‘Last Supper’ painting featuring nude Mata Hari removed from exhibition after protests

Artist says painting was not intended to be a religious provocation

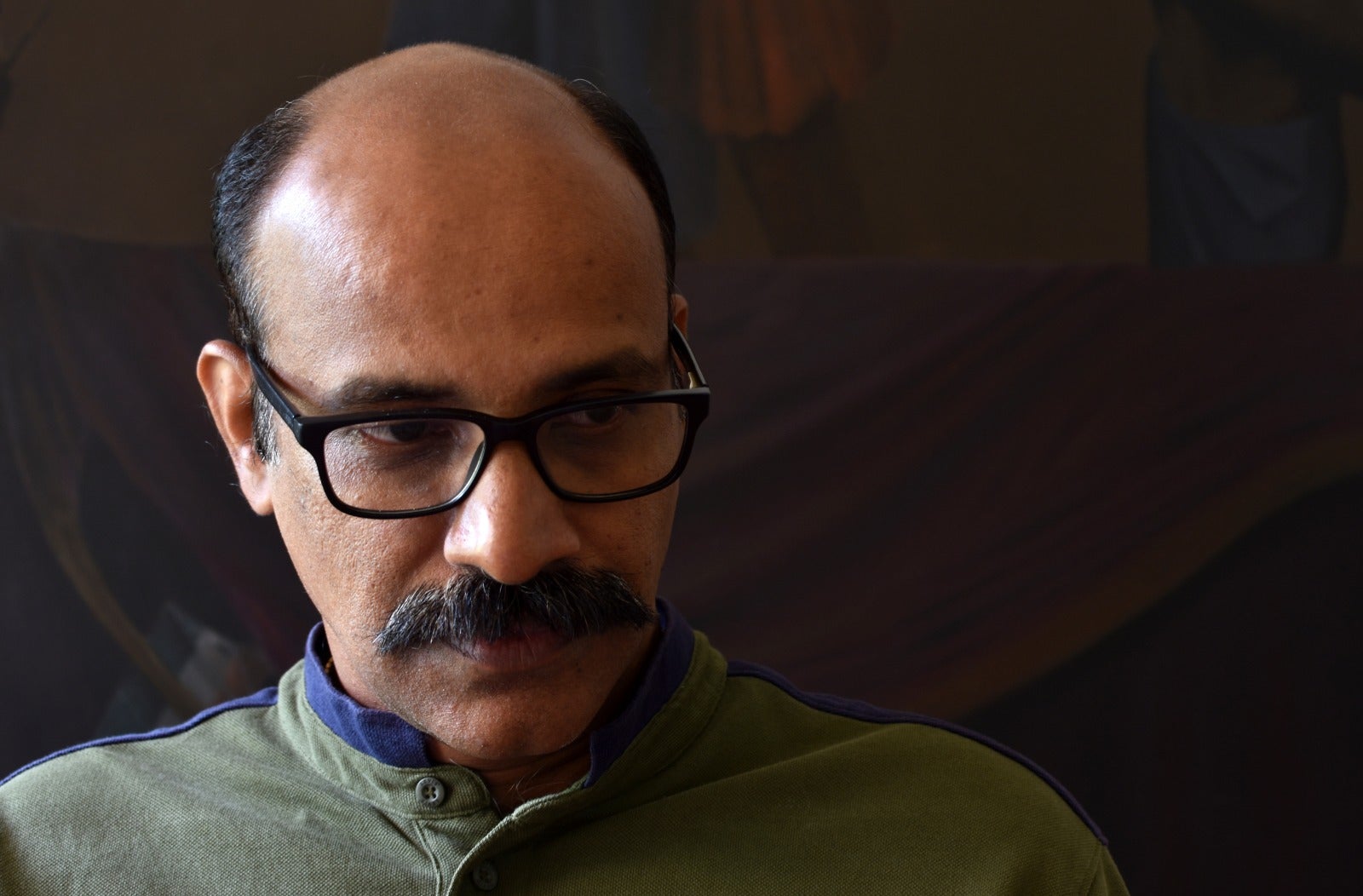

An Indian artist has defended his controversial version of The Last Supper after it caused a major event in India to be suspended by authorities.

Supper at a Nunnery by Tom Vattakuzhy was displayed as part of Edam, a parallel exhibition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale.

Christian groups objected to the work, arguing that its composition clearly echoed The Last Supper and that placing a nude female figure in the position traditionally associated with Jesus Christ was insulting to their religious beliefs.

The biennale, founded in 2012, is the country’s largest international contemporary art exhibition, held across heritage sites, warehouses, and public spaces in the coastal city of Kochi in Kerala.

Edam, held at three venues and involving 36 artists, was aimed at showcasing the “diverse art practices from Kerala”. It was at one of these that Vattakuzhy’s image elicited objections.

Supper at a Nunnery depicts Dutch exotic dancer Mata Hari, who was executed by French authorities during World War I on charges of espionage, seated nude at the centre of a long table surrounded by nuns.

It was conceived not as a standalone artwork but as part of a practice where paintings functioned as visual responses to literature, Vattakuzhy said, adding that he had made these “story paintings” for literary magazines in an attempt to reach audiences beyond galleries.

“When a painting appears in a gallery, only a niche crowd will come,” the artist told The Independent.

“But when it appears in a periodical, it reaches people in their homes and they see how an idea can be transformed into a visual form.”

Supper at a Nunnery emerged in response to a play by Malayalam writer C Gopan which depicts the final night of Mata Hari’s life, when she is sent to a nunnery and shares her last meal with nuns before her execution.

“The germination of the painting comes from the corresponding story and then I develop it in my own way,” the artist said, referring to the play, translated as The Unnatural Death of a Soft-Bodied Soul. “There is an umbilical connection with the story, in its content and its spirit.”

Vattakuzhy, whose work often draws on literature and lived experience to explore vulnerability and suffering, said he was deeply affected by Mata Hari’s story and in particular the accounts of her final moments.

“As per the normal procedure they wanted to cover her face, but she refused. She stood before the firing squad very calm and composed, with a beautiful smile,” the painter said. “To stand in front of death with a smiling face is something that really touched me. Before they fired on her, she sent a flying kiss to the soldier. Doesn’t that tell you something?”

Vattakuzhy said the story resonated deeply with him. “I was really moved by her life,” he said. “I should confess that I’m quite an emotional person. Maybe because I am an artist, I can’t help it.”

Although Christians make up only 2-3 per cent of India’s population, they number roughly 18 per cent in Kerala, according to the 2011 census.

Vattakuzhy’s work drew objections from several church bodies as soon as it went on display.

Tom Olikkarott, a public relations officer for the Syro-Malabar Church, condemned the “distorted depiction of The Last Supper”, which he said was a “violation of basic respect towards religious faith”.

In a letter to state authorities, the Kerala Region Latin Catholic Council criticised the image as “inappropriate”, and asked for the “withdrawal and removal of the offensive replica from public display”.

The venue displaying Supper at a Nunnery was temporarily closed on 30 December, with organisers citing concerns about security and public order.

After meeting with local officials, the Kochi Biennale Foundation said in a press release that the artist and the exhibition’s curators had jointly decided to withdraw the painting “respecting public sentiments and in the interest of the common good”.

The exhibition space reopened on 5 January, without Vattakuzhy’s Supper at a Nunnery.

The curators had previously released a statement standing by the artwork, saying they did not believe the painting warranted removal.

“Taking down the artwork would amount to restricting artistic expression and could be perceived as an act of censorship, which is contrary to the principles of artistic freedom and cultural dialogue the exhibition seeks to uphold,” they said.

Vattakuzhy said he had been left feeling “demoralised and dispirited” by the protests. He himself was raised in a Christian family and considered himself “deeply influenced by Christian values”, he added.

This is not the first time Supper at a Nunnery has attracted controversy. In 2016, the artwork appeared in the Malayalam literary magazine Bhashaposhini and triggered protests by Christian groups. In response, the magazine’s publishers withdrew the issue from circulation and issued a public apology, saying the illustration had “hurt religious sentiments”.

Vattakuzhy said that episode had left a lasting impact on him and he had been cautious about engaging with themes connected to Christianity ever since. Even so, he said, neither he nor the curators expected the work to provoke a similar response at the biennale.

“I didn’t expect this, because when it first appeared it went out to a larger audience in a magazine. This is a biennale venue, it is a special venue meant for an art crowd,” he said.

“I cautioned the curators that there was some history attached to this work, but they also did not anticipate that such a situation would arise, especially in a biennale venue. A biennale venue is supposed to have a certain level of care and protection, as one of the premier international events.”

The biennale is one of South Asia’s most widely attended art festivals and its prestige can be gauged from the fact that previous editions have hosted the likes of Ai Weiwei, Ernesto Neto, Anish Kapoor, Jitish Kallat, and Shilpa Gupta.

This year’s edition began on 12 December and is set to continue until 31 March 2026.

Reflecting on the objections, Vattakuzhy said they revealed a rigid reading of religious imagery that left little room for interpretation.

“They see Christ only in the outer appearance. They cannot think beyond that,” he said.

“They say it’s iconography, reminiscent of The Last Supper. Why did I paint a setting that reminds of The Last Supper? And then, in the place of Christ, I painted a woman. That they could not digest.”

That reading, he said, was not his own. “I see Christ in people who are deprived, who are made scapegoats, who are suffering,” he said. “For me, Christ isn’t about outward appearance. It is about compassion, love and empathy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks