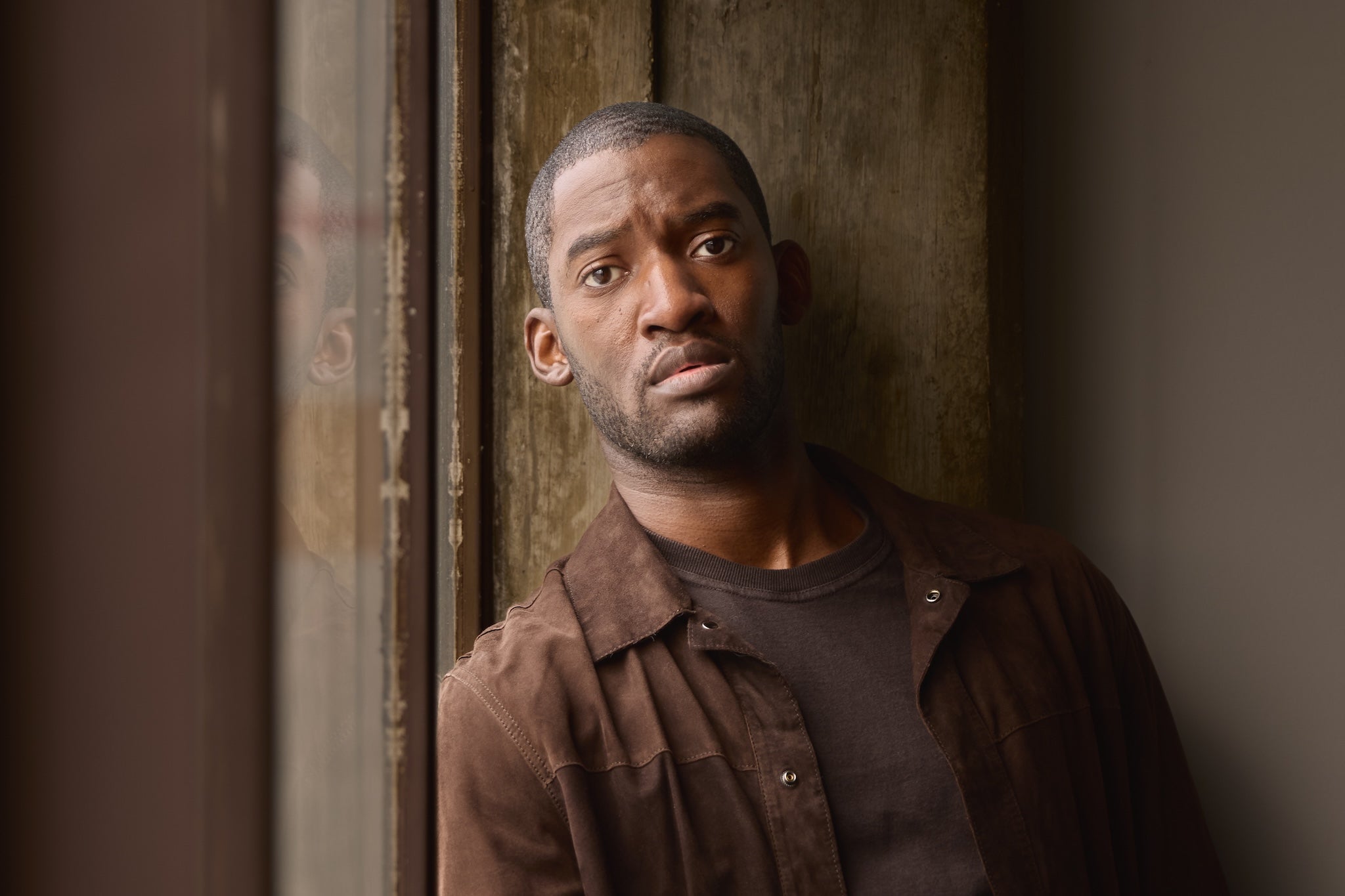

Malachi Kirby: ‘The cameras were off at this point, but I was shaking’

After roles in everything from ‘EastEnders’ to ‘Black Mirror’, the actor is now going head-to-head with Stephen Graham in the second round of ‘A Thousand Blows’. He speaks to Annabel Nugent about channelling trauma, on-set therapists, and his funny side

There is something about my face that makes people want to see me cry,” says 36-year-old Malachi Kirby, who has made a career out of brooding and breaking down in shows like Black Mirror, Roots and Small Axe. Looking at him now, his robust cheekbones and robust-er jaw, I wonder why that might be. Probably there’s something about seeing immovable strength undone by a stroke of sadness – like watching a trickle carve itself into the side of a mountain and become a raging river.

“It’d be nice to actually have fun on set for once,” Kirby laughs, giving a quick flash of pearly teeth. We’re speaking in a suite in an upscale London hotel; he’s on the sofa, grazing on a bowl of nuts. For now, fun will have to wait. Kirby’s role opposite Stephen Graham in A Thousand Blows as Hezekiah Moscow, an aspiring boxer from Jamaica trying to survive in the dingy underworld of 1880s London, is many things – brutal, thrilling, fresh – but it is not a barrel of laughs.

The Disney+ show is back for a second season after the first was met last year with critical acclaim and fanfare – a lot of it unexpected. It’s lucky, then, that Kirby is no longer the man who once said he shies away from big roles to better protect his privacy. “I’m in a space of taking big swings,” he says now. So what’s changed? “Me, I guess. Accepting that this is actually what I want to do, so why wouldn’t I make the most of it? And if fame comes with that, if being in the spotlight comes with that, then that’s OK.”

For Kirby, A Thousand Blows arrived like a wish come true – or a prayer answered; the actor is a devout Christian. “I had a conversation with my agent six months before I got the audition, and I said I’d love to play a boxer, and I’d love to do a period drama, and I’d love to do something set in London,” he says. “I just didn’t think it was going to come in one beautiful package.”

Beautiful and bloody. As Hezekiah, Kirby punches and gets punched a lot. Grieving the death of his friend, he’s ekeing out a sombre living amid the grime and grit of Victorian London’s underground boxing scene. All the while in his periphery is Sugar, Hezekiah’s rival played by Stephen Graham, who is hiding away and drinking himself to oblivion, a lion licking his wounds.

A Thousand Blows is a reunion for Kirby and Graham, the two having starred together in 2021’s pressure cooker of a kitchen drama Boiling Point. Is it daunting to act opposite Graham, a heavyweight veteran surfing a new crest in his career thanks to the phenomenon of Adolescence? “No, and that’s probably a testament to him,” says Kirby. “There’s no airs about him. He’s just so... for want of a better word, human.”

There is something beyond the human about Kirby, which isn’t to say he has any airs of his own – only that there is a princely quality in his perfect posture and that steely focus. It makes sense that prior to acting he was pursuing a career in athletics as a 400m track star. (Before that, as a child growing up on an estate in Battersea, Kirby dreamed of being a bus driver.) But there is softness, too; his handshake is more the suggestion of one than the real thing.

He carries that duality into his performance as Hezekiah, a man who remains dignified in the face of abhorrent racism both in the ring and out of it. Having abuse hurled at you can’t be easy, I suggest, even if it is for the cameras. “To be honest, I feel like my career has been made up of scenes like that, scenes of hardship and trauma. Most of the characters I’ve played have been traumatised. Weirdly...” he laughs. “I think that is my comfort zone.”

It’s true that you can’t look at his CV without feeling sympathy for his carriage of characters. There was the young, emotionally shut-off inmate in 2012’s gritty prison thriller Offender, and then the trembling soldier with PTSD in Black Mirror. The 2020 release of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe, in which Kirby played Darcus Howe, an activist put on trial in 1971 on trumped-up charges of inciting a riot in west London, dovetailed powerfully but depressingly with the Black Lives Matter movement in the US and the UK. He earned a Bafta nod for his performance.

If all that sounds like pretty hard going for Kirby, to hear him tell it, the “hard” is what makes something great. “It’s always going to be a challenge, but that’s part of what makes it drama in the first place. I think if it wasn’t challenging, I’d probably be doing something wrong.”

What is tough, he says, is not the expression of pain in a scene but the repetition of it. “The hard part is doing it over and over again while still keeping it grounded in truth. You can’t just try to recreate something because that take felt right,” he says. “Remembering to go on that journey afresh with every take is probably the biggest challenge; when you’ve got all the lights and cameras reminding you that this isn’t real, it’s about holding on to something that is.”

Roots is a prime example of this. Kirby famously portrayed Kunta Kinte in the 2016 remake of the watershed series, itself an adaptation of the Pulitzer-winning 1976 novel by Alex Haley. The story of an 18th-century Gambian man captured and sold to a Virginia plantation owner, Roots asked a lot of its actor. Over five and a half months of filming, Kirby was shackled, assaulted, beaten, and mutilated – all culminating in a scene during which Kinte is tied to a post and flogged in front of his fellow slaves, his real name torturously beaten out of him.

There was no script to follow for the scene – no dictated number of lashes after which Kirby would succumb to the beatings, shout out his character’s new name, and effectively call cut. Instead, what unfolded was an “out-of-body experience” that Kirby can recall vividly even 10 years on. “Being in that space, something happened,” he says. “Being on that soil – because we were shooting on a real plantation – I guess it felt like I was experiencing everything everyone else had ever gone through there, and it was really overwhelming, to say the least. It was something that I didn’t prepare for, and wouldn’t have known how to prepare for.”

When you’ve got all the lights and cameras reminding you that this isn’t real, it’s about holding on to something that is

While he can recall what he felt precisely, the actual details are a blur. “I just remember what happened afterwards,” Kirby says. “Forest [Whitaker, his co-star] came up to me and held me. The cameras were off at this point, but I was shaking. And the producers told me in a really gentle voice that, you know, we can wait to shoot it again tomorrow, but the idea of coming back to it again the next day was awful. So I just got it done then – one more take and then that was that. It was a profound experience for sure, and probably one that will always stay with me.”

If not emotionally, then certainly practically. The role made a breakout star of Kirby, whose career began in earnest thanks to that immense performance as Kinte – a cut more defiant than LeVar Burton’s take on the character back in 1977, but drenched in the same rage and despair. His portrayal was acclaimed across the board. A year later, though, Samuel L Jackson spoke out about the casting of Black British actors in dramas about American race relations; he called out Daniel Kaluuya in Get Out, and David Oyelowo, who had played Martin Luther King in Selma.

Kirby thinks on these examples for a moment, and sidesteps elegantly. “I don’t have anything to say to that specific comment, but I guess my understanding of being an actor and being an artist is telling other people’s stories,” he says. “And also [in this example] Kunta Kinte was African, and I know that Roots is primarily an African-American story but that particular character was African, so I don’t think there’s any difference in me playing him as someone from the diaspora as it would be for an American actor, because we still have to go back to that same beginning.”

Hearing Kirby recount his experience on the set of Roots, it sounds like exactly the sort of thing drama therapists were made for. But while having a psychological helping hand on set is becoming more commonplace in the industry, Kirby hasn’t yet had the chance to partake. “I’ve never done it, but I’m a big advocate of therapy,” he says. “No one really teaches you in drama school how to take care of yourself, what to do when you finish the job so you’re not taking these characters home with you. I can’t imagine how different a person I might be, or maybe [how different] my work would be, if I’d had those spaces specifically.”

Of course, he says, he can speak to his family and friends, and he does to an extent – “but it’s not necessarily a conversation I can have with them from a place of understanding, because they haven’t seen what I’ve been through. For them, they think, well you’re just pretending. But for me, acting is a pursuit of the truth, and I take that really seriously. It’s not pretend.”

Kirby wasn’t always so serious about acting; in fact, it was his mother who had to convince him that it was a good idea to give it a go. “I owe it to her, and also to my dad, who saw something in me when I was younger,” he says. Kirby’s father, a mechanic and welder, died when he was six years old. And so, with his mother’s encouragement, he enrolled in the Identity School of Acting in London, where his classmates included Letitia Wright, Damson Idris, and John Boyega. Michaela Coel was in the year above. “I attribute so much of my success to the people that I was in the room with,” he says. “I’ve spoken to other people who have gone to drama school and had different experiences, but for me, it was a really, really safe space.”

Coming out of training, Kirby landed acting jobs on the UK telly circuit: Casualty; Silent Witness; an eight-episode run playing Danny Dyer’s son-in-law on EastEnders. He was shortlisted for the Outstanding Newcomer Evening Standard award in 2011 for his performance in the play Mogadishu, and then flew to Zanzibar to shoot a short film with his friend Kaluuya. Unlike Kaluuya – who broke through on Skins but found international fame in Jordan Peele’s Oscar-winning horror Get Out, and who has spoken about the dearth of roles for Black actors in the UK – Kirby did not feel the need to decamp to the US.

“People often say to me, ‘Oh, what are you doing here? I thought you’d move to the US,’ but I’ve only done one job out there,” he says. “Actually, it wasn’t a thing that I felt was necessary in order to have a career.” That said, he would like to do more work across the ocean. “I’ve had a rep out there for 10 years, and they’re very underused.”

Also “very underused” are Kirby’s comedic chops, which he assures me he has in spades. “I like smiling and I’d like to do some comedy,” he says. “Some of the actors I aspired to, the ones I loved the most, were Eddie Murphy and Robin Williams... Jim Carrey – really wacky stuff.” It’s hard to imagine Kirby, stoic and monastic, gurning like Ace Ventura or strapping on a fake bosom to cosplay an English nanny. But who knows? “You may see a different side to me,” Kirby says, knowingly.

Seasons one and two of ‘A Thousand Blows’ are on Disney+ now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks