American Beauty’s midlife crisis: ‘The Kevin Spacey scandal doesn’t really have anything to do with the movie’

As ‘American Beauty’ approaches its 25th anniversary, Geoffrey Macnab looks back at the Oscar-winning film, and says, it should be judged on its own merits, not dismissed due to a string of sexual misconduct allegations against its star, Kevin Spacey

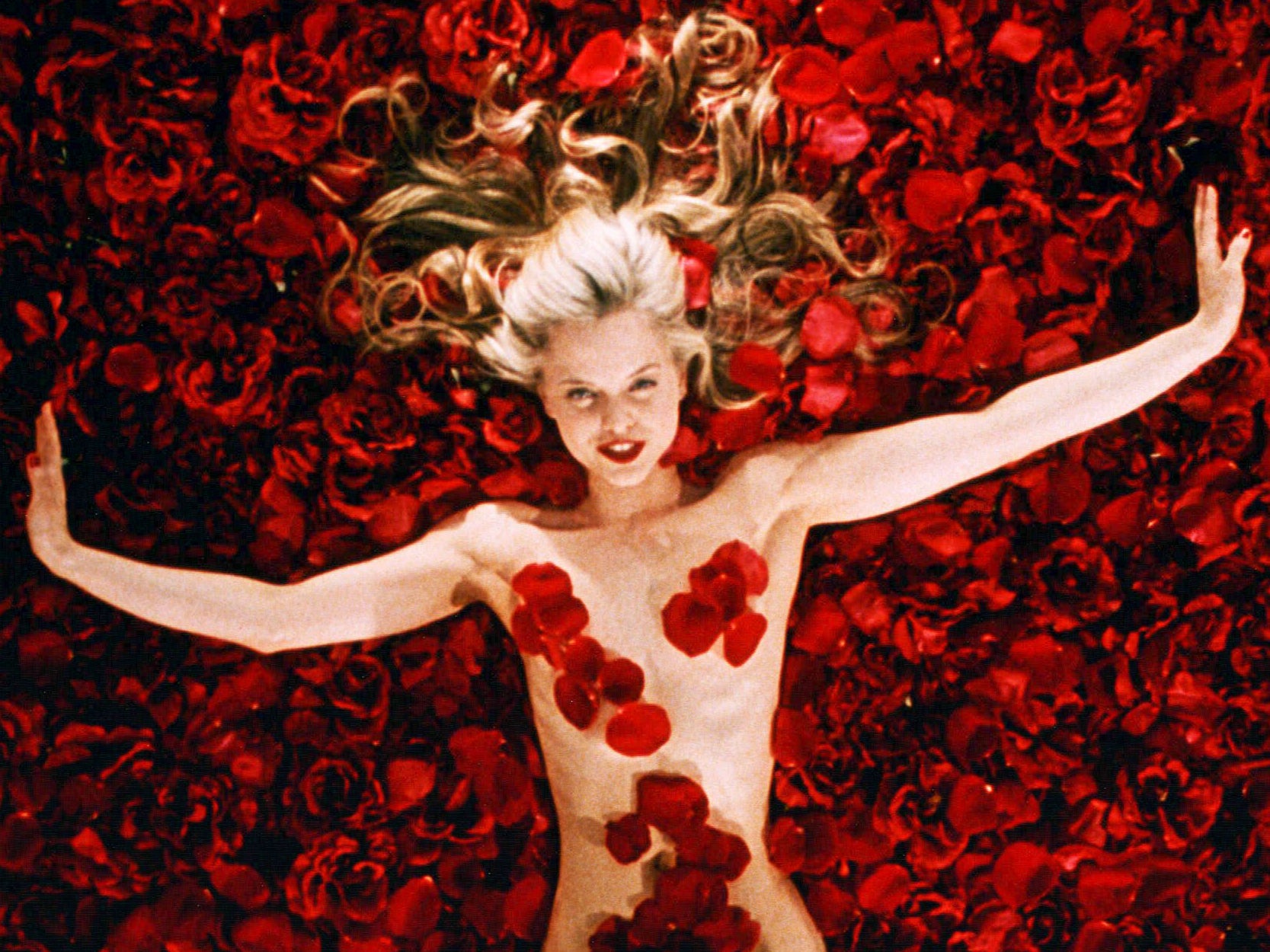

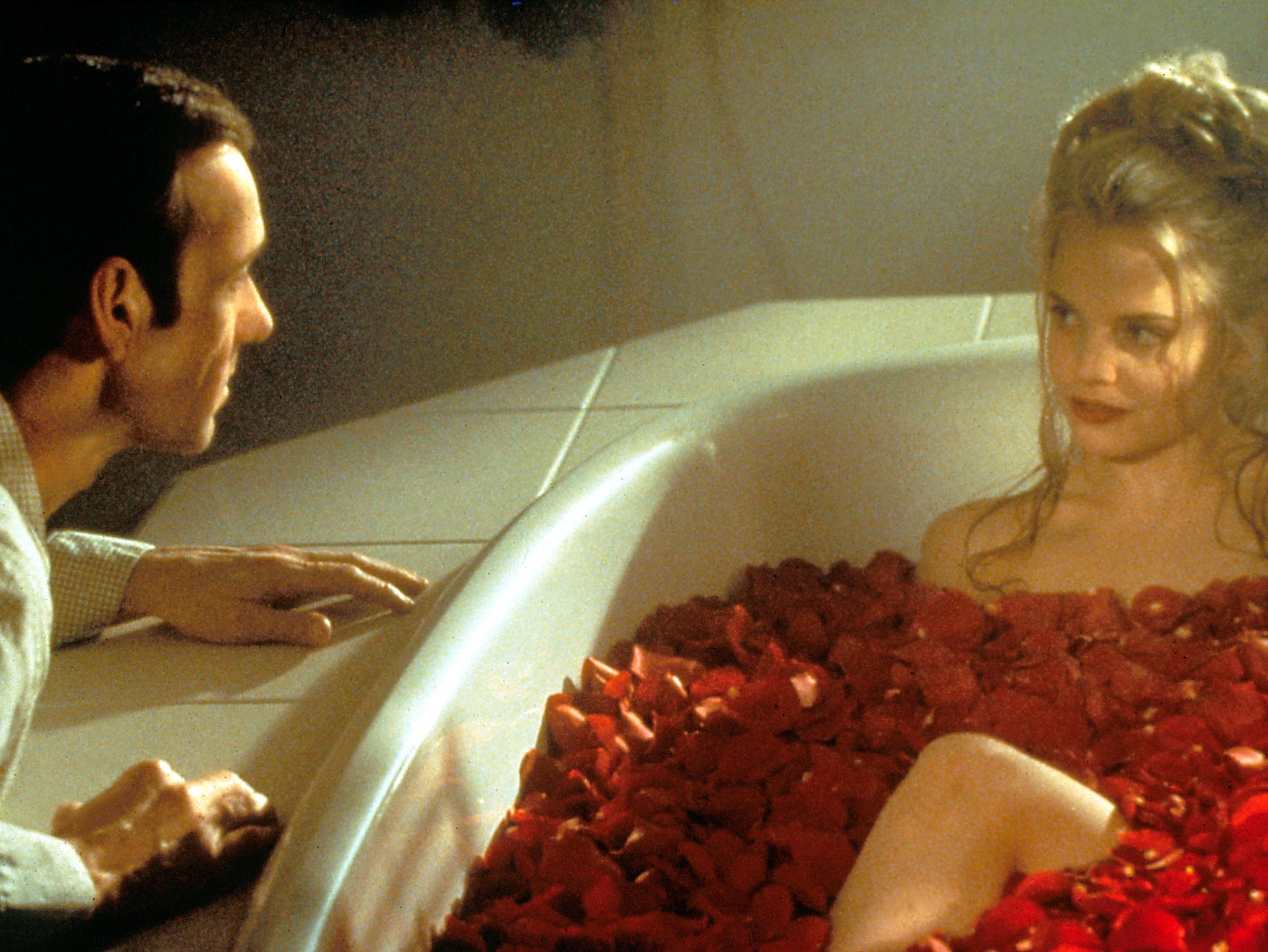

Moments after the opening credits, a middle-aged family man with a seemingly perfect life is shown jerking off during his morning shower – he confides in a voiceover that it’s “the highpoint of my day. It’s all downhill from here”. The movie is set in one of those American suburban neighbourhoods where everything seems idyllic, but it ends with him having his brains blown out by his neighbour. The 18-rated feature has teenage sex, adultery, drug use, lots of voyeurism and surrealistic scenes of a naked woman in a rose-petal-filled bath. There is a strange, somewhat random interlude in which two adolescents look in rapt wonder at camcorder footage of a plastic bag blowing in the wind as if it is the most remarkable thing they have ever seen.

Best Picture Oscar winners don’t come any stranger, queasier or more morbid than British director Sam Mendes’s debut feature, American Beauty (1999). It was a triumph at the time, picking up five Academy Awards, including Best Director and Best Actor for Kevin Spacey as the suburban dad Lester Burnham, who has a midlife crisis and becomes infatuated with his teenage daughter’s best friend. However, almost 25 years after the cameras started rolling in late 1998, it’s now a film that seems like very tainted goods.

Spacey has been in court in London this week as the defendant in a lurid sex assault trial in which he is accused of predatory behaviour toward a succession of young men. He denies all charges. His reputation has taken a severe battering in recent years and the film itself has suffered as a result.

Long before the actor’s fall from grace, several of his fellow actors in American Beauty experienced reversals and tough times in their careers. In 1999, Wes Bentley, Mena Suvari and Thora Birch, as the three young leads, all looked poised to become major stars. Bentley, who plays the peeping tom neighbour, Ricky Fitts, descended into drug addiction, although he has now rebuilt his career with his recurring role as Kevin Costner’s adopted son and potential nemesis in TV’s Yellowstone.

Suvari, cast as the teenage cheerleader, Angela Hayes, with whom Lester becomes obsessed, published a harrowing memoir, The Great Peace, in 2021, that chronicled her problems with addiction and the series of abusive relationships in which she had been trapped. Birch, playing Lester’s moody daughter, Jane, seemed almost as troubled off screen as on it – “she just stopped fitting in” TheGuardian wrote of her diminishing status within Hollywood and of how she began to be passed over for all the plum roles.

Discussion of American Beauty in recent years has hinged on what trade paper The Hollywood Reporter calls the question of “problematic faves”. How do fans deal with transgressions made by artists and filmmakers they once admired? It’s the same dilemma they face with Woody Allen and Roman Polanski movies – both directors have been mired in sexual misconduct scandals – or that older viewers are confronted with every time they watch a John Wayne western, given some of Wayne’s racist, homophobic pronouncements. Can they still cherish the work if those involved in making it have somehow sullied their reputations.

From today’s vantage point, the most surprising thing about American Beauty is how such a dark film achieved such mainstream appeal in the first place. Alan Ball’s intricately layered screenplay is trenchant in its depiction of the hypocrisy and monotony of middle-class suburban life. It suggests there is a huge and unbridgeable divide between generations – explored brilliantly in the fraught relationship between Spacey and Birch. Relationships between husbands and wives aren’t much healthier in the film. Lester and Carolyn (Annette Bening) are trapped in a sexless marriage and are thoroughly bored with one another.

Ball also offers a grim Darwinian view of the American workplace. Whether in magazine publishing – Lester’s profession from which he is threatened with redundancy – or real estate (Carolyn’s business), the white-collar executives smile grimly as they fight to cling on to jobs they hate anyway.

It takes very little to expose the flimsiness of the rosy life that Lester and his family appear to be leading. On one level, the moralising against the movie since the Spacey scandal broke is irrational. This was never meant to be a drama about wholesome, well-adjusted people. Lester spends a large part of the movie lusting over a teenage cheerleader who is the same age as his daughter. That seemed just as creepy in 1999 as it does now.

Billy Wilder was an obvious inspiration for Mendes and his team. As in Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), the film has a voiceover from beyond the grave with Lester telling his audience right at the start that “in less than a year, I will be dead”. Wilder films from The Major and the Minor (1942), Double Indemnity (1944) and The Lost Weekend (1945) to The Apartment (1960) also touched on adultery, murder, alcoholism and underage sex, but did so in such smart and witty fashion that viewers didn’t realise that the director was blithely breaking taboos.

At the time Mendes made American Beauty, he was a successful British theatre director with no first-hand knowledge of either the US studio system or of filmmaking in general. Like Wilder, he believes he benefitted from being an outsider in Hollywood. In a 2022 interview with the BBC, Mendes cited Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas (1984) as one of his key inspirations for American Beauty. Given that this is a road movie with very little dialogue and with large sections set in the desert, it seems an unlikely point of reference for a dark suburban satire. However, Mendes was drawing on the scenes in Wenders’s film showing characters “trapped behind glass”. The protagonists in his movie were likewise imprisoned in their work and family lives.

“Wim Wenders looked at America with the eyes of an outsider and so did Billy Wilder when he made Sunset Boulevard and so did Milos Forman when he made One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), and so did Ang Lee with The Ice Storm (1997),” said Mendes, observing how non-Americans are often far more perceptive about aspects of US life than those who have grown up in the country.

One key difference between American Beauty and the Wilder pictures lies in the casting. Spacey may have won the Oscar but he was very different from Jack Lemmon, William Holden, Ray Milland, Fred MacMurray, or the other likeable all-American types that Wilder generally put in his movies. By the late 1990s, thanks to films like Swimming with Sharks (1994) and The Usual Suspects (1995), Spacey was already well known for playing Machiavellians and bullies. On camera, long before his most famous role as the endlessly scheming politician Frank Underwood in Netflix series House of Cards, he invariably looked furtive, as if he was calculating the odds and plotting an advantage for himself. If a more open and spontaneous Lemmon-like actor had played Lester, the film might have had a very different tone.

Nonetheless, it’s a compelling portrait of suburban angst and despair. Spacey’s Lester is a complex figure, funny and defiant one moment and delusional, seedy, devious and pathetic the next. Dubbed a loser both at home and at work, he shares traits with other middle-class anti-heroes from 1990s cinema. In Joel Schumacher’s Falling Down, the Michael Douglas character’s life unravels in a similar way when he turns into a baseball bat-wielding vigilante. He too is a middle-aged, middle-class white man losing his footing in society. While Lester doesn’t attack anyone, he shares the same bewildered despair at the way his life is turning out. The violence here all comes from Chris Cooper as Lester’s sexually repressed military martinet neighbour.

Annette Bening has almost as much screen time as Spacey. She gives a deliberately theatrical performance as Lester’s wretchedly unhappy wife. The more miserable she grows, the more maniacally cheerful her behaviour becomes. Her bickering at the dinner table with Spacey’s Lester, as easy listening music plays in the background, rekindles memories of the most vicious moments between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. The film has one excruciating scene, in which husband and wife are on the verge of rekindling their sex life, when she suddenly realises that he might spill beer on their $4,000 couch “upholstered in Italian silk” – and the moment of passion is lost forever.

American Beauty wasn’t the only movie of the period prying into the darker side of American suburban family life. Todd Solondz’s wildly subversive comedy Happiness (1998) touched on paedophilia, rape, sexual abuse and murder, while trying to elicit laughs at the same time. Lee’s The Ice Storm had scenes of wife-swapping and substance abuse among its well-heeled middle-class protagonists.

Movies like these simply aren’t being made today – it’s one reason why American Beauty already seems like such a period piece. Big-name directors and stars have become very wary about dramas dealing with inappropriate or exploitative behaviour. It’s highly unlikely that anyone in the near future will win a Best Actor Oscar for playing a lecherous middle-aged white man trying to chivvy a teenage cheerleader into having sex with him.

“That’s why I loved playing Lester, because we got to see all of his worst qualities and we still grew to love him. This movie to me is all about how any single act from any single person put out of context is damnable,” Spacey told the audience in his Oscar acceptance speech.

Spacey’s words have a different resonance today than when they were first uttered on Oscar night all those years ago. Audiences are far less forgiving both of Lester’s worst qualities and of those levelled at the actor playing him. That doesn’t mean he gives a bad performance or that the film should be dismissed out of hand simply because he appears in it.

“Exhilaratingly intelligent” and “brilliantly staged” were among the verdicts from leading broadsheets when the film first appeared in cinemas. Other critics were equally enthusiastic. Hundreds put it in their top 10 for the year.

As more allegations emerge about Spacey as a “sexual bully” and predator, responses to American Beauty have inevitably changed. Given the ferocity of the backlash against the movie, which now features on lists of the “worst” and “most disliked” Oscar winners ever, you could be forgiven for thinking that all the original reviewers must have been in the grips of mass delusion.

However, they liked the movie for a reason. It was brilliantly shot by veteran cinematographer Conrad Hall, features a series of exceptional performances from its ensemble cast and ventured into murky, dangerous territory that contemporary filmmakers won’t go near.

Birch told The Hollywood Reporter in a 2019 interview, “it [the Spacey scandal] is traumatic. It hurts like hell [but] at the end of the day, that doesn’t really have anything to do with the movie or the script or the characters that we are playing or the experience that we had.”

It will take time, but Birch is confident that the “stain” left on the film will soon fade and that audiences and critics will again be able to judge American Beauty on its own merits – and not on the basis of its star’s already well-documented alleged misbehaviour.

‘American Beauty’ is available on Prime Video

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks