The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Is this the end of the celebrity chef era – or just a new course?

From Keith Floyd’s chaos to Jamie Oliver’s charm, the rise of the celebrity chef reshaped British food culture. But with TV turning away from food programming and TikTok cooks on the rise, Andrew Turvil asks if some of our favourite household names are nearing their sell-by date

So, who was your first celebrity chef crush? Who did you gaze at with slack jaw and wide eyes as they performed on television or social media? Who made you swoon and shout at the screen: “I want to eat that right now!” Who made you hungry for more?

Mine was Keith Floyd in the 1980s. Food programming had never seemed quite so cool and messy. He made cooking and eating seem like an act of visceral, hedonistic, unadulterated pleasure, and the chaos of it all was joyful to behold (chaos relative to what had gone before, anyway).

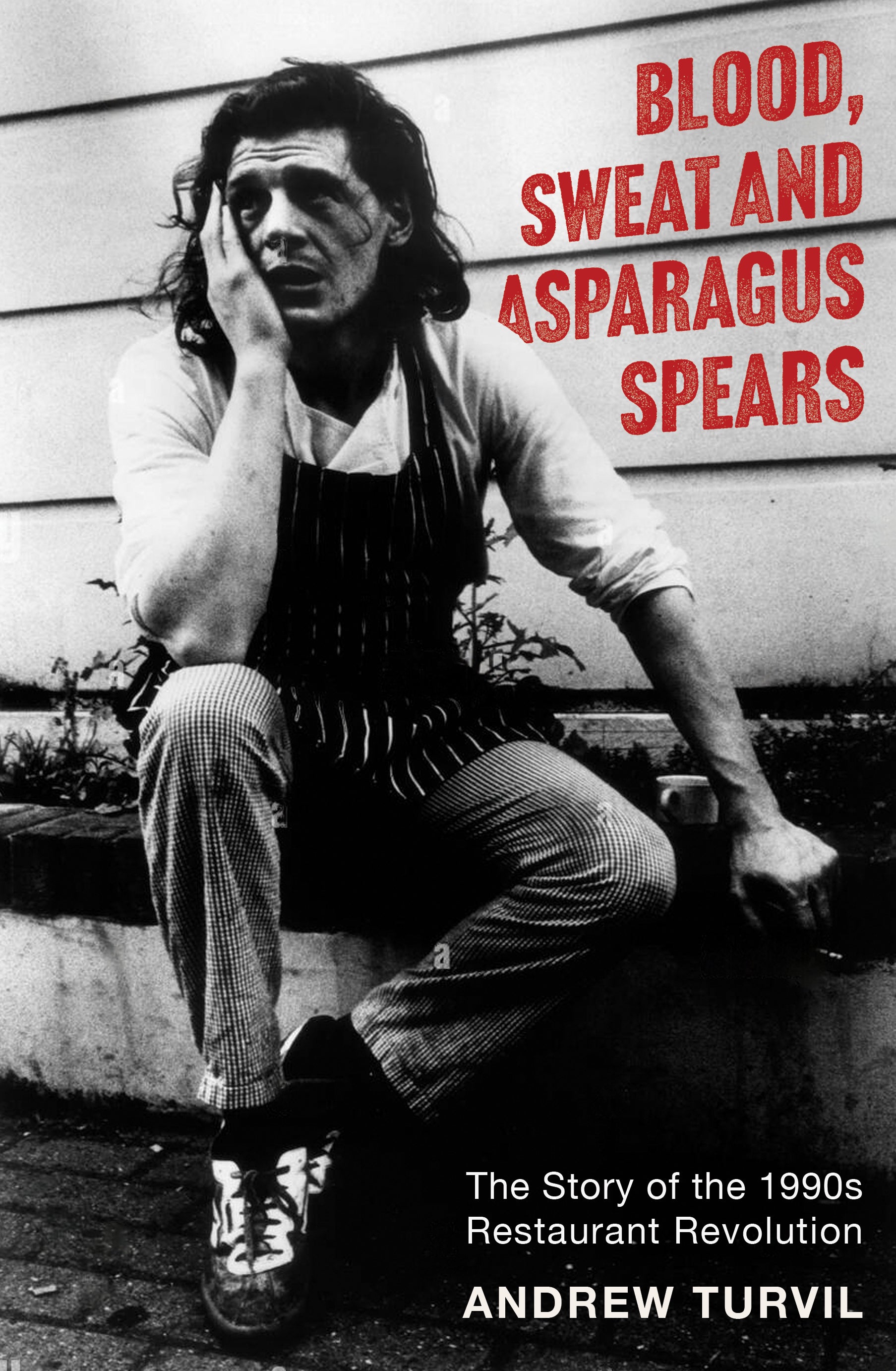

And then, when Marco Pierre White published White Heat in 1990, well, things would never be quite the same again. In my new book, Blood, Sweat and Asparagus Spears, I explore how the 1990s saw chefs emerge through the swing doors out of the kitchen and into the maelstrom of mainstream media attention for pretty much the very first time.

Sure, we’d had Fanny Cradock on our TV screens, Philip Harben, a posh American chap called Robert Carrier and the Galloping Gourmet Graham Kerr, but the 1990s saw a full-flavoured boom in new TV programming and cookbooks started flying off the shelves like loaves from a baker’s oven.

The 1990s were the start of the decade of the “celebrity chef”, which gathered pace into the new century. The chefs themselves were the stars for the first time. But with the fast-changing media landscape we have today, is the love affair over?

Public relations guru Alan Crompton-Batt is usually credited as the godfather of celebrity chefs in this country, but it wasn’t a mantle he wanted to carry, or actually deserved. He had certainly helped shine a light on chefs such as Nico Ladenis and White, but Crompton-Batt’s focus was never on getting his clients gigs on light entertainment TV shows. The Likes of Nico and Marco fostered an edginess, a soupçon of danger, and you’d better not ask for salt or your steak to be well done!

Marco was focused on gaining three Michelin stars, which he achieved in 1995 – the first Brit to do so – and it wasn’t until much later that you’d find him hawking chicken stock. Early celebrity chefs found fame on TV shows such as Ready Steady Cook and were part of a growing national fascination with matters of food. As their stock rose, a cookbook and TV show usually followed, and their restaurants (if they had one) got more bums on seats.

With Waitrose Food Illustrated first publishing in 1998, and Delia Smith ruling the roost at Sainsbury’s Magazine for a good proportion of the decade, food and cooking was on its way to becoming a national obsession. When Jamie Oliver hit the screens in 1999 with The Naked Chef, the democratisation of food was pretty much complete.

But according to stats from Ampere Analysis, commissions for food programming in the UK are down 40 per cent on last year. What’s happening? Aren’t we hungry any more?

Indeed, we are, for this is all about consumption. How we consume our media is different. Television, if not exactly yesterday’s chip paper, is no longer the first port of call for today’s foodies. Anyone wanting to “tell their food story”, be they a chef or a keen marketeer with a clever idea and zippy turn of phrase, needs to be digital. If Jamie Oliver were 20 and not 50, he wouldn’t be pitching his idea to a TV exec, he’d be doing it himself on TikTok, YouTube and Instagram.

And you know what? He is doing it. Jamie Oliver has 10.6 million followers on Instagram. Gordon Ramsay has 19.4 million. Perhaps the drop in food programming says more about the state of the TV industry than it does about celebrity chefs. It reflects the fact that young people are consuming their media differently, and the savviest chefs know that.

And just maybe, there’s been a saturation of food programming; I imagine they could roll repeats of our favourite cookery TV for decades to come and you still might not see the same programme twice. Food podcasts now feed us the chefs’ stories in their own words – the likes of The Go To Food Podcast, The Spectator’s Table Talk and Dish with Angela Hartnett and Nick Grimshaw.

The digital landscape can satisfy our hunger in moments, and food looks beautiful through a good camera lens – just perfect for the bite-sized format of your phone. Whether you follow a young creator such as Em the Nutritionist or are sticking with Jamie, you can find a recipe in minutes, even while you prowl the supermarket shelves. But even these new creators have dipped their toes into the old world, too, with Em’s book, Live to Eat: The Food you Crave, the Nutrition you Need, riding high in the Amazon charts.

But what’s No 1 in books on Amazon as I write, even beating Richard Osman’s latest murder mystery? Why, it’s only Jamie Oliver’s Eat Yourself Healthy. If we’re looking for a theme, there it is right in front of us. It’s no surprise, then, that Heston Blumenthal has just revealed a new Mindful Experience menu at the Fat Duck, aimed at those who want the same bang but with a health-driven twist.

Being a celebrity chef has never been a guarantee of success in the restaurant game. It’s a help, certainly, but even Jamie Oliver has been stung by the closure of his Jamie’s Italian brand of restaurants, Tom Kitchin shut Kora in Edinburgh this year and Simon Rimmer said a sad farewell to Greens in Didsbury. Each closure is a story of economic challenges and although that’s nothing new, perhaps it has never been so difficult to run a restaurant.

The podcasters and the influencers don’t have nightmares about liquidity or recruitment, but our food culture needs a strong restaurant sector to keep developing. The changes we’ve enjoyed over the last 30 years have come from the imagination and graft of professional chefs. Being a celebrity chef may no longer be the golden ticket it once was, but if you’re getting worried about your favourite chef, remember they are a resilient and pragmatic bunch. They exist in a world of economic fragility that most of us could only imagine. They wake up screaming about their GP (gross profit) and have to carry on through every economic twist and turn that comes their way. They are adapting to the new world order.

As a nation, we have a tendency to criticise people for being “too commercial” or “selling out”. It’s easy to do so from the comfort of your sofa, but activities outside of actually cooking in a restaurant kitchen have helped prop up many a good restaurant over the years. Jamie Oliver was criticised for working with Sainsbury’s in the noughties despite the fact that Delia Smith had ruled the roost at Sainsbury’s Magazine for a good chunk of the 1990s, but these days we seem more willing to accept the fact that a top chef like Tom Kerridge is the face of M&S. We’ve got used to it.

Those of us who wear our foodie badge with pride may well raise an eyebrow when Gordon Ramsay promotes the new wagyu burger at Burger King (“not made by Gordon”, declares the clever marketing campaign), but do you think it’s going to damage brand Ramsay? Not a chance.

The route to fame and fortune may have changed, but don’t expect celebrity chefs to be packing away their knives any time soon.

Andrew Turvil is the author of ‘Blood, Sweat and Asparagus Spears: The Story of the 1990s Restaurant Revolution’ (Elliott & Thompson), former editor of ‘The Good Food Guide’ and a restaurant critic

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks