Jonathan Pryce: ‘Does Ricky Gervais watch his own work? He shouldn’t’

The Welsh acting great talks to Patrick Smith about ‘Game of Thrones’, seeing his father’s ghost, the vanity of youth, and his new crime drama ‘Under Salt Marsh’, shot near his boyhood haunts

Jonathan Pryce slept through his own death. Not his real one, evidently, but that of the High Sparrow, his malevolent zealot in HBO’s sex-and-swords smash Game of Thrones, who was incinerated in a spectacular sequence that used CGI to ape medieval pyrotechnics. When it aired on TV, “there was this really slow build-up to it. It went on for ever,” the star of Brazil and The Crown recalls, “... and I fell asleep.”

The following morning, he met his son Gabriel for breakfast at a café. The waiter took their order. “Don’t worry,” the young man joked, “it won’t be green.”

Pryce looked up at him, mystified, and chuckled politely. “Gabe said to me, ‘You don’t know what he’s talking about, do you, Dad? That’s how you died.’” The green in question – as any Thrones fan will tell you – is wildfire, the magical, highly volatile liquid deployed by Cersei Lannister to torch her enemies confined within the Great Sept of Baelor. “So I made a point of watching it again that night,” says Pryce.

He hasn’t seen the heavily divisive finale of Game of Thrones, either – the one that ripped up the narrative arc of the previous 72 episodes and left millions nursing a sense of personal grievance. A lot of actors don’t watch their own films or shows, I say. “Well, when you see the work, you know why,” he returns. “Does Ricky Gervais watch his own work? I bet he does.” He laughs; the zinger is coming. “He shouldn’t.”

We’re in a hotel room in central London, a few hours before Pryce is due at a screening of Under Salt Marsh, a gripping new crime series that launched on Sky on Friday. Claire Oakley’s six-parter is about a fractured Welsh community forced to confront buried secrets when a young boy is found drowned just outside the remote coastal town of Morfa Halen, reopening a three-year-old cold case. Two hundred people will be watching at Bafta HQ. It’ll be the first time Pryce has seen it, too. Obviously.

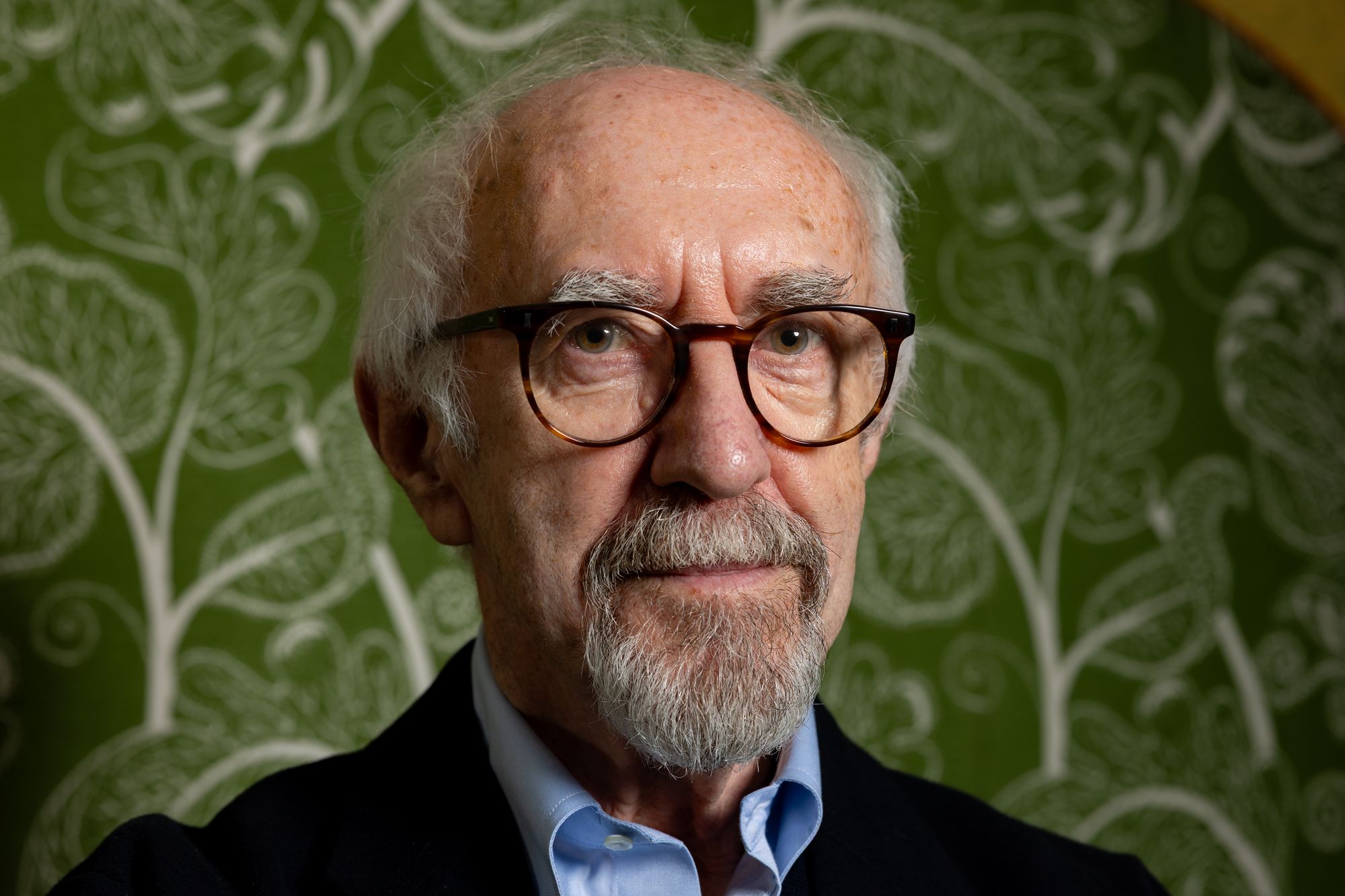

Game of Thrones? It’s a genre that doesn’t interest me

At 78, the actor cuts an unshowy figure – silver goatee, high-domed forehead, blazer worn over a slightly rumpled sweater, and expressive eyes that can shift from sardonic to warm in the space of a sentence. If he was once more cautious in interviews, coming across as a little saturnine, he’s looser now, illuminated by flashes of wry humour. His voice is textured and melodious; he has an avuncular air, asking about my name and Irish roots (he has a son called Patrick, one of three children with his wife of 43 years, the Irish actress Kate Fahy). When I mention having a headache, he fishes two loose orange pills from his pocket. “Nurofen,” he announces. “Well, I hope they’re Nurofen.”

There’s none of this playfulness in Solomon, his character in Under Salt Marsh. The script describes the town’s retired minister as “a tall, powerful figure”, but in Pryce’s hands, he’s sombre and contained – until Rafe Spall’s detective gets under his skin and a volcanic rage erupts from within. “I enjoyed that scene,” Pryce says, his eyes crinkling slightly. “It’s generally quite nice to get to shout at people.”

While there’s not exactly a dearth of new British crime drama serials, Oakley’s series has a sepulchral atmosphere that sets it apart, with Yellowstone star Kelly Reilly terrific as detective-turned-teacher Jackie Ellis. There is more than a whiff, too, of Scandi-noir whodunit The Killing, as the ensuing investigation unites police dysfunction, small-town suspicion, and climate-crisis-abetted natural disaster.

For Pryce, the series marks a homecoming of sorts. It was shot across Anglesey and along the North Wales coast, down to Barmouth – territory Pryce knew intimately from his adolescence, though he grew up further east in Holywell, on the banks of the River Dee. “You could see Liverpool in the distance,” he notes. As a teenager, he cavorted with what he describes, with careful understatement, as a gang. “The majority of them were older than me, so they all had motorbikes, and I was the pillion rider.” They’d head out to pubs along the coastline “ostensibly to drink, but really we were looking out for Welsh girls”.

Leaving Wales at 18 for Edge Hill college in Lancashire, then Rada at 21, Pryce has remained tethered. His two sisters still live in Holywell, along with his nephews and nieces, and in recent years he’s become vice-president of the local choir, which allowed him to sing alongside his old geography teacher. Most old schoolmates remain in contact, he says, “because they see me on TV, so there’s that connection”.

Under Salt Marsh is the latest television foray of a man who is widely regarded as one of the great stage actors of his generation, with two Oliviers and two Tonys to his name, including one of each for his originating role as The Engineer in Miss Saigon.

On screen, over five decades, he has walked the line between movie star and character actor, often cast in parts that imbue him with authority: celebrated writers (1995’s Carrington, for which he won Best Actor at Cannes), religious leaders (1998’s Stigmata), IRA bosses (1998’s Ronin). There’s a watchfulness to how he performs – whether as a cardinal or a spy, a Bond villain or a Shakespearean lead – that makes him compelling even in stillness; a facility for hinting at entire interior worlds with just the smallest shift in his expression.

By the time he’d reached 60, he’d already accumulated an impressive body of work – from Brazil (1985) and Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) to Evita (1996) and the first three Pirates of the Caribbean movies (2003-2007). I mention 60 for a reason. He’d told an interviewer that he’d retire by then. “I was probably about 40 when I said it,” he admits now. So what changed? “Well, there are few others in my age range, so there’s more parts for fewer people. I just still enjoy it. If I didn’t enjoy it, and if I wasn’t doing work at the level of Slow Horses or The Crown [in which he played Prince Philip], it would be very different.”

Slow Horses, the Apple TV+ espionage thriller, has transformed Pryce into something of a cult hero among a discerning subset of viewers. Its shabby world of failed spies crackles with wit, showcasing performances that are calibrated to perfection. “The good thing about it, and [the writer] Mick Herron will tell you this, is that it’s character-driven and not plot-driven,” he explains.

He plays David Cartwright, former head of MI5, whose grandson is Jack Lowden’s to-the-manor-born spy River Cartwright. Crucially, Pryce hadn’t read Herron’s novels before filming began. “I didn’t know [David] Cartwright’s story, so in the first series, there wasn’t an indication. And I’m glad that I didn’t know.” The character’s gradual cognitive decline revealed itself to Pryce at “the same time as the audience learnt about it”, he says.

The dementia element reverberated beyond the show. For Pryce, the ripples began when he appeared on stage in Florian Zeller’s The Height of the Storm; people would congregate at the stage door afterwards, wanting to share their own experiences.

“That was the first time I had an awareness of the power of drama, getting a message across,” he says. “Most of them were people who would say it was the first time they’d felt it was a problem that was shared, the first time they’d been able to cry since their relative had died. Some– a few men especially – had given up their job to go and look after their parents.” When I mention that my partner’s father has dementia, he nods. “The comfort [for carers] is that [their loved ones] aren’t in distress and anxious themselves,” he says. “That distress is never going to go away from a carer. That’s the worst thing about it.”

Cartwright joins a growing list of memorable late-career performances for Pryce. Witness his scene-stealing portrayal of Cardinal Wolsey in Wolf Hall (2015), or his pampered turn opposite Glenn Close in The Wife (2017) as a novelist whose spouse has all the talent. This renaissance peaked with his Oscar nomination for The Two Popes (2019). “It was absolutely brilliant,” he says of the experience. “Working with Tony Hopkins was so enjoyable, great director, great producers.”

Game of Thrones reminded audiences how good an actor Pryce is, but he originally turned down the pilot. “It’s a genre that – [I was] going to say didn’t interest me; it still doesn’t interest me,” he admits. “I started to look at [the script], all these weird names, and I was flipping through, and I was like, ‘Not for me.’” Then, of course, it became the biggest television phenomenon in history. “So I waited until it was a hit. Season five, I think it was.”

Pryce based the High Sparrow on someone entirely unexpected: Pope Francis, who’d only recently been installed in the Vatican – and whom, ironically, he would later portray in The Two Popes. “He was doing all the things the High Sparrow was doing – washing the feet of the poor, feeding them. And I played [the High Sparrow] as quite a noble character.” Then he received the scripts for series six. “And I was like, he does what? He’d turned into a complete homophobic, racist, horrible monster. But if I’d known that, I wouldn’t have played him as a good guy, which is what he presented to the world.”

For decades, Pryce had enjoyed the luxury of moving through the world largely unrecognised. But then, touring China with The Merchant of Venice, he took a boat to a small fishing island off Hong Kong. “I’m coming down the gangplank, and all the locals are pointing at me, going, ‘Hi Sparrow! Hi Sparrow!’” He laughs. “They’re obviously watching it illegally, because there’s no way you can watch it in Hong Kong or China. That was weird.”

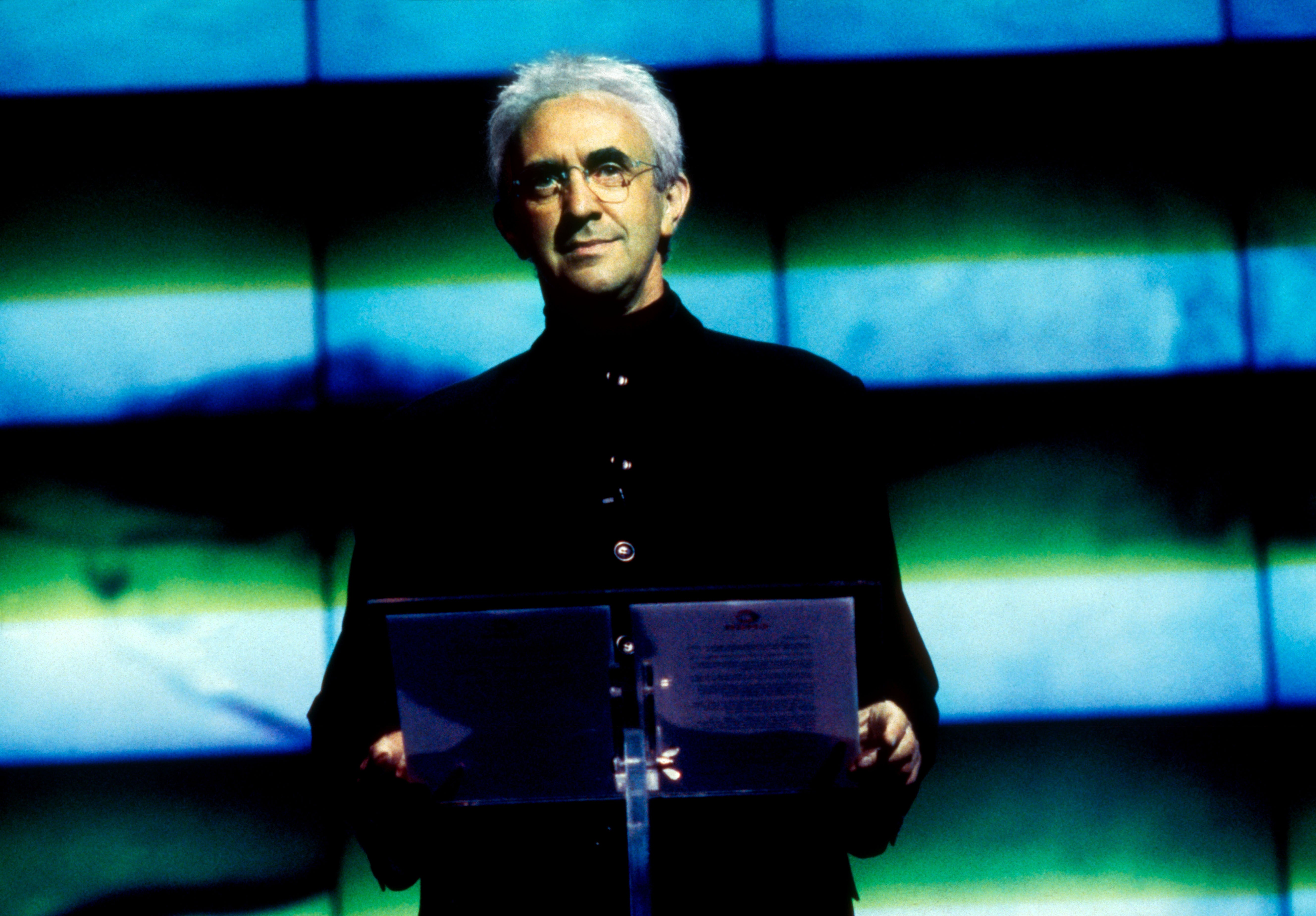

It wasn’t his first encounter with big-budget franchises, though. In 1997’s Tomorrow Never Dies, Pierce Brosnan’s second outing as 007, Pryce played media mogul Elliot Carver, who wanted to kickstart a world war to secure broadcasting rights in China. The promotional circus was peak Bond – private jet to Paris, BMWs waiting on the tarmac, no passport control, straight to the most expensive hotel. He sat there “feeling very grumpy” about the carbon footprint. The film itself was a “fantastic” experience, he says, though he was resigned to his character’s fate. “The classic Bond villain moment where I could have killed him, I had my gun on him, for some reason I didn’t. Instead, he killed me, and I’m churned up in this machine thing.”

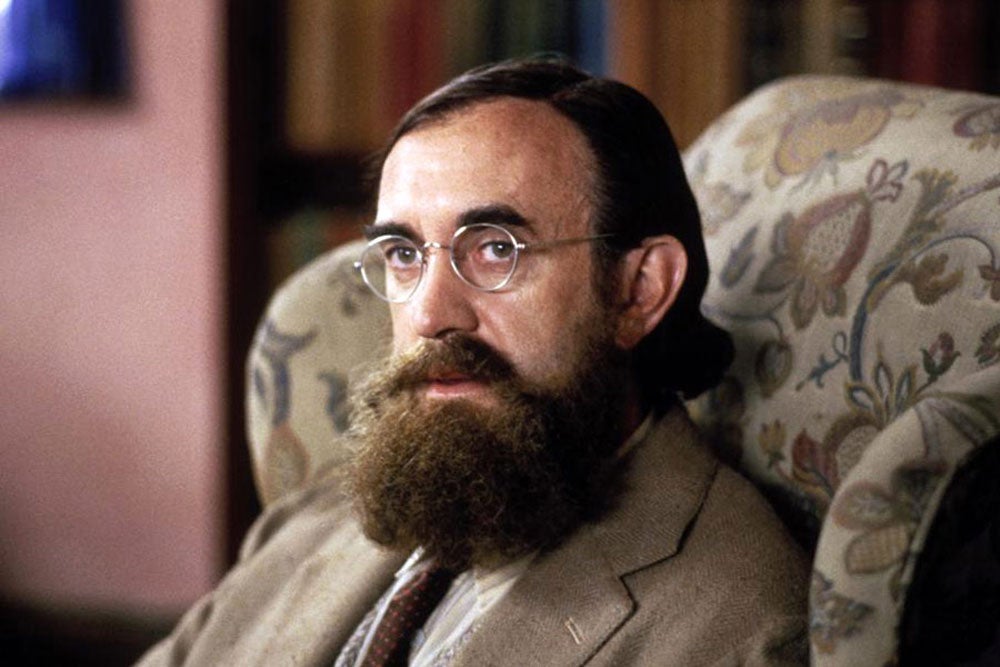

But there’s one performance that Pryce has never stopped thinking about, one in which the breach between real life and make-believe collapsed entirely: his Hamlet in 1980, directed by Richard Eyre at the Royal Court. Pryce’s father, a former coal miner, was violently attacked with a hammer while running a grocer’s shop in north Wales; when he died two years later from his injuries, Pryce was performing in New York, and was unable to return home for the funeral. So when Eyre talked him into taking on Hamlet, he began thinking about his dad.

“Hamlet – his father died as a result of violence,” he says, “and Hamlet felt guilty because he hadn’t avenged his death, and he had suspicions of his uncle that he’d killed him. And I felt some guilt, I think, that I hadn’t done anything about it, or felt anger.” Then something else happened. “I thought I’d seen my father appear to me. I just saw him standing in the garden and looking at me.” Pryce understood what Hamlet was going through – the way grief manifests what you most need to see. “I thought he’d conjured up the ghost, knew what his father would have said. And I thought I’d conjured up my father because I so wanted to see him.”

On stage, Pryce’s Hamlet would speak the lines of his father’s ghost, effectively pleading with himself to avenge his own death. He dredged the voice up from within. “I was doing the equivalent of belly speaking. I’d watched videos of women in voodoo trances and talking in tongues.” Some nights, the audience would respond with nervous laughter. “I could hear them tittering a bit. Then you could almost feel them go, ‘F***ing hell.’ Suddenly it has the effect that you want it to have.”

Just as Hamlet emphatically marked Pryce’s arrival on the stage, so Brazil secured his place in cinematic lore. He still does Q&As for screenings around the world, travelling to discuss Terry Gilliam’s dystopian masterpiece with audiences who discovered it decades after its release. “People talk about how it changed their lives,” he says. “A lot of filmmakers say it was the most influential thing on their career. I think that’s how I’m still picking up work.”

These days, he finds seeing himself on screen has become less fraught. “When you’re younger, I’d watch things differently and I didn’t enjoy the experience. And a lot of it’s to do with vanity, I think. You think, did I really look like that? And the older you get, it’s too late. That side of it doesn’t matter.” But something else has emerged. “I’ve got some kind of dysmorphia, I think,” he says. “When I look in the mirror, I don’t see an old person. Except when I go out on the street and I happen to glance in a shop window, and it’s like, who is that old man walking alongside me?”

Our conversation wraps up. As I stand to leave, he asks if the Nurofen worked. It did. “Good,” he says with a laugh. “And your pupils look fine.”

‘Under Salt Marsh’ airs on Fridays on Sky and the streaming service NOW

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks