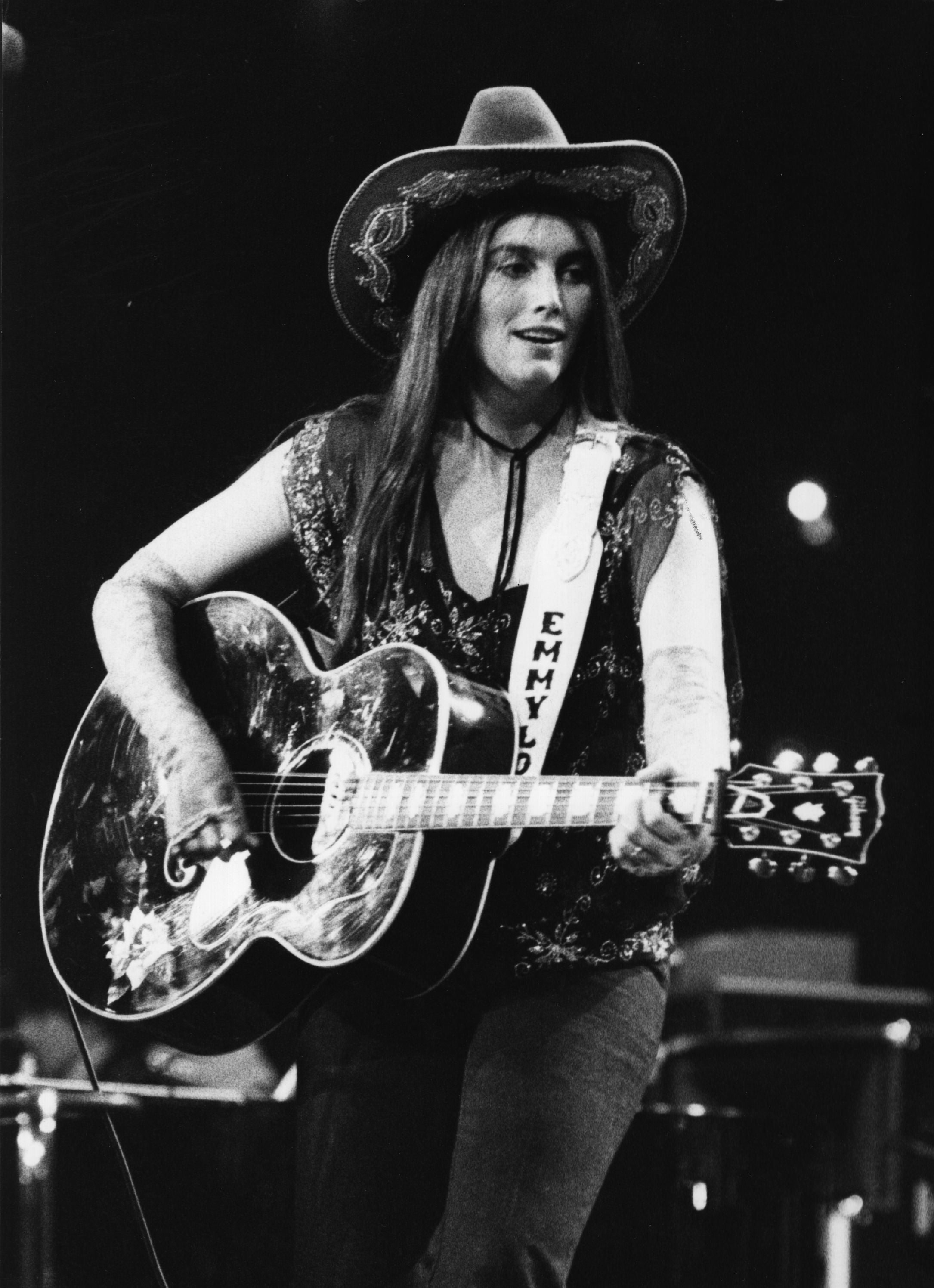

Emmylou Harris: ‘It’s a lot harder, isn’t it, to just live a long life?’

As the country music titan prepares for her final European performances, she speaks to Louis Chilton about life, mortality, and being part of the ‘greatest era’ of music

For a moment, I’m worried I’ve offended one of our greatest living country artists. Emmylou Harris has hung up on me, less than a minute into our call. A moment later, though, she’s back, apologising. No offence caused (phew), just a snafu with her computer. “I get a little freaked out by technology,” she admits.

It’s hard to believe Harris could be fazed by anything. Just look at her career: a beacon of the country music scene in the 1970s and 1980s, she ultimately proved too adventurous for the tradition-fixated genre, leading it towards new and innovative frontiers... whether it followed or not. “I haven’t fit into country since I turned 40,” she tells me. “I was too old, apparently, for country radio, and they stopped playing me completely.” Fortunately, she points out, “I never had to live and die by the charts.”

We’re speaking midway through Harris’s farewell to her European touring career, which concludes with a run of dates this May. There’s no new material on the horizon, either: “I’ve decided I have enough records, and enough material to last me however long I’m going to be doing it,” she says. But she’ll keep performing live, only within the borders of her native US. “It’s a little bittersweet,” she says. “My first loyal audience started coming from over your way. Gram Parsons [Harris’s early musical partner] had a bigger profile overseas, and I was able to latch onto that. Audiences over there seem to be better informed.” Though it is, she adds, “better in the States” than it used to be.

Now 78, Harris talks in a sort of earthy half-staccato; a cold-caller might be hard-pressed to match the speaker to the sweet soulfulness of her music. Listening to her singing voice – graceful and crystalline, especially on her early records – can feel like a religious experience. Sometimes this is literally the case, as on the 1979 Christmas album Light of the Stable, her seraphic soprano matched perfectly to earnest Christian material. Elsewhere, her voice finds God in the everyday, in the sublime sadness of ballads such as “Wrecking Ball” or “Prayer in Open D”.

Even more remarkable is just how elegantly Harris’s voice seems to synergise: many of her best songs are duets, and the range of singing partners, from Parsons, to Willie Nelson, to Don Williams, showcases just how versatile an instrument it is. “I don’t really know what I’m doing, frankly,” she says. “I’m not a schooled musician, or a schooled singer, so I’m just looking for something that creates an interesting sound, and [that’s right for] the emotional story you’re trying to tell.”

Harris’s father was a Marine Corps officer and a POW in Vietnam; his job took the family from Birmingham, Alabama, to Woodbridge, Virginia. Harris first aspired to be an actor, studying drama at the University of North Carolina. By the time she got to “more serious” acting school, she was already feeling the pull of music. “When I got into acting classes, I discovered that it was a completely different feeling,” she says. “When I was singing, I felt that I was in a zone of some kind. And I was never able to capture that same feeling as an actor.”

It was the burgeoning, politically charged folk scene that first grabbed her; this was the Sixties, after all, when artists like Joan Baez and Bob Dylan were in their ascendancy. In the late 1960s, Harris moved to New York’s Greenwich Village to be near them, instead meeting and promptly marrying her first husband, folk singer Tom Slocum – a union that within two years resulted in the birth of her first child, Hallie, and a divorce. “We didn’t have a long marriage, but we had a marriage that worked for a while,” she says fondly. She remains close, more so, with her other two ex-husbands: “I just think you’re grateful for the good times.”

After dabbling in folk – her debut album, Gliding Bird (1970), failed to make much of an impression – Harris gradually transitioned to country music. She first approached the genre with a sort of “tongue-in-cheek” attitude – explaining in the documentary From a Deeper Well that she was put off by the genre’s associations with “right-wing stuff”. Now, though, she reckons that country music is just something you have to grow into. “I was really young, and I hadn’t really faced the adult problems of, you know, paying the rent,” she says. “But country music really deals with grown-up issues, doesn’t it? Getting your heart broken – and death. Our own mortality. Grown-up issues that we all eventually face.”

Harris brings up mortality a few times during our interview; it’s something that’s clearly on her mind. But of course, it’s also something that has confronted her throughout her life, sometimes in painful and unexpected ways. In the early Seventies, after Harris left Greenwich Village and moved back in with her parents, by then living in Washington DC, it was Parsons who recognised her immense talent and brought her out to LA in 1972. She toured with his band, and this evolved into a rich musical partnership. During the recording of the album Grievous Angel, the former Byrds singer died of a drug and alcohol overdose, at the age of 26. It was a grief that Harris would reckon with, personally and musically, for years after.

“You know that romanticised thing... There’s a song called, ‘I want to live fast, love hard, die young, and leave a beautiful memory’,” Harris says, referring to the 1955 hit by country singer Faron Young. “It’s a lot harder, isn’t it, to just live a long life? I don’t see anything really romantic in the fact that Gram died so young. It’s just a tragedy. But that was the fact of it. And so each of us carries on in our own way.”

Parsons inspired her songwriting, including on the earth-shaking “Boulder to Birmingham”. But, she says, “I don’t know if anyone really understands the process of grieving. I suppose when you’re dealing with a feeling, writing a song kind of builds a fence around it. And it does help you move on somehow.”

I don't see anything really romantic in the fact that Gram died so young. It’s just a tragedy

After Parsons’s death, Harris emerged as a major force in her own right, recording a string of successful albums throughout the 1970s. Her popularity dipped in the following decade, before the supergroup Trio collaboration with Linda Ronstadt and Dolly Parton brought her back into the mainstream consciousness. Whatever her circumstances, though, she was consistently able to make the music she wanted to make, whether that was pure, throwback bluegrass or the pop-inflected Stumble into Grace. “I don’t think I’ve ever had to fight that much as an artist,” she says. “I guess I’m an independent person, but I found myself in circumstances that made that possible. [My record label] Warner Bros respected me as an artist, and I’ve had a lot of artistic freedom throughout my entire career.”

These days, Harris confesses she isn’t really tapped into what’s going on in music: “It seems like I mainly listen to my old pals,” she says, breaking into a warm, endearing laugh. “People like Leonard Cohen, my folk heroes, and all the people that influenced and encouraged me, some of them I worked with. And that’s what inspires me still, what moves me still.”

I mention that this year marks the 50th anniversary of The Last Waltz, Martin Scorsese’s classic concert film capturing the star-studded farewell performance by The Band. The song “Evangeline”, a wonderful, timeless country-rock number, was recorded by Harris on a soundstage, months after the gig itself. “The Last Waltz made me realise that I didn’t want to be an actress,” she says. “It took so long... I think we recorded for three days, staying in a little trailer, just to get that one song. I didn’t have that kind of stamina, I think. But I’m still very grateful to have been a part of that extraordinary project.”

When you look at the other guests in The Last Waltz – among them Dylan, Neil Young, Dr John, Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell, Eric Clapton, and Muddy Waters – it’s hard to shake the sense that this was a special, unreplicable moment in music history, a generation of talent that makes today’s artists seem somewhat drab in comparison. “I think it’s kind of arrogant, on both our parts, to consider that,” counters Harris. Even so... “I can’t help but think that I came up in the greatest era, of the greatest music, that is going to stand the test of time.”

As for what comes next, “We’ll just have to wait and see,” she says cheerily. “But I certainly won’t be around to see it.”

Emmylou Harris’s European tour continues from 11 to 24 May, including a performance at the Royal Albert Hall’s Highways Festival on 17 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks