Chinese museum embroiled in corruption scandal after priceless artwork mysteriously appears at auction

Painting once deemed a forgery and ‘transferred’ by museum appears at auction at an estimated price of £9.3m

A Ming dynasty painting that reappeared at an auction last year has exposed decades of corruption and “serious violations of duty” at one of China’s most prominent state museums.

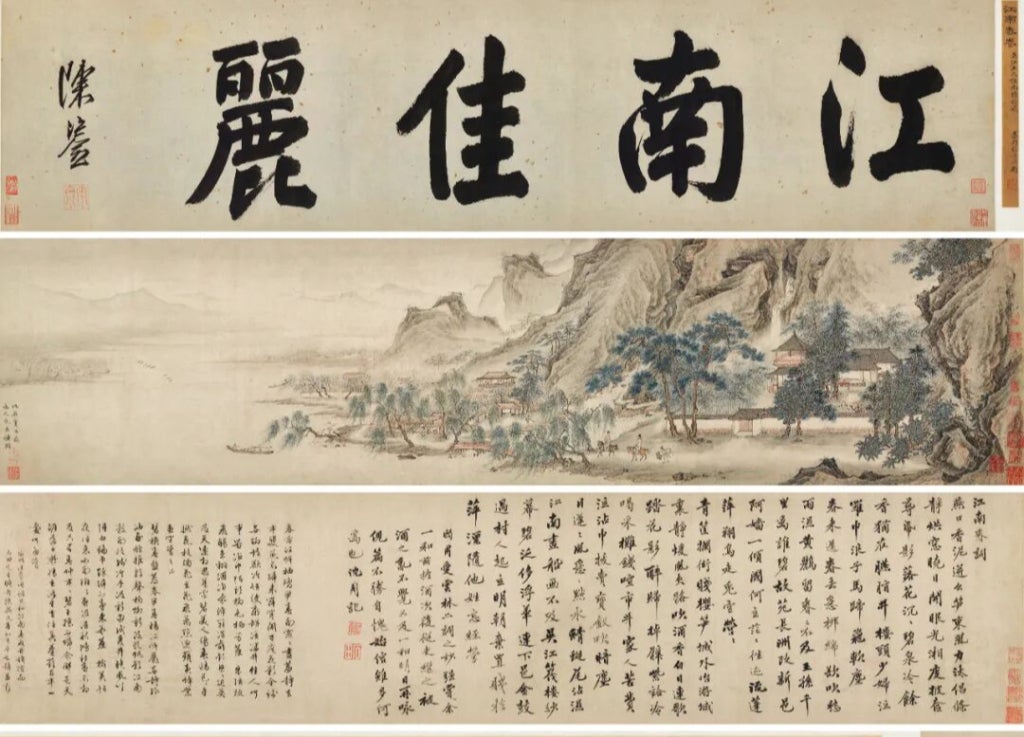

The work in question is a handscroll titled Jiangnan Chun, or Spring in Jiangnan, which has been attributed to the 16th-century court artist Qiu Ying. The painting had not been seen in public since 1959, when the family of industrialist and celebrated collector Pang Yuanji donated 137 works of painting and calligraphy to the Nanjing Museum.

However, in May last year, the painting appeared in a preview catalogue for China Guardian Auctions – a mainland Chinese auction house – with an estimated price of 88m yuan (£9.3m), which immediately led to alarm among Pang’s descendants.

Pang Yuanji’s great-granddaughter, Pang Shuling, recognised the nearly 23-foot scroll at once from the 12 Xuzhai seals of her family collection.

“My great-grandfather’s 12 Xuzhai seals, the original sandalwood box. It’s my family’s property. I saw it when I was a child. It felt so familiar,” she told Caixin Global.

She alerted the National Cultural Heritage Administration – the state body responsible for the national protection of cultural relics – and asked for the painting’s ownership history. Within days of her complaint, the auction house withdrew the lot.

After Pang raised questions about the scroll’s provenance, she filed legal action seeking clarity over the 1959 donation. In June 2025, a court ordered the Nanjing Museum to conduct an inventory of the Pang family’s donated works, according to the South China Morning Post.

During the court-supervised review, investigators determined that five paintings from the original 137-piece gift – including Spring in Jiangnan – were no longer in the museum’s possession.

At the time, Nanjing Museum defended its actions by pointing to an expert appraisal conducted in 1961 and 1964, which had determined that Spring in Jiangnan and the four other works from the Pang donation were forgeries.

On that basis, the museum later removed the works from its formal collection and “transferred” them out in the 1990s, treating them as items that did not merit preservation as state cultural relics.

However, the conditions of the appraisal drew scrutiny. The museum’s statement said the review took place over 70 days, where specialists examined more than 51,000 objects. This approach, according to the team, was a “last resort adopted during a special time”.

Pang filed a further lawsuit against the Nanjing Museum, seeking the return of all five paintings from her family’s 1959 donation that had been removed from the collection. The museum argued that ownership transferred to the state at the time of donation and that the family therefore had no legal right to reclaim the works.

“The Nanjing Museum’s unilateral determination that five items were forgeries has seriously damaged the reputation of my great-grandfather and father. If they believed there were forgeries, they should have notified us immediately so we could jointly verify their authenticity. If we could not reach an agreement, and the Nanjing Museum decided not to collect them, we had the right to reclaim them,” Pang told The Paper, according to a translation of the report.

In December, the National Cultural Heritage administration formed a working group to dig deeper, and Jiangsu provincial authorities launched a parallel investigation.

The findings of this investigation, released this week, paint a stark picture.

Investigators concluded that the five missing paintings from the Pang family’s 1959 donation were illegally transferred in the 1990s and early 2000s to the Jiangsu Provincial Cultural Relics general store and sold, resulting in the loss of state-owned cultural assets, according to a report in Global Times.

They found that the then executive deputy director of the Nanjing Museum failed to follow required procedures and “unlawfully signed off” on transfer applications despite regulations prohibiting the unauthorised sale or disposal of museum collections.

Once the scroll arrived at the relics store, it did not remain in storage. A store employee in 1997 altered its listed price from 25,000 yuan (£2,647) to 2,500 yuan (£264), and arranged for the work to be purchased by an accomplice at 2,250 yuan (£238) under a generic name. This accomplice arranged another sale of the scroll, along with two other paintings, to a private collector for 120,000 yuan (£12,707).

A sale record from 2001 showed that the work was sold for a mere 6,800 yuan (£720) and identified the work as an imitation, reported Xinhua.

Over the next two and a half decades, the scroll passed through multiple private owners and dealers before it surfaced in the auction in May 2025.

China’s 1986 Measures for the Management of Museum Collections prohibit the sale of objects from state museum holdings.

The provincial probe found that the five missing paintings from the Pang donation were illegally transferred and sold, resulting in the loss of state-owned cultural assets.

Authorities have held 29 individuals responsible in connection with the scandal. Five have since died, while the remaining 24 are facing disciplinary or legal action. The employee identified in the official findings as allegedly having facilitated the unlawful sale of Spring in Jiangnan, is also under investigation for “serious disciplinary and legal violations,” according to Xinhua.

Spring in Jiangnan was returned to the Nanjing Museum’s painting and calligraphy vault on 29 December 2025. Of the other four works identified as missing, three have since been recovered and returned, while one remains unaccounted for and under investigation.

In a public apology, the museum acknowledged “institutional deficiencies and management disorder” and admitted it violated regulations when removing and transferring the works.

“We failed the donor’s trust and hurt the feelings of his family,” they added. “In the wake of this painful lesson, our museum is determined to rise from the ashes with firm resolve and concrete actions to rebuild our image and restore public trust.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks