Brendan Gleeson: ‘I was always more interested in enjoying life than being pretty’

The Oscar-nominated star of ‘The Banshees of Inisherin’ talks to Patrick Smith about ‘H Is for Hawk’, the Irish attitude to death, toxic scripts, the dangers of overenthusiastic parenting, and actors losing their looks

Brendan Gleeson can’t stop talking. Materialising on my laptop screen, the Oscar-nominated star of The Banshees of Inisherin and Harry Potter sails through twinkly-eyed anecdotes and impassioned detours about parenting, the Northern Ireland peace process, and toxic masculinity. He apologises for “going on a bit”, then immediately goes on a bit more. It’s great.

Far from the grouchy or mean men he's often inhabited, Gleeson is gentle and gregarious. We’re discussing H is for Hawk, Philippa Lowthorpe’s sensitive adaptation of Helen Macdonald’s bestselling memoir, in which Gleeson’s patriarch dies early but hovers over every frame. It’s led us on to the difference between the Irish approach to death and that of the English. This takes the Dubliner back to the funeral of a friend – Anthony Minghella, who directed Gleeson in Cold Mountain five years before he died in 2008.

“At an Irish funeral, if the man or the woman has had a life, all you hear is people laughing and telling stories,” Gleeson explains, his Gaelic burr mild yet brooking no interruption. “It's all about what a life they’ve had, how they embraced the life.”

But that really wasn’t the vibe when the director of The English Patient was laid to rest, Gleeson says. “I remember going to his funeral and being absolutely stunned by the lack of…” He trails off, recalibrates. “I’d be telling funny stories about Anthony, about things on set, and how, you know, he said he’d do Beckett with me and I’m still waiting.”

Instead, the 70-year-old continues, “it was all dignity. It was all ceremony. It was all very beautiful in its own way, and full of emotion.” In Ireland, by contrast, “there is always conversation, and far more immediate engagement with the person that was there, and you can feel them there, like even in the wake. It’s an incredible, communal embrace of death, in a way that doesn’t happen in Britain.”

In H is for Hawk, Claire Foy’s Helen faces her father’s death by training a goshawk called Mabel. The story is set in Cambridge and the Brecklands on the Norfolk-Suffolk border, and the dad in question is the celebrated real-life photojournalist Alisdair Macdonald. A frequent chronicler of The Beatles’ live shows, he was also responsible for the famous shot of Princess Diana and Prince Charles kissing on the balcony of Buckingham Palace.

What drew Gleeson to the role was the chance to play a good man. “I had become very tired of the trope of the toxic father becoming absolutely relentless in the scripts I was reading,” he says. “And I got very bored with it first, and then I got very sort of irritated by it, and then I began to feel that there was a dearth of role models for young men with regard to fatherhood, being perpetuated in script after script after script.” Young men are already insecure about society’s expectations, he argues. “So I thought the opportunity to play a good father was incredibly valuable.”

It’s Alisdair who encourages Helen’s love of nature, introducing her to birding on their expeditions together. After his death, she becomes consumed by her devotion to Mabel – who is not just any bird, but a predator with a froideur yet to thaw. Keeping Mabel on her wrist at all times, even as a don at Cambridge, Helen cuts an eccentric figure as her life unravels and her house falls into squalor.

Foy underwent extensive training to handle the birds, and her scenes carry real authenticity – it’s clear that she’s taking it seriously, juggling what one reviewer called “an Apache gunship-like killing machine strapped to her arm” with a wonderfully raw performance. “She’s unbelievable,” Gleeson says. “She has such depth; you can feel a kind of huge intensity in terms of what she’s experiencing.”

Just as Foy commits fully to the physical demands, so Gleeson imbues his scenes with a dignity that keeps any mawkish sentiment at arm’s length. He made a deliberate choice to play Alisdair with a Scottish accent, rather than the London one the real Macdonald would have had. “I don’t look like him anyway,” he says. “So I kind of went from the basis that I cannot do this person as he was in life, visually. So it would have to be a kind of poetic licence.” He found he could express himself more naturally in a Scottish lilt. “We’re kind of cousins,” he explains, referring to the Scots and the Irish. “There’s more reticence in the way that Londoners emotionally engage.” Helen Macdonald gave her blessing; she said her father would have liked it.

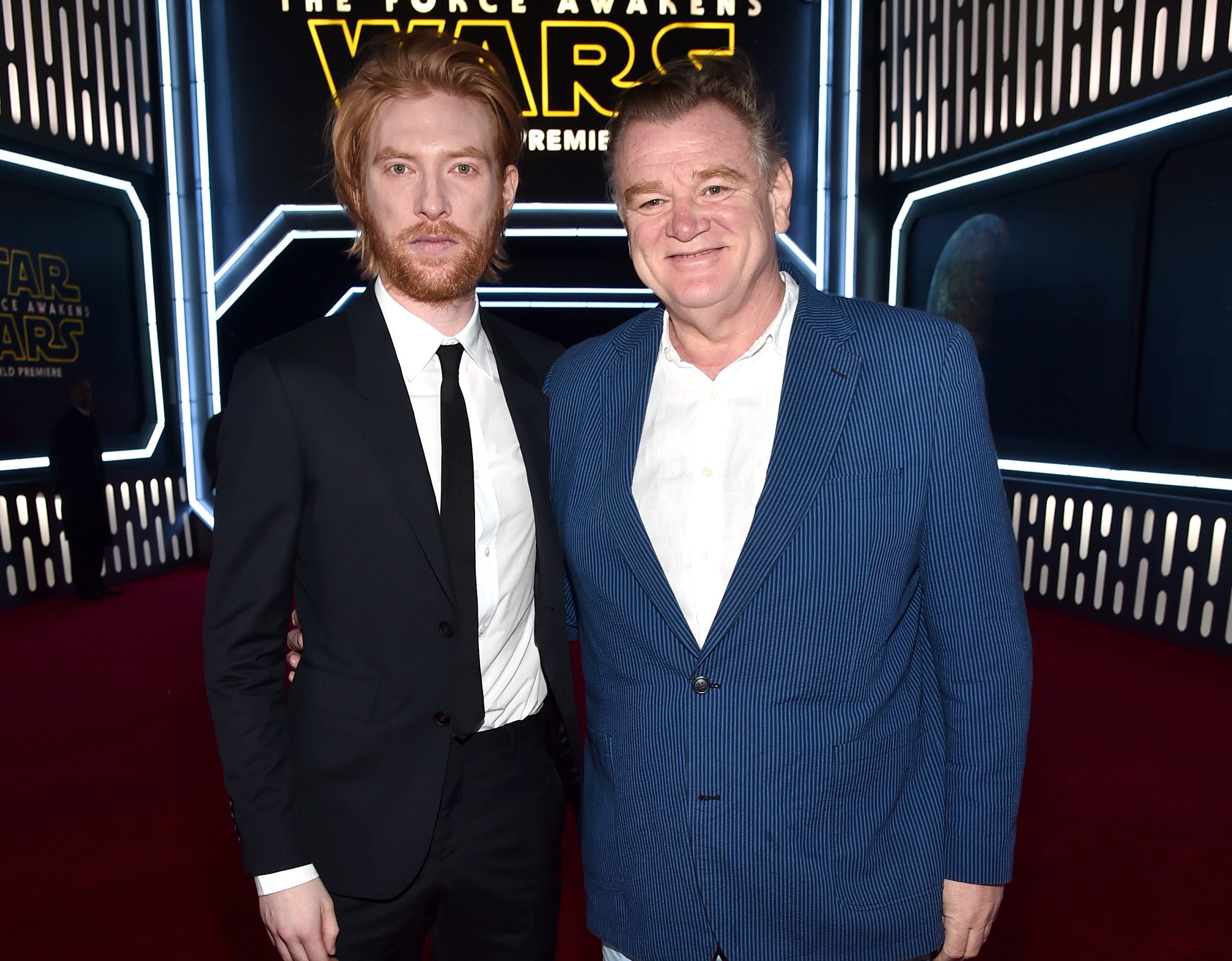

By any measure, training a goshawk is an unusual response to death, but it springs, at least in part, from how Helen was given permission by her father to be strange. This resonates with Gleeson, though he’s careful about where that permission ends. His own four sons with wife Mary Weldon – Domhnall, who’s carved out his own stellar career in Ex Machina and Star Wars, and Brian (Peaky Blinders) are actors, while Fergus works in film production and Rory is a writer – were raised with a similar freedom, but within limits.

“There’s a line with everything in parenthood,” says Gleeson. “If the strangeness is not going to make them happy, in the sense that there’s excessive aloneness,” he suggests, you have to find ways to help a child integrate with others, “because you don’t want to get completely removed from your environment. We’re kind of herd animals by fundamental instinct.”

His own generation rebelled against conformity and demanded personal expression. “But then if you bust out of it, to where you say it doesn’t matter how you engage with your environment, you raise a lot of brats who think that they’re the only people in the world and that their concerns are the only concerns of the world.” Covid seems to have made it worse, he notes – alienated people, made them afraid to talk, uncertain how to get along with others. “And if you let everybody do everything that they want to do, and it’s all child-centred, and everything has to be that way, they have no way of engaging with the world that makes any sense to anybody else, because they’re all just looking after their own corner.”

You don’t have to be a wellness factory, but we’re better off being kind

Gleeson is wary of the current obsession with telling children they’re brilliant at everything. “The last thing you want to be doing as parents is shoving people into their own corner and saying, ‘You’re unique, and everybody really should sit up and recognise how brilliant you are.’” His generation faced the reverse problem – being told ‘You’re s***’, that they shouldn’t try things. “But now, having to deal with the pendulum swinging over to where people are being given false expectations of what is possible – I don’t think it’s doing them any favours.”

.jpeg)

Gleeson himself came to acting late, only turning professional at 34. Before that, he taught Irish and English at a secondary school in north Dublin, moonlighting with amateur theatre companies including Paul Mercier’s Passion Machine, which staged contemporary Irish stories for working-class audiences. Acting professionally felt out of reach. “I really did think that the professional stage was for other people,” he told The Guardian in 2022. But then he’d watch plays and think he could do better. He could.

For more than three decades, Gleeson has moved freely between arthouse and blockbuster. Reviewing his West End debut in Conor McPherson’s sublime revival of The Weir, The Telegraph said his performance was proof that Gleeson is “one of the greats”. He laughs when I tell him this. “I would be very wary, having had to battle through certain rage with regard to what people were not seeing on stage, to be fully embracing something that is so tremendously uplifting for the ego.” The reviewer was right, though. Gleeson has a rare gift for balancing menace with unexpected tenderness, and his knack for the curmudgeonly – whether played for laughs or for darkness – remains unmatched.

There’s a through-line starting from his breakout role in The General (1998), John Boorman’s portrait of Dublin gangster Martin Cahill, in which Gleeson found both charm and bristling threat in a real-life criminal. It carried through to his career-defining turn opposite Colin Farrell in Martin McDonagh’s In Bruges (2008), as a contract killer grappling with guilt amid the medieval architecture of Belgium. And then his shattering work in Calvary (2014) as Father James, a priest marked for death who spends his final days radiating wounded dignity.

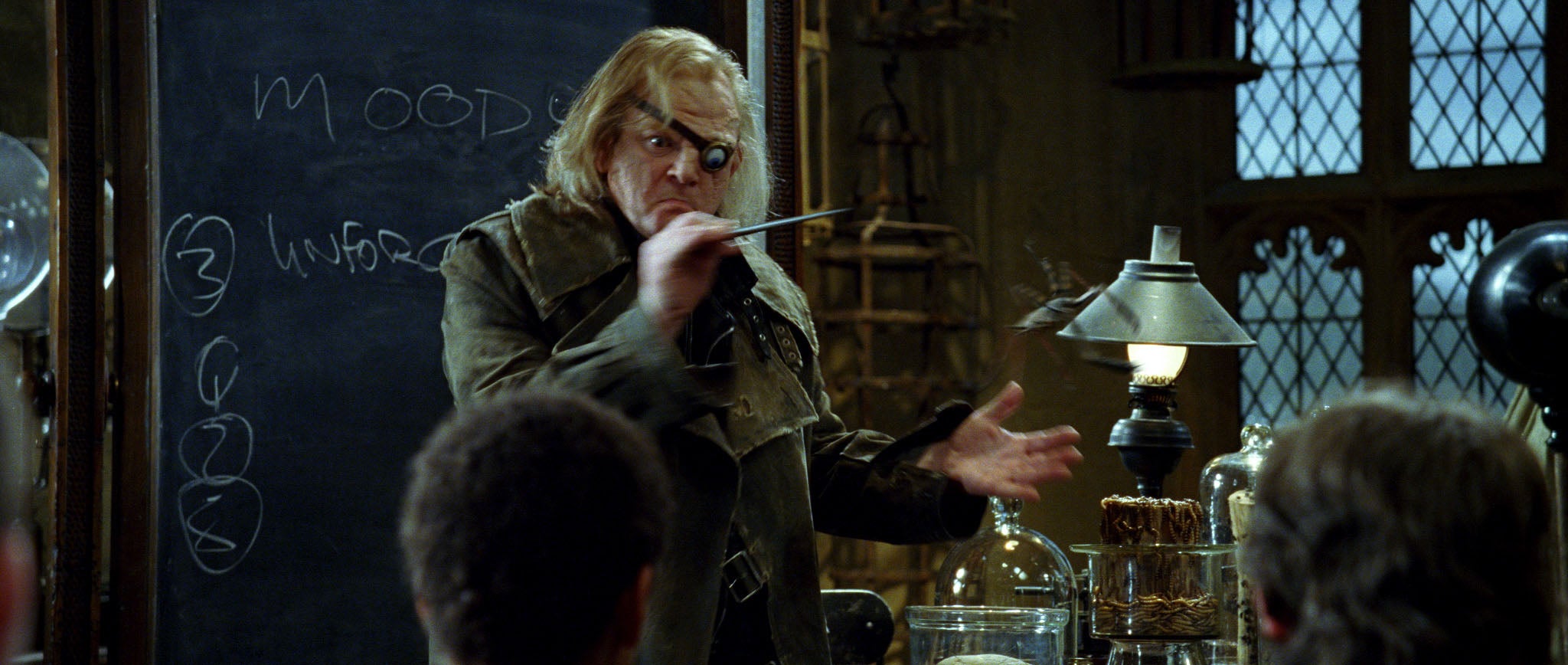

Reunited with Farrell and McDonagh for The Banshees of Inisherin (2022), he earned his first Oscar nomination for his wounded, stoic performance as a fiddler ending a friendship. Then there’s the paranoid, magical Mad-Eye Moody he played across four Harry Potter films, and Knuckles McGinty, the prison bruiser softened by marmalade in Paddington 2 (2017). He’s been Churchill and Trump, hitmen and holy men; he’s worked with the greats – Spielberg (AI: Artificial Intelligence), Scorsese (Gangs of New York), Ridley Scott (Kingdom of Heaven), and the Coen brothers (The Ballad of Buster Scruggs) – and even bellowed defiance at the English in Braveheart (1995).

Ask him about working with the likes of Spielberg and Boorman, and he becomes reverential. “They’re the heroes,” he says. “John Boorman – I did a thing for the Cork Film Festival where they honoured him as a disruptor. I quoted this stone he had in Wicklow with Celtic swirls carved on it by a monk. Underneath, it said: ‘John Boorman caused this to be made.’ And I thought, how many things has John Boorman caused to be made? All the things of beauty that he had been part of.” He pauses. “These guys have been doing this their whole lives, fighting against commerce, fighting to get everything, to try and create something of wonder.”

The same goes for Scorsese. “When I did Gangs of New York, I went to meet him in Rome,” Gleeson remembers. “He gave me this script, and I couldn’t get over it – he said, ‘I’ve been trying to make this for 25 years.’ I said, you’ve chronicled the American experience, and you can’t get the money to make a movie about New York. How is this possible?”

When I mention the Harry Potter films in our discussion about parenting – Daniel Radcliffe was 16, Gleeson 49, when they first appeared together in The Goblet of Fire – and ask what he thought of its young stars coming out against JK Rowling’s hostile views towards trans women, he forcefully demurs. But the flashpoint leads us towards his views more generally on intractable conflicts. “I think this is what we can best do as artists: show people that they’re better off being compassionate, being kinder,” he explains. “And it doesn’t mean that you can’t have a slag about somebody, because you don’t have to turn into sort of a wellness factory. What you have to do is just literally believe in the goodness of people, that people only want a chance to live good lives. I really believe that’s what they want to do. Most people. All across the world.”

He invokes the struggle for peace in Northern Ireland. “We had trouble there for how many years? Both sides were white, both sides were Christian. But one believed in the Communion and water into wine, and one believed that was rubbish. And they managed to divide themselves into two tribes.” The peace process worked, he argues, because it embraced difference. “You could be Irish, British, or both. One passport, two passports – you decide. Parity of esteem. You give parity of esteem to others and their views, and then you make decisions about what laws you enact by trying to be as fair and compassionate as you can to the most people.”

Even on Zoom, Gleeson has real presence. When he laughs – which he does often – his eyes narrow and his grin spreads wide, transforming those craggy features entirely. His face is a palimpsest of everyone he’s played and everything he’s lived.

I bring up the Guardian interview in which he was quoted as saying, “I haven’t got a pretty face”. Does he think that’s been liberating, not having to manage the loss of looks in the way that conventionally handsome actors do? Gleeson laughs. “That’s a really interesting question,” he says. The camera tells a story, he explains, and appearance is part of that story. “If you have a romantic movie, and these two sublime-looking people are looking at each other, the story is almost told in itself.” He’s never been bothered about chiselling his looks or whitening his teeth. “I was always more interested in enjoying life, in a way that allowed me to understand the lives of people who live in the world, as against the people who photograph themselves living in the world.”

Gleeson is fascinated by how good-looking actors navigate ageing. Take Jack Nicholson, he says: “A lot of it has to do with his personality, but also he’s a good-looking gent, and so all of that is a power.” The same applies to women blessed with a game-changing force of beauty. “It’s very interesting watching good-looking women who grow older, and who don’t ever come to terms with the idea that the power they had as radiant young women has now moved into a new area, and they’re not going to stop the traffic just by being [beautiful]; that something else has to be a part of it.”

Then there’s Colin Farrell. “It’s really funny to see women’s reactions to him. They literally blush. He only has to walk in. It’s insane, but it’s a gift to the world, because he’s not a d***. He’s actually a really cool person underneath it all.

“People like Farrell and Nicholson are so great at what they do. They’re such brilliant actors. And then this other thing helps.” That grin again. “So if you haven’t got that, you just do the other bits.”

‘H is for Hawk’ is out in UK cinemas on Friday 23 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks