Forbidden gates swing open

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY CHINA DAILY, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

Meridian Gate towers above the entrance to the Palace Museum in Beijing, China’s imperial palace from 1420 to 1911 and also known as the Forbidden City. During the imperial years, numerous royals, high officials and nobles walked through this gate, which stands for solemnity, ritual and order. They stepped into a place closed to outsiders, a place in which the course of their own destinies — and often the fate of the country — was shaped.

In October 1925 the Palace Museum was established, unlocking the gates for the public and marking the beginning of a story about custodians devoted to safeguarding and extending an unbroken civilisation.

A century later tourists ascend the Meridian Gate Galleries, a privilege that was unimaginable even for most high officials who passed the doorway in ancient times. Here the exhibition A Century of Stewardship: From the Forbidden City to the Palace Museum opened on 30 September, and runs until the end of the year.

More than 200 carefully chosen exhibits, including paintings, calligraphic works, jade, bronze ware, gold ware, porcelain and architectural components, are on view.

A half-day tour of its three galleries is akin to undertaking millennia time travel.

“Cultural relics are the best records of civilisation,” said Xu Wanling, chief curator of the exhibition. “Through relics we want visitors to see those historic moments and the people behind them.”

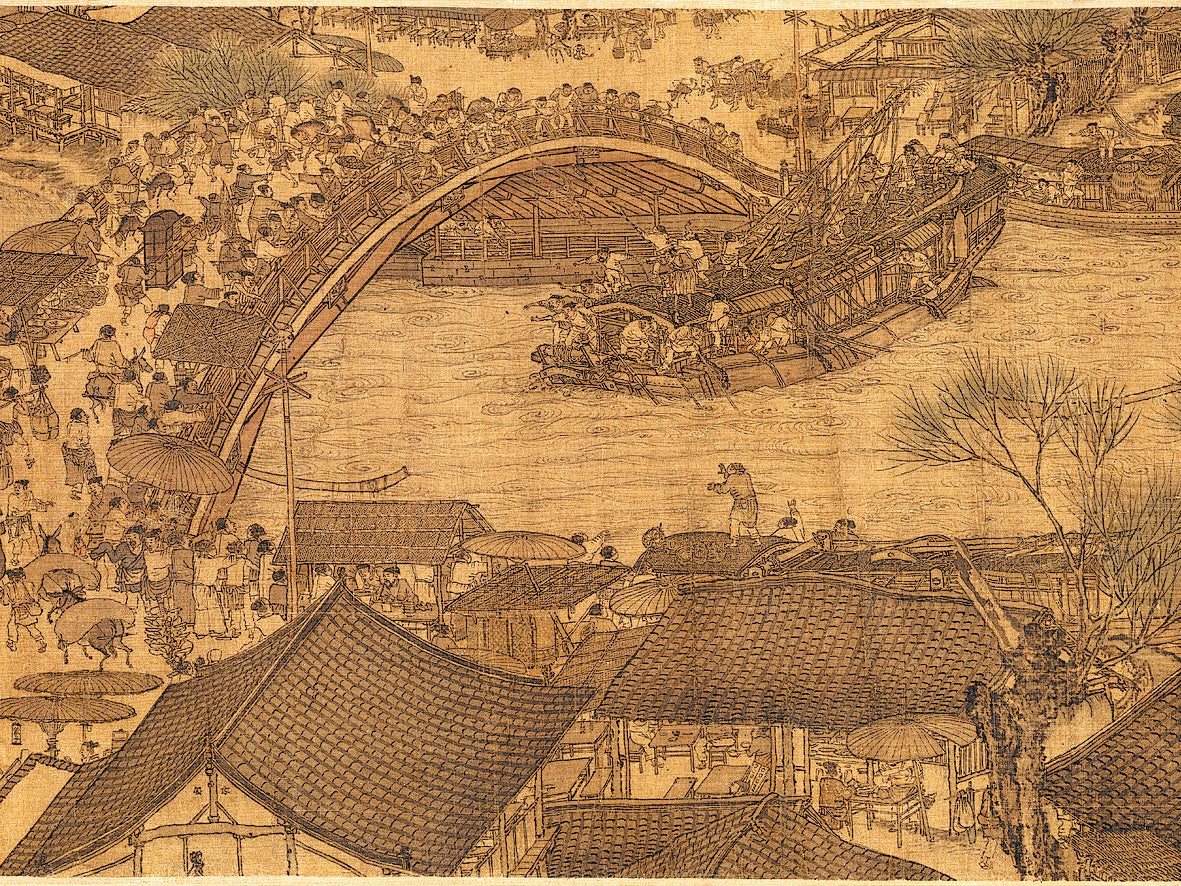

One monumental treasure on view, and perhaps the most famous Chinese painting, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, was unrolled for the first time in a decade.

This silk scroll, created by Zhang Zeduan of the imperial painting academy of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), and more than 16 feet long, depicts the flourishing landscape of the national capital of Dongjing (present-day Kaifeng, Henan province) through vivid portrayals of about 600 figures, 100 houses, 25 boats and countless details of urban life.

Seals of nearly 100 collectors, impressed over centuries, testify to the painting’s journey through history.

The scroll was lost during the war that ended the Northern Song, stolen from the palace, passed from one literati’s hand to another and from some powerful minister’s residence to the next, before eventually entering the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) royal collection in the late 18th century.

However, turmoil returned. The last emperor Puyi, who continued to live in the Forbidden City in the 1920s after the monarchy fell, managed to get the painting out of the palace again. He later took it, along with many other relics, to Changchun, Northeast China, where he presided over a puppet regime under Japanese occupation. Many assumed the painting was lost forever during the chaotic end of World War II.

Against all odds it resurfaced in 1950. Cultural relic researchers found it in a wooden case abandoned by Puyi when his puppet state collapsed. The painting later returned to the Forbidden City, intact.

Another highlight is a Tang Dynasty (618-907) guqin (an ancient Chinese plucked seven-string musical instrument) with the resounding name Dasheng Yiyin, or “lingering sound of the great sage”.

When it was first found a century ago in the Qing royal inventory, it was registered merely as “a broken guqin” because of its poor condition. Its value was only recognised more than 20 years later. After restoration in 1949, it regained recognition as a celebrated Tang-era masterpiece.

In the eastern gallery of Meridian Gate stands a bronze square jar with lotus and crane decoration, or Lianhe Fanghu, at the centre, dating back to the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), or the age of Confucius. It reflects a time when rituals shifted and old hierarchies faltered. Unearthed in 1923 from a tomb in Henan province, it was allocated to the warehouse of the Palace Museum in 1950.

Today, digitised editions of many highlights appear on screens with glasses-free 3D effects. Modern visitors may take the wonders of such technology for granted, but for any visitors stepping into the Forbidden City for the first time 100 years ago, the visual impact of these long-hidden cultural relics would have been overwhelming.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks