Trump’s assassination of Iran’s top general Qassem Soleimani will likely weaken his hand in Iraq

With hostilities between the US and Iran sure to escalate, the Iraqi government may no longer support the presence of American troops on their land, writes Patrick Cockburn

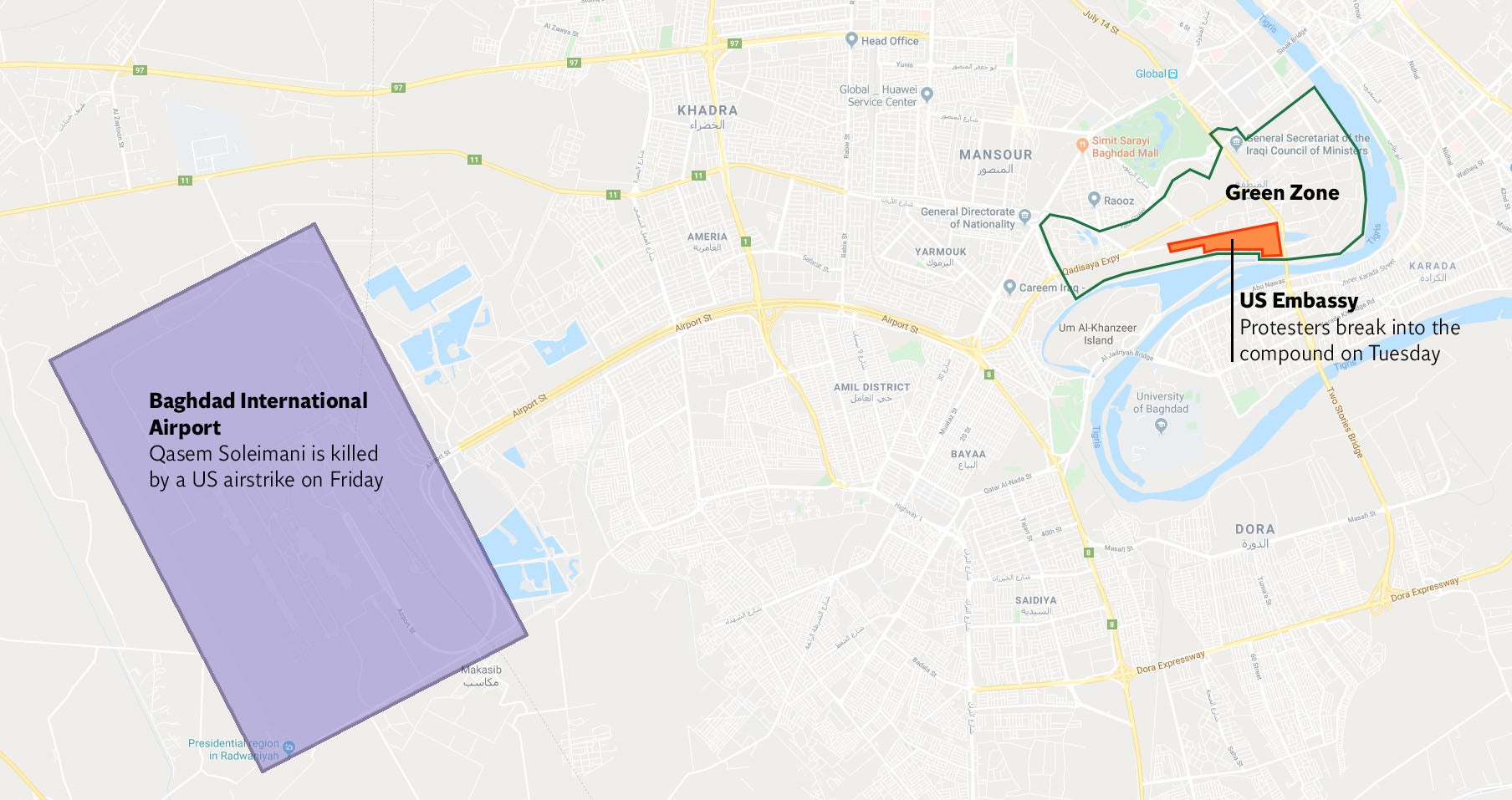

The assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the most famous Iranian general, in a US airstrike as he left Baghdad airport ensures an escalation in hostilities between the US and Iran. The most serious consequence is likely to be that the Iranian leadership will use the killings to pressure the Iraqi government to expel US forces from Iraq.

The Iranian government will not be the only ones looking to retaliate. Among those who died in the car in which Major-General Soleimani was travelling was Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the head of the pro-Iranian paramilitary group Kata’ib Hezbollah, whose militants could well resume their assault on the US embassy in the Green Zone in Baghdad, where they staged a limited incursion earlier this week. Crucially, the Iraqi security forces stood aside, underlining the vulnerability of the American embassy and all US bases in Iraq, where 5,000 US troops are stationed.

The most likely Iranian reaction will be to step up its efforts to end the US military presence in Iraq, acting through the Iraqi government and the pro-Iranian paramilitary forces. The Iraqi leadership, which normally balances between Washington and Tehran, was already angry that the US had unilaterally attacked Kata’ib Hezbollah bases on Sunday, killing 25 of its fighters.

The US forces are supposedly in Iraq for the sole purpose of fighting Isis in collaboration with the Iraqi armed forces. Using that military presence to kill opponents of the US is clearly a gross infringement of Iraqi sovereignty. The US airstrikes on Sunday were not only condemned by Iraqi political leaders, but by grand ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the vastly influential spiritual leader of the Shia in Iraq. He has also condemned the killing of Soleimani.

The killings in the cargo area of Baghdad airport represent a far greater assault on Iraqi sovereignty than anything that happened previously. The Iranians might see it as being in their long term interests to let the Iraqi government and parliament push the US out of the country rather than directly attacking US interests themselves.

At the same time, the Iranians and the rest of the world will have been caught by surprise. Previously, Mr Trump had responded cautiously to serious Iranian provocations, notably the shooting down of a US drone over the Gulf in June, and the drone and missile attack on Saudi oil facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais in September that was blamed on Iran. It is unclear why Mr Trump should have over-reacted so spectacularly to a Kata’ib Hezbollah rocketing of a US base in Kirkuk a week ago that killed an American contractor and several Iraqis.

The US retaliatory airstrikes that killed 25 members of Kata’ib Hezbollah had already been criticised as excessive and politically counterproductive. They came at a time when Iran was losing popularity and influence in Iraq because it supported – and most probably initiated – the shooting dead of hundreds of Iraqi demonstrators protesting against government corruption and lack of jobs.

Thanks to pro-Iranian paramilitary snipers firing directly into the crowds, the protests had escalated into a demand for the Iraqi government to go and protesters had targeted Iran as the chief orchestrator of the repression. General Soleimani was reported to be the man who had given the orders for the crackdown beginning on 1 October, possibly seeing the protests as a US plot to overthrow the Iraqi government by a “velvet revolution” as in Egypt in 2011 and Ukraine in 2014.

Soleimani, if he did think this, was certainly mistaken. The brutality of the repression generated the very anti-government movement – close to a mass uprising – that it was supposed to avert. Moreover, the protesters increasingly saw Iran as the foreign hand behind the killings. Iran, until recently seen by Iraqi Shia as their great ally against Saddam Hussein and Isis, became unpopular and its consulates in the Shia holy cities of Kerbala and Najaf were burned by angry crowds.

These developments were the gravest threat to Iranian influence in Iraq since the US and British invasion in 2003. Astonishingly, Mr Trump may have unwittingly saved the crumbling Iranian position in Iraq by carrying out what will be portrayed as the martyrdom of Soleimani, Muhandis and other less well-known members of Kata’ib Hezbollah.

The Iraqi government will now have to show itself as defending the national independence of Iraq under Shia rule against US actions. It will be able to denigrate protesters as being covertly allied to the US and claim that the Shia community in general is under threat. One of the reasons the street protests have gained momentum over the last three years is that the defeat of Isis removed what the Shia masses had seen as an existential threat. This enabled them to focus on – and seek to displace – their own kleptocratic leadership. By threatening Shia predominance in Iraq, by treating it as if it was a country under US occupation, Mr Trump has ensured that accusations of Iranian interference become a secondary consideration.

The death of Soleimani, the head of the Quds Force of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards since 1998, is unlikely to be a crippling blow to Iranian operations in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. He was judged to be a skilful practitioner of Iran’s brand of militarised foreign policy, building up powerful pro-Iranian paramilitary forces rooted in local Shia communities. But he appears to have misjudged the nature of the latest Iraqi protests and generated a vast problem for Iran where none existed before.

Possibly, Mr Trump was misled by the positive reception he got when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of Isis, was likewise killed by US forces in Syria last October. But Baghdadi was the universally execrated head of a defeated organisation whose personal demise was symbolic of a US victory. Turning Soleimani and Muhandis into martyrs is likely to strengthen the Iranian position in Iraq rather than weaken it.

Precisely how the consequences of the assassinations will play out remains uncertain, but the struggle for Iraq between the US and Iran will surely intensify. This is not to the advantage of the US, which has much the weaker hand in the country. As the International Crisis Group put it earlier this week: “Directly challenging Iran’s role in a theatre where Tehran has far greater influence is almost certain to end badly for Washington.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks