Reid’s 2019 debut Such a Fun Age, which follows a young Black woman called Emira who’s accused of kidnapping the child she babysits, and So Late in the Day by Claire Keegan, a 64-page-long 2023 Booker Prize finalist about a discontented man on his bus journey home.

But soon, the world is opened up further by the power of requests. As Battersea is part of Better Libraries, which operates in over 76 locations across London and the Midlands, it has access to thousands of books – not just the ones on the shelves. You order them, they’re shipped over and – for the price of just one British pound – they’re yours for a few weeks.

Soon, I’m reading releases as recent as Edge Hill Prize winner Saba Sams’ debut novel Gunk, published this spring. Then, Lily King’s coming-of-age Writers & Lovers prequel Heart the Lover, which was just released in October. I’m still reading hotly anticipated hardbacks, except now, more people get to share them.

One day, the fourth wall between me and these nameless co-readers is broken when a woman named Sue emails me to say she has found a slip that says I need to collect a handbag that I’d sent away to be repaired, wedged between the pages of a copy of The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden. I’d been using it as a bookmark. “As it has a recent date, I was wondering if you need this to pick up your bag, or shall I just bin it?” she asks, with her warmest regards. There’s that kindness again.

In the past year, the number of books I have read compared with the previous 12 months has tripled from 10 to 30. The most recent among these are It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me by Philippa Snow (a brilliant analysis of what it means to be a female celebrity), It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over by Anne de Marcken (a Fitzcarraldo zombie novel that’s in equal parts hilarious and devastating), and Happiness and Love by Zoe Dubno (a cynical yet soulful dinner-party satire).

This is not uncommon. One study found that, on average, library card holders reported reading 20 books over the course of a year. Non-card holder readers, to compare, logged 13 titles under their belts over the same period. In contrast, as has been widely discussed since the figures were released this March, YouGov found that 40 per cent of Britons had not read a single book in the past 12 months, with most getting through three per year. Among them, women (66 per cent), over-65s (65 per cent), and Labour voters (70 per cent) were most likely to be page-turners.

Reading is good for you. Various studies have found that picking up a book can help you live longer, reduce depression, improve your relationships, increase empathy levels, stave off dementia, improve sleep and minimise stress levels. In fact, research by the University of Sussex found that just six minutes of reading per day reduced stress levels by 68 per cent, based on measurements of heart rate and muscle tension. This was proven to be a more effective relaxation method than listening to music, walking, or having a cup of tea.

But few people do anything wholly because it’s good for them. Instead, we read for the magic. “You will only get pleasure from a book if you allow yourself to get lost in it,” explained beloved children’s author Michael Morpurgo to The Telegraph in October. “Books give you the time to discover yourself and the world around you. Take the reading habit away and we’re in trouble. Because what are we replacing it with?”

When Broad Green Library in Croydon became one of the many book-borrowing sites to close down this year, former members told the BBC they were “devastated” to have lost the sanctuary that provided them a third space to exist in away from their work, office or home. “It opened up a whole new life for me,” said one woman, Kiran Choda, a full-time carer for her elderly mother. “I’ve made friends through the library that I never would have had, and I just had a little time for myself, a little peace and serenity,” she added.

The success of Manchester Free Library 173 years ago followed decades’ worth of campaigning by politicians, writers and philanthropists to provide working-class people with access to books. This culminated in the passing of the Public Libraries Act in 1850, which allowed towns of 10,000 people or more to raise taxes to set up libraries. Industrial cities including Liverpool, Sheffield, Leeds and Birmingham were among the first places to follow in Manchester’s footsteps. By 1900, there were 300 locations to borrow books from.

The closure of Broad Green Library (according to Croydon’s executive mayor Jason Perry) came down to usage. Less than 10 per cent of residents were borrowing books. Although this data didn’t account for the visitors using the library as a study space, to access wifi, attend events, listen to talks or get involved in groups, that didn’t matter. Reading, when it comes down to it, is seemingly the only thing that can save a library from shutting its doors. Becoming a member is good for everyone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks