Lord of the Flies is a seismic, chilling masterpiece – of course, Adolescence creator Jack Thorne chose to adapt it

William Golding’s 1954 novel is required reading in schools across the world, and its title has become shorthand for the breakdown of civilisation, writes Martin Chilton. As a new TV adaptation arrives, it’s a reminder of how the book contains many warnings we must heed today

We can all be thankful that a young editor from Northern Ireland saved William Golding’s masterpiece, Lord of the Flies, from potential obscurity when he rescued the unknown author’s debut novel from a publisher’s “slush pile”. Charles Monteith took the time to read through Golding’s yellowing, stained manuscript – which bore the original title “Strangers from Within” – even though it had already been turned down by 21 publishers and dismissed by a previous Faber editor with the words, “absurd and uninteresting fantasy. Rubbish and dull. Pointless. Reject.”

Monteith asked Golding, then a 42-year-old English and philosophy teacher, to drop the first chapter, about an evacuation from nuclear war, and open with the moment where two schoolboys (Piggy and Ralph) meet on a desert island, after a plane crash has stranded a group of boys aged six to 13. Incidentally, Faber also ignored Golding’s other title suggestions, “A Cry of Children” or “Nightmare Island”, in favour of director Alan Pringle’s choice of Lord of the Flies, a key symbol in the book and the name by which Beelzebub is referenced in the Bible.

Lord of the Flies, which was published in September 1954, went on to sell more than 25 million copies worldwide. The title itself has become a cultural catchphrase, shorthand for the breakdown of civilisation and situations, from government rule to reality television squabbles, where factions descend into feral behaviour and lawlessness. Over the years, the novel has spawned numerous film adaptations and become required reading in schools and universities across the globe. And tonight, a new four-part BBC series created by Adolescence screenwriter Jack Thorne marks the first time the book has ever been brought to the small screen.

When Golding was handed the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983 by the King of Sweden, Carl XVI Gustaf told him: “It is a great pleasure to meet you, Mr Golding. I had to do Lord of the Flies at school.” The offhand royal snipe about Lord of the Flies being a book pupils “had to do” may resonate with millions of young readers who were force-fed the book as part of a school curriculum; however, it does not do justice to a seismic novel that has had a massive influence on popular culture. Ian McEwan said Lord of the Flies thrilled him “with all the power a fiction can have”, while Stephen King, in a foreword to a 2024 Faber edition, hailed it as a publication that simply “blew me away”. It was also a formative book for Thorne, who said he had read it with his mother as a boy, and that it “left a scar on me like no other”.

Cornwall-born Golding explained how the book had come about, recalling: “One day I was sitting one side of the fireplace, and my wife was sitting on the other, and I suddenly said to her, ‘Wouldn’t it be a good idea to write a story about some boys on an island, showing how they would really behave, being boys and not little saints as they usually are in children’s books.’” He succeeded. McEwan read the book at 13 at boarding school and was surprised to find that Golding “knew all about us”.

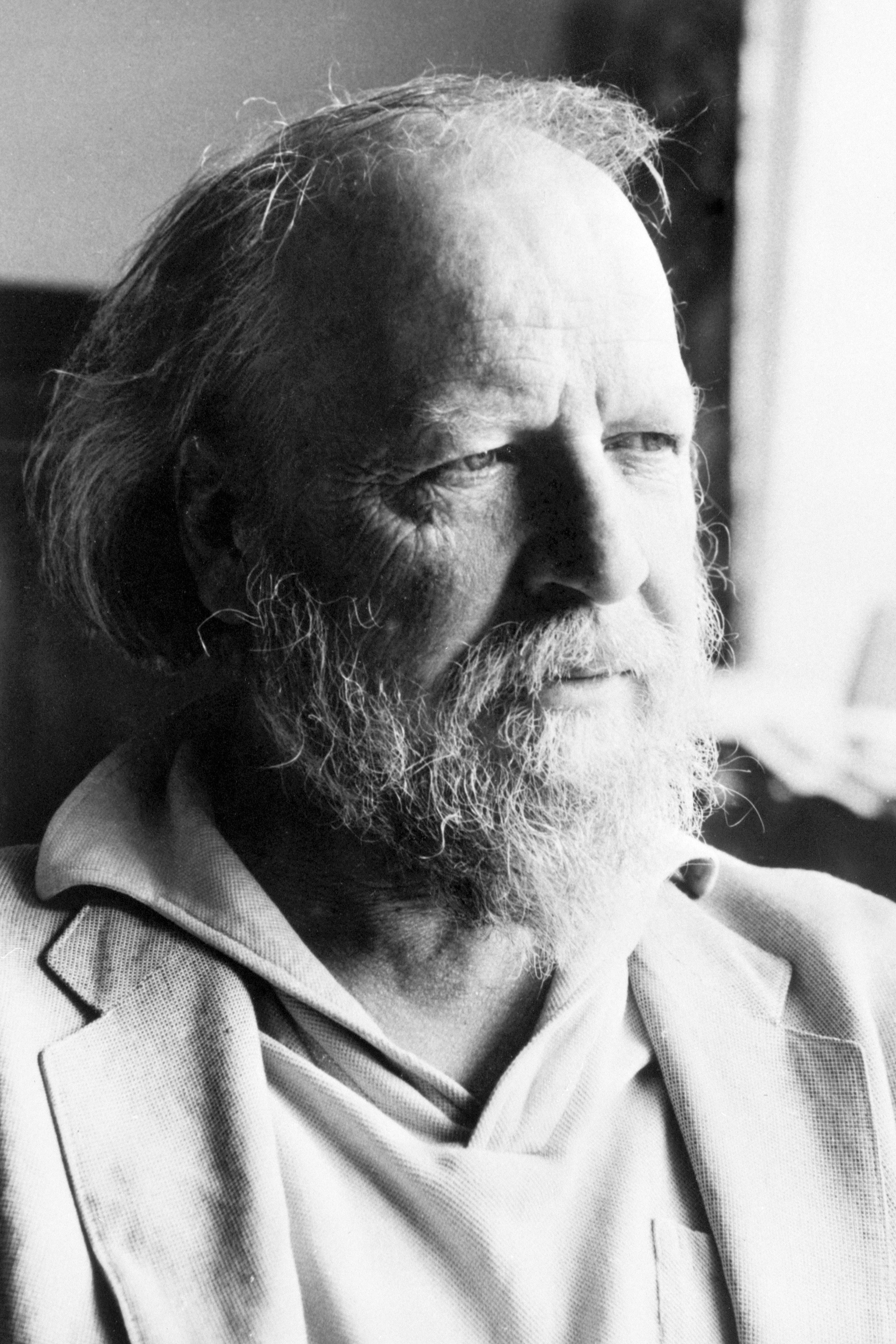

Golding’s starkly unsentimental view of boyhood was partly informed by his experiences as a teacher at Bishop Wordsworth’s School, a boys’ grammar school in Salisbury, a job he reluctantly plodded through to support his wife and two children. He was known as “Scruff” because of his unkempt jackets and scraggly beard.

In 2020, his daughter Judy Golding Carver gave a video interview in which she reminisced about her father, who died on 19 June 1993, at the age of 81. She said he liked children and wanted to understand them. One of the most fascinating anecdotes was about the day he took a class out to a Neolithic hill fort in Wiltshire. “He divided the class into two groups and told the groups to fight each other,” Judy explained: “Fairly soon, and I can’t imagine why he didn’t realise this would happen, he had to separate them because he was concerned that somebody might be killed. This was not good teaching, but on the other hand was probably helpful to his writing and he may be able to point to episodes in Lord of the Flies that reflect this.” Golding’s biographer John Carey wrote: “It occurred to more than one boy that Golding stirred up antagonism between them in order to observe their reactions.”

Lord of the Flies shows how a group of supposedly angelic British schoolboys (some are robed ex-choir boys) behave when cooperation unravels and groups splinter. Golding suggests the inevitability of violence when rules are abandoned. He referred tellingly to the boys stranded on the island without adult supervision as “scaled down society”.

Golding always said he preferred to be called a storyteller rather than a novelist and at the heart of his powerful story is the battle for ascendancy between 12-year-old Ralph, who embodies the values of civilisation, and Jack Merridew, who embraces savagery. Golding (whose father and brother were also teachers) knew all about the pecking order among children and how the world of school shapes boys. He explored how children suffer miserably when they are considered weak.

In Lord of the Flies, the most pitiful victim is the obese, asthmatic “fat boy” dubbed Piggy (we never find out his real name), whose nickname makes the other boys “shriek with laughter”. He is described as a dehumanised “bag of fat” by Golding, who shows how he “wilts” under the cruel abuse. The boys judge Piggy to be an outsider, not only because of his accent but because “he was fat and had ass-mar and specs”. Golding also turned his sharp eye on the tormentors, showing how with Piggy “once more the centre of social derision”, everyone else “felt cheerful and normal”.

As fear runs rampant over a supposed “beastie” stalking the island, the island paradise turns into a hellish place of suffering. Jack entraps followers who “understood only too well the liberation into savagery that the concealing paint brought”. With his followers steadily growing into a deadly “tribe” – Golding memorably describes them as “a solid mass of menace” – Jack boasts, “See? They do what I want.” Golding, along with most people in education, knew that bullying is not simply common in schools; it is the default relationship between young boys and teenagers. As Piggy’s fate demonstrates: you bullied or you were bullied. With no rules in place, a deadly price can be paid.

Simon, a small, shy boy, is the only one who understands that the “Beast” is a product of the other children’s imaginations. But he is murdered for explaining the truth. “There will always be people who see some things clearly and will not be listened to and will be killed for telling the truth,” Golding remarked, after the novel’s success. Perhaps his words ring uncomfortably close to the bone for some, especially the school board in North Carolina, who once tried to ban (or should that be rub-out?) his “demoralising book” because “it implies that man is little more than an animal”.

I was working within a class of GCSE state school students a few years back, when the English teacher asked the young teenage boys what they thought of their “set book”, Lord of the Flies. After the teacher batted away the inevitable artless request to supposedly find out what the word “bollocks” means (the only swear word in the book), the students were asked to raise a hand if they thought they were capable of descending into violence like the children in the story. Only two out of the 30 classmates admitted that possibility. Golding would probably not have been surprised at the lack of honest reflection – he remarked once that “anyone who believes he could not be a Nazi deludes himself”.

As well as Golding’s teaching career, the other formative influence on the book was global conflict. Golding served as a Royal Navy lieutenant during the Second World War, taking part in the D-Day landings. After witnessing atrocities, the book poured out of him, “like automatic writing”, recalled his daughter. He penned it in the Cold War-era, when the threat of atomic annihilation was a daily existential threat. Golding very deliberately examined the nature of humanity and societal breakdown using boys who are on the island in the first place because destructive adults have started a nuclear war.

Many decades on from the Cold War, Lord of the Flies has permeated popular culture to an unusual degree – as well as screen adaptations, it has inspired numerous shows, including a spoof sequence in The Simpsons – and indelible images, such as a severed, fly-infested head of a sow stuck on a pole, and the conch that Ralph blows on the beach, remain two of the most potent in literature.

King believes the book is “as exciting, relevant and thought-provoking now as it was when Golding published it in 1954”, while Thorne said his script for Adolescence was influenced by his work adapting Lord of the Flies at the same time. Thorne is also adamant Golding’s novel remains acutely relevant for our times. “We need to understand how we behave. We need to understand how others around us will behave,” he told The Big Issue. “This has a lot of parallels with where we find ourselves now. Golding was trying to examine that moment of horror and the savagery of the populism he saw – and there is no doubt we are under the shadow of populism again.”

Although the journey of the book is desolate and the ending bleaker still – when an emotionally cold naval officer who helps rescue the ragtag survivors learns of the killing of two children, he can only wish that a crying child will “pull himself together” – I can see why Golding believed the book showed he was an optimist, despite his “shock ending”. Despite its depiction of evil and its portrayal of people failing to live together harmoniously, Golding’s cold realism is tempered by the fact that the best of the children do try at democracy; Piggy and Simon do stand up to mistaken and disastrous authority. Ralph does try to keep society together.

Golding’s warning that “anything human will break given sufficient strain” deserves heeding in volatile times. The Lord of the Flies contains timeless and difficult truths and complexities for youngsters, even if it is probably best not to simplify it into a struggle between good and evil. Back in 1963, the acclaimed black-and-white 1963 movie version directed by Peter Brook disturbed audiences. I doubt Thorne’s mini-series will have the power to shock a generation used to television reports of gang killings and school massacres, and other events that routinely show how young people are capable of murdering each other.

Judy said that her father told her that the true subject of Lord of the Flies was “grief, grief, grief”, and it’s hard not to be moved by the fate of Simon, alone in the jungle, staring at the fly-blown sow’s head, its image imprinted on his brain. “The half-shut eyes were dim with the infinite cynicism of adult life,” Golding wrote. “They assured Simon that everything was a bad business.” Those words are as haunting in 2026 as they were when first published seven decades ago.

‘Lord of the Flies’ begins on BBC One tonight at 9pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks