China’s emissions have stopped rising for two years. Is this the start of a decline?

Whether the current plateau becomes a sustained decline will depend largely on decisions in the next five-year plan, due in March

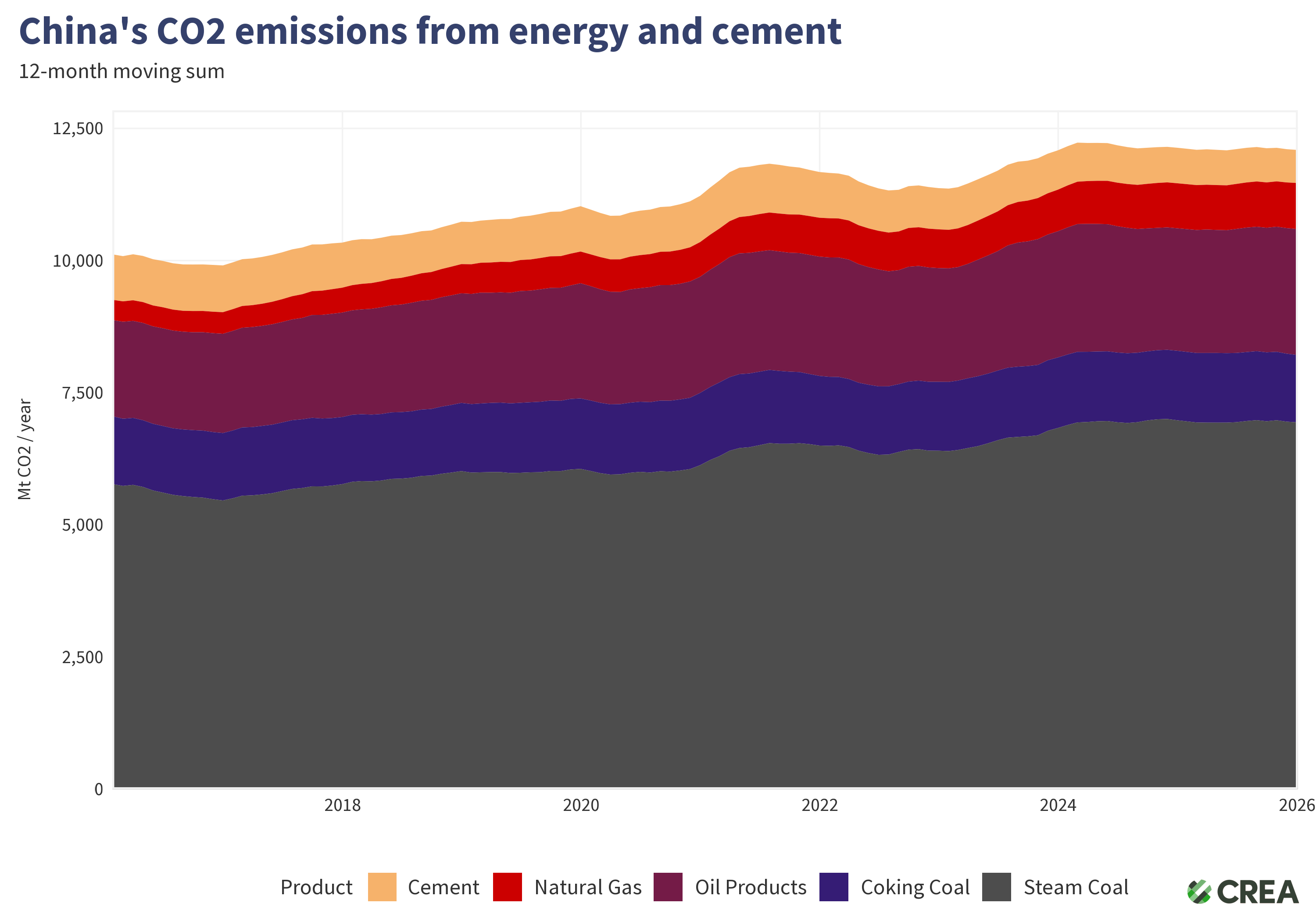

China’s carbon dioxide emissions have now been flat or falling for nearly two years, raising fresh questions over whether the world’s biggest emitter has reached a turning point.

Emissions fell one per cent year-on-year in the final quarter of 2025 and likely to have declined by around 0.3 per cent over the year as a whole. That keeps them slightly below the record levels reached in early 2024, when China’s emissions last peaked.

The figures come from new analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air for Carbon Brief, which tracks monthly energy production, fuel use, and industrial output to estimate near real-time emissions trends. This is the longest such stretch on record that has not been driven by an economic slowdown in the country.

“I think it's clear that emissions have plateaued, but there is a question mark about the next couple of years since the government is officially only targeting a peak in coal consumption around 2027, and in general even a plateau means there could be year-to-year ups and downs due to seasonal factors,” Lauri Myllyvirta, the centre’s lead analyst, told The Independent.

The stabilisation has come despite continued growth in electricity demand. Power consumption rose by 520 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2025. But new clean generation more than covered that increase. Solar output rose 43 per cent year-on-year, wind generation 14 per cent, and nuclear eight per cent, together supplying roughly 530TWh of additional electricity – slightly more than the growth in demand.

As a result, coal-fired generation fell by 1.9 per cent and overall power-sector emissions dropped by 1.5 per cent. Emissions from transport declined by three per cent, while cement and other building materials fell by seven per cent. Metals also recorded a three per cent decline.

Asked what was driving the plateau, Mr Myllyvirta said: “Rapid growth in clean energy and electrified transport are the key factors.

“Declining demand for cement and steel is also significant, and the drop in steel emissions should accelerate if the structural shift to more recycled steel and electric arc steelmaking happens as targeted – it has been badly off track due to overcapacity in coal-based steelmaking.”

Another notable shift came in energy storage. China added 75 gigawatts (GW) of storage capacity in 2025, while peak electricity demand increased by 55GW. It was the first year that storage growth outpaced peak demand growth, potentially reducing the need to rely on new coal and gas plants to meet short bursts of high demand.

However, the overall picture remains finely balanced. The annual decline in emissions was marginal. Fossil fuel emissions edged up by 0.1 per cent in 2025 and were only offset by a sharp fall in emissions from cement production.

Emissions are only slightly below the early 2024 peak. A modest rebound could see them exceed that previous high.

The chemicals industry remains the main source of growth. Emissions from the sector rose 12 per cent in 2025, driven by increases in coal and oil use. Although chemicals account for around 13 per cent of China’s total emissions, the pace of expansion is having an outsized impact. Without the rise in chemicals, total emissions would have fallen by an estimated two per cent rather than 0.3 per cent.

Whether the current plateau becomes a sustained decline will depend largely on decisions in the next five-year plan, due in March.

“Since policymakers do not appear ready to commit to cutting emissions over the next five years, the most important thing would be removing barriers to continued growth in clean energy, especially making the operation of power grids and coal power plants more flexible and using energy storage to accommodate much higher shares of solar and wind in the grid. It will also be necessary to start limiting the growth of coal power capacity,” Mr Myllyvirta said.

He added that recent clean-energy additions could help prevent a rebound in the short term. “One positive thing is that the year-end surge in clean energy additions will continue to drive up clean power supply this year, so there is a good chance that there is no rebound in emissions before the 2027 coal peak.”

China’s official position remains that carbon dioxide emissions will peak “before 2030”.

For now, the data suggest a plateau. Whether it proves to be the start of a lasting decline will become clearer over the next two to three years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks