The seamstress who conserves brutality

Julia Brennan restores the clothing of historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln but now she has turned to conserving textiles from atrocities some would rather forget, writes Zoey Poll

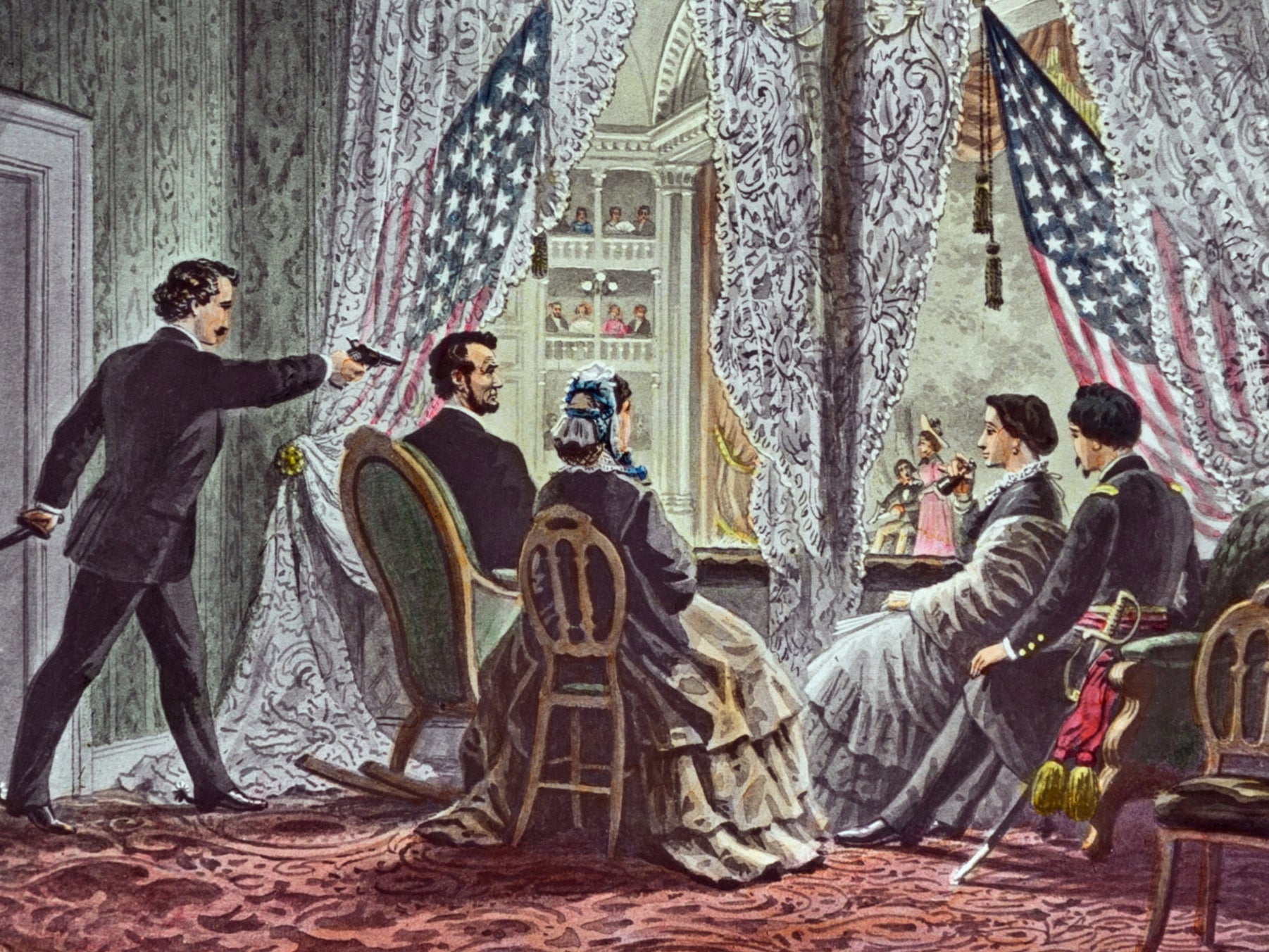

History regularly arrives on Julia Brennan’s doorstep: the greatcoat Abraham Lincoln wore on the night of his assassination or a rhinestone-studded “Sex Machine” jumpsuit that belonged to soulman James Brown.

Ms Brennan, a textile conservator, is a trusted resource for museums and collectors who call upon her to soften the damage done by time, the elements and mishandling. In her meticulous hands, centuries-old emotional states and habits — underarm stains on a wedding dress, cigar burns on a kimono that belonged to Babe Ruth — are analysed with care.

Over the past five years, she has also taught herself to conserve another kind of fabric: the clothes left behind by mass atrocities. She has salvaged thousands of garments from a notorious Khmer Rouge prison in Cambodia and a shipping container of bloodstained clothing collected from victims of the Rwandan genocide.

She says textiles are often forgotten but even a simple T-shirt can lend human specificity to an unthinkable act of violence.

“It’s that woman who wore that camisole,” she said. “It’s that man who had his hands tied behind his back, wearing his favourite brown canvas jacket.”

The garments are not only vivid reminders but also forensic evidence.

She says: “We don’t know what governments, conservators, stakeholders and historians will want to do in the future… what information they’ll mine from these collections.”

There were few precedents and no standard protocols for this work, which was funded in part by the US government. Some clothes had been housed in buildings that were not entirely sealed off from the weather and also let in “rodents, birds, micro-organisms… which, literally, eat them up”.

At the former prison in Cambodia – now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh – the director, Chhay Visoth, found the clothing in a disused storeroom in 2014, 35 years after the Khmer Rouge fled the city. The military uniforms and civilian clothes had been stuffed into refuse bags and were severely damaged by moisture and insects.

Mr Chhay recalled: “I explained to my staff, this is the great treasure of the museum collection; it’s not rubbish.” Impressed by Ms Brennan’s work for a museum in Thailand, he called on her for help.

She found an even more daunting challenge in the clothes worn by thousands of Rwandans when they were massacred in 1994 in the church where they had taken refuge. Survivors commemorated the victims by piling their clothes on the pews and in 1997 the bullet-riddled building became the Nyamata Genocide Memorial.

Two decades later, the remaining shirts, pants and skirts were rigid and unrecognisable – caked in red dirt and bat droppings. “It looked like a building fell on top of them,” Brennan says.

Conservation was difficult for many reasons but mainly because washing the clothes was out of the question.

Ms Brennan explained the responsibility of safeguarding this history as an outsider: “If we were to clean everything, we would remove a lot of witness-bearing information.” DNA might remain in the stains and at the Nyamata memorial the grime contained bone fragments.

She interviewed archaeologists, forensic scientists and others for advice and tested out techniques on charity-shop cast-offs she had soaked in murky river water and flattened under her car’s tires. She looked for new tools in unexpected places or made her own.

A desiccant from the agricultural industry provided a low-cost remedy for moisture. She experimented with devices such as chilli pepper roasters and bingo ball cages before customising one to gently tumble fossilised bricks of fabric from Rwanda until they broke into separate garments.

The Nyamata project – a partnership between the Rwanda National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide and PennPraxis, a research institute at the University of Pennsylvania – restored colour and form to the clothes. Now, according to Martin Muhoza, a conservation specialist, “you can imagine exactly who was wearing the textile”.

Over month-long visits to Phnom Penh, Ms Brennan led an exhaustive operation organising climate-controlled storage and training the staff at Tuol Sleng museum. Decades removed from the Khmer Rouge regime, her Cambodian collaborators brought a sense of urgency to the work.

Before mending the clothes of historical figures, she reads their biographies, even if her task is limited to a corroded zip or a faded collar

Kho Chenda, head of the museum’s conservation laboratory, said that without the evidence she and her colleagues save, Cambodia would run the risk that future generations would not believe the atrocities had taken place.

Now ammunition pouches, hand-patched linen shirts and tube skirts sit alongside the museum’s black-and-white photographs of some of the 20,000 political prisoners once held there and torture devices used to extract “confessions”.

Ms Brennan, whose father worked in foreign affairs for the US government, was born in Indonesia and lived as a child in Nepal and Bangladesh. Textile crafts grounded her peripatetic life; she learned embroidery from her Thai caretakers and batik-making and palm-weaving in middle school.

“I was wrapped and carried in batik [cloth] on my Indonesian nanny’s hip from the day I was born,” she said.

After studying art history, Ms Brennan was apprenticed to a textile conservator in Philadelphia and after 10 years founded her own practice in Washington. She says: “The work is contemplative and disciplined.”

Before mending the clothes of historical figures, she reads their biographies, even if her task is limited to a corroded zip or a faded collar. With private clients who want to preserve family heirlooms, she takes on the role of a “textiles therapist”, listening to the memories evoked by the needlepoint samplers and christening dresses.

The genocide memorials were not her first encounter with remnants of tragedy – she has treated artefacts from every major US war – but the immediacy of the violence made these assignments more difficult.

In Rwanda, she regularly handled garments that attested graphically to the killing. A dress pierced with haphazard holes suggested grenade shrapnel. A very cleanly sliced T-shirt indicated the use of a machete.

She admits: “My mind automatically filled it out with the person that was wearing it. I would have to steel myself.” Her Rwandan collaborators, many of whom were themselves survivors of the genocide, were an inspiration.

She was also guided by the example of Miyako Ishiuchi, a photographer who captured evocative images of garments that survived Hiroshima.

Brennan recounts: “After she photographs one of these textiles, she says ‘goodbye’ and ‘I’ll make sure that your memory is kept alive’.”

Ishiuchi inspired Ms Brennan to rethink the notion that a conservator must remain “detached and technical”. She allows herself to wonder about the lives hinted at by details such as names embroidered on to military caps and tiny pockets sewn into waistbands and seams.

She still thinks about a “Creamsicle-coloured” child’s dress found among the Khmer Rouge uniforms. It conjured images of a young girl “playing in the courtyard of her house off a boulevard,” she recalls, guessing that its Peter Pan collar and flared silhouette “must have been so ‘supervogue’ in 1968-69.”

An unknown number of children, including some infants, were imprisoned at Tuol Sleng, only a handful of whom survived. Conserving the dress was a small, necessary gesture for Ms Brennan, restoring a record of “a person and an era”.

She said: “It’s so distinctive, that somebody might even recognise it.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks