‘A nightmare’: How the return of the Marcos family is viewed with fear in the Philippines

Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, the son of the dictator who brutally ruled the Philippines for years and then fled with billions, became the country’s president on Thursday. Many still cannot believe the shamed family is back in power, reports Rory Sullivan

On 25 February 1986, Ferdinand Marcos, the dictator of the Philippines, fled his country in a US Air Force plane stuffed with relatives, cronies and spectacular wealth.

The toppled ruler landed in Hawaii with the possessions his family and their helpers had hastily packed, including dozens of solid-gold bars and millions of dollars in cash. This was but a small glimpse into the $10bn (£8.2bn) fortune the family were said to have amassed at the expense of the state.

Back on the ground in his newly liberated country, Boni Ilagan, who had been imprisoned and tortured for his role in the anti-Marcos resistance movement, was celebrating his people’s freedom.

“It was euphoric. We’d been fighting against Marcos for many years and the struggle was difficult, with more downs than ups. And then it happened,” the now 70-year-old said, reflecting on the moment the People Power Revolution succeeded.

In the end, the army’s disillusionment and the presence of hundreds of thousands of people on the streets brought an end to more than two decades of Marcos rule, much of which had been imposed under martial law.

For Ilagan, whose sister was killed by the Marcos regime, the past was painful but the future appeared bright. “I was high, so to speak. There was a great deal of democratic space. The new president came from our ranks. Her husband had been assassinated, so we shared the same sentiments.”

Over the intervening years, reality did not keep pace with Ilagan’s hopes.

Then, several months ago, the past collided violently with the present: the long-dead dictator’s only son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, swept to victory in the 2022 presidential election, buoyed by a disinformation campaign that coated his father’s despotism in a golden light and tarred his opponents as communists.

Marcos Jr gained more than 30 million votes to his opponent Leni Robredo’s 14 million, so the election was decisive, but it was marred by allegations of vote buying and politically motivated violence.

The Marcos restoration, which was completed yesterday with Marcos Jr’s presidential inauguration, has been in the works for some time.

The outgoing leader Rodrigo Duterte, whose daughter Sara is Bongbong’s second-in-command, facilitated the process, controversially allowing Marcos Sr, who died in 1989, to be buried in the country’s Heroes Cemetery in 2016. That same year, Marcos Jr unsuccessfully ran to become vice president, a sign of the family’s desire to play a leading role in Filipino politics once again.

Although Marcos Jr’s rise to the presidency was not fully unexpected, it is still a major blow to those who survived the brutality of his father’s dictatorship and lost loved ones in the struggle to oust him. Several told The Independent about their fears for Bongbong’s presidency, but also expressed optimism that younger generations of human rights activists had taken up the baton of resistance.

“Marcos Jr becoming president is a nightmare. It’s unimaginable, it’s surreal,” Ilagan said.

“The unthinkable has happened. One day soon I really have to come to terms with reality. But my reality is that I’m no longer young and I can no longer do the things I could do, so I feel a certain amount of despair, hopelessness even. But I realise that a lot of young people have been awakened by the developments,” he added.

The same thing happened to him and others in 1969, when Marcos Sr won a second term in an election that was characterised by violence and corruption.

“People were living in poverty while Marcos and his cronies were awash with wealth. That was also the time when there was a real awakening among the young people of the Philippines – students, union leaders, peasant leaders, the urban poor,” Ilagan said.

After a brief stint in student campus politics, he was put on the military’s blacklist and decided to go underground in 1971. Three years later, the army caught up with him, arresting him and two friends who were also involved in the resistance’s media operations.

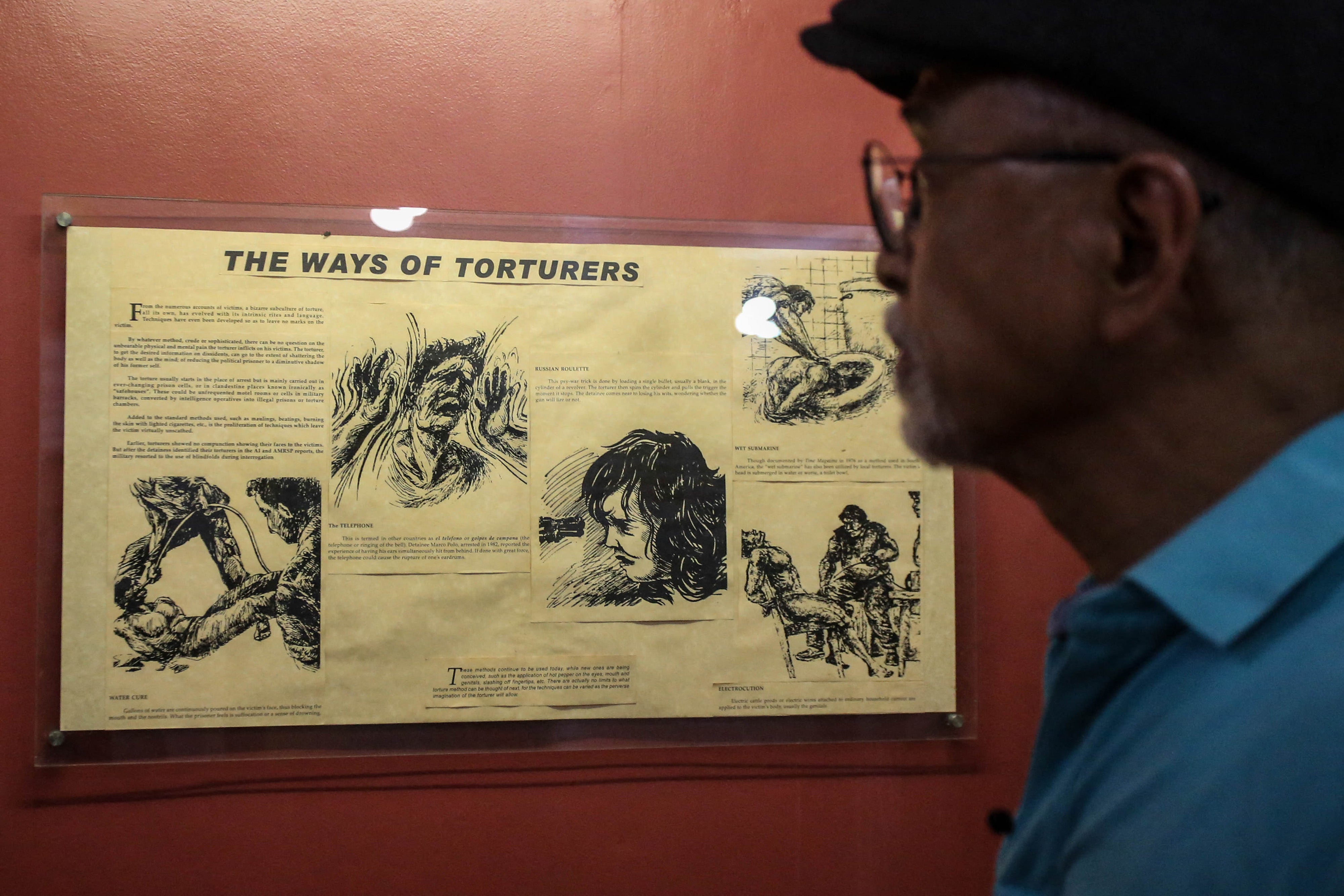

Ilagan was taken to Camp Crame, the national headquarters of the police, where he was tortured. “The first week of the detention was the worst. It was when they really employed violent methods of torture. They inserted bullets between my fingers and squeezed my hand so tightly. I thought the bones of my fingers would crack.”

His captors also kicked and punched the then 23-year-old, causing him to pass blood. Some methods, however, were even more invasive.

“At one point they asked me to pull down my trousers and my underwear. They then inserted a stick through my penis. They also applied a hot iron to the soles of my feet.”

The 70-year-old also recalled a time when he was escorted out of the camp and was ordered to run. “I knew that, had I done that, they would have shot me,” he said. Instead, he hung on to the vehicle and the commotion alerted the local neighbourhood, making the guards uneasy.

In the summer of 1974, he was unexpectedly released, the result of some string-pulling by his mother. But the joy of freedom was soon displaced by a deep loss.

Against his better judgement, Ilagan agreed to meet his younger sister, who was also part of the resistance. After she sent a letter asking him to find a new safe house for her and her friends, they arranged to see each other for a second time.

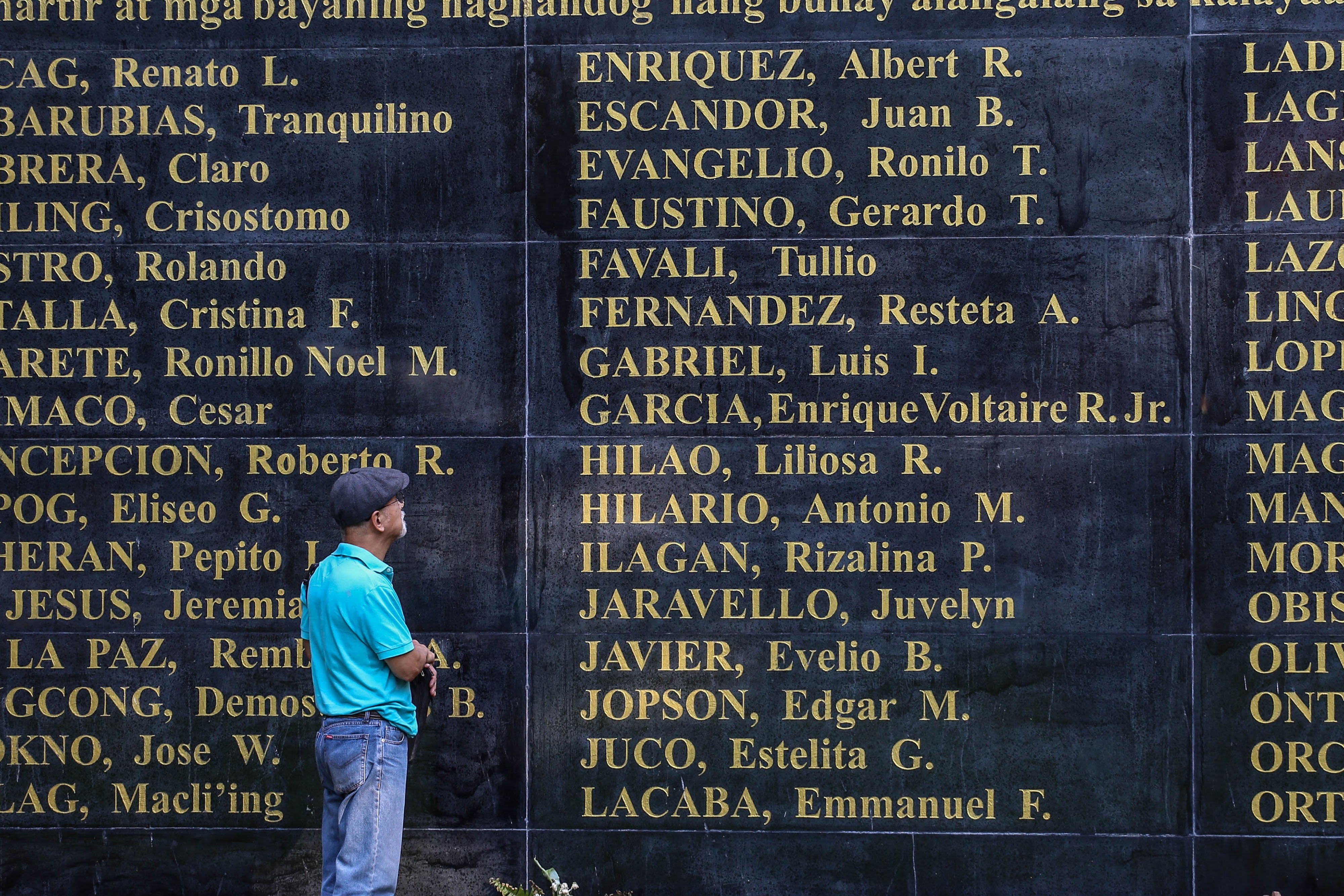

“On that appointed day, I waited and she never came because she had already been abducted by the military,” he said. In the largest single abduction, Rizalina Ilagan and nine others, who came to be known as the Southern Tagalog 10, were seized and then disappeared.

The family’s search in police stations, military camps and hospitals was futile. “After a few months, two were found dead in a ravine. Another one was exhumed in a common grave in another province. Three of the 10 surfaced dead; the other seven have not been found to date,” Ilagan said. His parents pleaded with him not to continue his activism, but understood that he would not stop.

Judy Taguiwalo, a social worker and activist who has served in government, was also detained and also lost people close to her under the Marcos regime.

The 72-year-old was detained in 1973, broke out of prison the following year, only to be recaptured by the authorities in 1984. During her second spell of incarceration, which ended with Marcos Sr’s fall from power, she gave birth to her daughter.

Taguiwalo and her fellow political prisoners found the victory of the People Power Revolution bittersweet. “We cried and remembered those of our colleagues, our friends, our classmates, our comrades who died fighting the dictatorship. Many of my friends died in prison or disappeared during martial law.

“It was part jubilation because finally the dictator was out but also sadness because of remembering those who had given up their lives.”

When Marcos Jr was declared president-elect 36 years later, Taguiwalo was angry. “A Macros restoration was not something we expected after what the country went through for 21 years under the Marcos regime,” she said.

“It was a nightmare that this could happen. But also a realisation that not much had changed since the Marcoses were ousted in 1986.”

Several young people wrote to her after the election to apologise for not being able to stop the rise of another Marcos after all his family had done to her and others. Taguiwalo said she was touched by their kind words and was encouraged by their activism.

Taguiwalo believes democratic freedoms in the Philippines are now under greater threat, citing the recent closure of independent media sites and the chief of police’s warning that protests will not be tolerated on the day of Marcos Jr’s ascension to the presidency.

The veteran campaigner sees the choice of site for yesterday’s inauguration as important, noting that she and other students protested in the same spot against Marcos Sr in January 1970, before being violently dispersed.

“It’s intentional on Marcos Jr’s part: he’s reclaiming the site. It’s where students first rose against his father,” she said.

Ivan Sucgang, chair of the League of Filipino Students (LFS), also thinks the political climate will worsen under Marcos Jr, saying there had already been signs of a recent crackdown on freedom of assembly.

The 23-year-old political science student said he was targeted by police in “Freedom Park” on 25 May during a demonstration against the restoration of the Marcoses.

“Freedom of speech should be most protected there. But we were faced with battalions of riot police. They showered us with water cannons and 14 protesters including me were injured,” Sucgang said. He is still unable to move his right foot after it was hit by a riot shield, he added.

Although he is worried that the police and the military “will be emboldened to commit more violent acts against protesters”, he remains optimistic because “crisis always generates resistance from the Filipino people”.

Christian Gultia, communications officer of the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA), has similar concerns, which have been exacerbated by the announcement that extra funding will be given to the police and the military.

“My worst fear is of course the continuation of attacks against activists. We know the administration is going to be ruthless,” he said, claiming the new government would employ “more sophisticated means of getting away with human rights violations” than the previous government did.

For Ilagan and Taguiwalo, these are worrying times but, despite the gloom, they find grounds for optimism.

“There’s hope because here the young people are keeping up the fight,” Ilagan said.

“When I started in the movement in the late 1960s, the movement was really weak. The organisations were small, we were few. But we were able to get stronger as the years went by. I think we will be able to achieve what we’ve been dreaming for our country. It just might not be in my lifetime.”

Taguiwalo seconds this opinion. “Tyranny is not forever,” she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks