Ian McEwan: ‘Too much talk about the news at supper rather ruins the fun’

The celebrated author takes a break from his Scottish holiday to speak with Claire Allfree about his new novel, the ‘alarming rate’ at which the world is rearming – and why, despite the apparent pessimism of his writing, he remains hopeful about the future

It feels fitting that my interview with Ian McEwan is delayed because of an electricity outage in the north of Scotland, where he’s on holiday. When the author does get Zoom up and running, the connection is a little unstable; he cuts a rather dim, indistinct figure, at times not entirely audible.

Set in the year 2119, McEwan’s new novel What We Can Know takes place in a waterlogged Britain, transformed into an archipelago partly by climate change. It’s easy to imagine its beleaguered inhabitants struggle with unreliable energy sources much more than we do. Yet despite its vision of a radically altered future, McEwan insists his novel isn’t a sci-fi one. “I have great respect for the sci-fi novel as a genre, but I’m not really interested in intergalactic warfare,” he says wryly. “Assuming we don’t have an all-out nuclear exchange and we just rub along from crisis to crisis, I was interested in what might survive in a rather degraded future.”

At the age of 77, McEwan has established a statesman-like position in British fiction, mapping out our national fears and anxieties across a 50-year career through novels such as 2019’s Machines Like Me, set in a world where artificial intelligence has already taken hold, and 2005’s Saturday, a response to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He is keen, though, that his latest book, in which the rising waters are also the result of a Russian nuclear attack several decades previously, is not considered a lecture on climate change. “You can’t write a novel about big generalisations,” he says.

All the same, What We Can Know undeniably reads as a strangely lovely lament for what has been lost, which, from the perspective of 100 years hence, includes the environmentally abundant world in which we currently live. “It’s a huge temptation for anyone who loves literature to wish you could still wander through Thomas Hardy’s Wessex,” says McEwan with a slight smile. “When I read Wordsworth, I can’t help but feel a great longing for the countryside we no longer have. So I’ve projected onto my narrator, Tom, some of my own nostalgia.”

What We Can Know is both an elegiac philosophical inquiry and a thumping literary mystery: Tom is a literary academic (yes, academics still exist in 2119) who, in what is surely the most whimsical premise of any speculative dystopia I’ve come across, becomes obsessed with a nature poem written by the long-dead poet Francis Blundy for his wife Vivien. The poem was revealed at a birthday dinner for Vivien in 2014, and almost instantly lost. Thanks to our contemporary insistence on recording almost every incidental and inconsequential detail of our daily existence, Tom finds enough information about Blundy on the Nigerian-controlled internet to deduce that the poem is likely buried by a barn in Gloucestershire. He sets out with his wife Rose, via boat, armed with a tent and a few tins of food, to find it.

The second part of the novel – much nastier, more brutal and more shocking than the first – is told from Vivien’s perspective, and upends everything Tom and the reader thought to be true. This classic McEwan narrative sleight-of-hand is partly a comment on the information age, in which a bounty of available data breeds false notions of intimacy and truth. “It’s certainly worth distinguishing between facts and knowledge by questioning the extent to which the internet gives us wisdom,” says McEwan, who has demonstrated his abiding interest in the borders between reality and its appearance in works as varied as his 2001 classic Atonement and the murky 1990 espionage thriller The Innocent.

More dramatically, What We Can Know is about environmental and intellectual decline. War and climate chaos have wiped out half of the world’s population; America has disintegrated into civil war; bandits roam parts of Britain; chocolate is a rare treat. Civilisation clings on in the UK, not least through its universities, but the humanities are in crisis and Tom’s students, whom he gamely attempts to engage in the literature of 1990 to 2030 – his specialist subject and a period that covers much of McEwan’s own career so far – aren’t too bothered about reading. Indeed, they don’t have much interest in the past at all.

McEwan describes his novel as “a mix of cataclysm, catastrophe, pessimism and a rather slender, nuanced hope”. In person, he definitely inclines towards the gloomy. There is an air of world-weary gravitas about him, and he talks slowly, in long, considered sentences. “We had some neighbours around for supper last night, and there was almost too much to talk about in the news,” he says. “It rather ruined the fun. What struck me was the way in which people are beginning to lose faith in the idea of the future. As we move further away from the Second World War, its influence on politics is fading, and you see the same mistakes being repeated by certain nation-states.” In regard to climate change, he adds, “I think there is a line that we are about to cross. And if you’ve lost faith in the idea of progress, then you really are plunging down a deep well.”

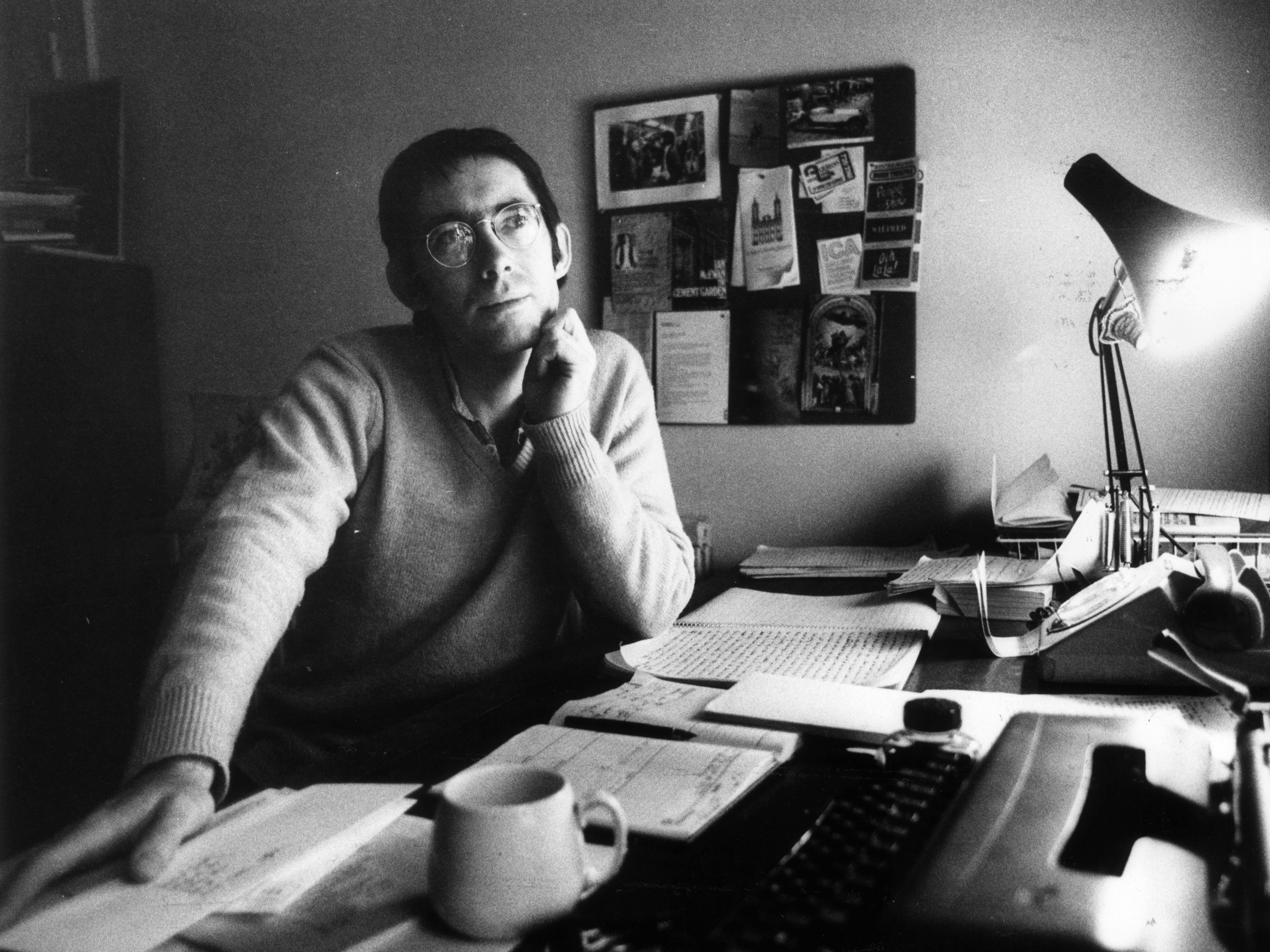

McEwan’s fiction has long been characterised by its mix of apprehension and jeopardy. Many of his early novels are built on sands of deep unease, be that in the macabre preoccupations of early works such as The Cement Garden and The Comfort of Strangers, with their storylines of incest, dismemberment and sadomasochistic fantasy, or the unforgettable set pieces found in Enduring Love or The Child in Time, in which a freak balloon accident or the sudden disappearance of a child upends normality in an instant.

Half a century into a writing career that began with the short story collection First Love, Last Rites, surely McEwan must feel that the world today, from the threat of climate change to the ascent of AI and the authoritarian ambitions of countries such as China, is teetering on a sharper knife-edge of crisis than ever before. Does he look back on those early gothic works, with their mix of domestic crisis and psychosexual foreboding, and wonder whether, on some level, he was anticipating our present moment?

“During the 1970s and 80s, the world always seemed threatened to me,” he says. “I was very much caught up in the protest against the United States and the Soviet Union possessing short-range nuclear weapons to enable them to fight a nuclear war by proxy in Europe. To me, that all felt very, very close. But then, when the Berlin Wall came down on 9 November 1989, and everything associated with the Cold War ended, I was absolutely joyous. I flew to Berlin on the 10th, and spent three days milling around [a period he describes in his loosely autobiographical 2022 novel Lessons].

I never realised how furious Angela Carter was about us male novelists until I read her biography

“But I think the precariousness of existence, and the way things can turn in a flash, is now our daily reality. The world is rearming at an amazing rate. And then there is the folly of those in charge, such as Trump and Putin. People worry their children and grandchildren are not going to have as good a life as they did.” In short, these fears have been manifest in his fiction all along. “So yes,” says McEwan. “I look back on those early novels and I think I was right.”

McEwan, who lives between London and the Cotswolds with his second wife, the writer and journalist Annalena McAfee, came of age as a writer in the Eighties. Along with Julian Barnes, Kazuo Ishiguro and his late great friend Martin Amis, he was part of a golden age of British fiction, during which authors swaggered around like rock stars, enjoyed stratospheric sales and advances, and opined regularly on TV. It was also very much a boys’ club. McEwan is far too varied a novelist to fall out of fashion (his oeuvre includes the mannered naturalism of Saturday and the conceptual playfulness of 2016’s Nutshell, which is narrated by a foetus), but the strident, machismo-charged novels of Amis, for instance, are now in some quarters being critically reappraised.

McEwan, who was last shortlisted for the Booker Prize nearly 20 years ago, for his 2007 novella On Chesil Beach (he’d won it previously in 1998 for Amsterdam), is sanguine about the evolution of literary taste. “I don’t think we will ever get back to a point at which all the creators of literature were rather stern men, and all the publishers were also rather dusty men, and all the writers occupying all the space and attention were all boys,” he says dryly. “Something weird would have to happen to get back to the jolly times of the mid-1970s. Jolly for us, at any rate.”

He’s aware of how those times come across today. He was perhaps less aware then. “I used to be the neighbour of Angela Carter, and we used to hang out together quite a lot,” he adds. “And I never realised, until I read a biography of her, how furious Angela was about us [white British male authors]. I thought she was riding this amazing crest as a writer. Yet she had a point, because right across all the literary pages of every newspaper, it was a man’s scene.” He wonders now whether this lack of gender parity took its toll on their friendship. “I think, because of this, our relationship faded away. I didn’t realise until I read this biography just how annoyed she was – and how annoyed I might have been if I’d been in her position.”

If you’ve lost faith in the idea of progress, then you really are plunging down a deep well

McEwan’s work abounds with sly metafictional tricks and narrative surprises that alert us to how the art form works while simultaneously seducing us with its power. What, then, does he feel about the threat AI poses to the novel itself? “AI ‘novelists’ don’t fall in love, or adore music, or mourn lost friends,” he says. “The software doesn’t have a body to inhabit, no tears or laughter. So it’s all twice-removed internet-scraped imitation.” He concedes this might in the short term be “commercially successful”, but he has no faith in the ability of AI to replicate a novel’s imaginative capacity. “I would expect, in the near future, mere plausibility – but no originality.”

McEwan is similarly untroubled by the so-called death of the novel – about which there has been chatter since the 1970s. “Since then it’s faced far stiffer opposition, the greatest perhaps being the rise of the long-form TV show,” he says, “but we haven’t in any other form, be it the movies or the theatre, bettered the representation of the subjective life, or of the individual’s relationship to their society, or our failures, or how it feels to fall in and out of love.”

“Anyway,” he adds, “every so often I find myself at a literary festival on a rainy Wednesday morning speaking to 1,500 people. This may be self-serving of me, but I’m pretty hopeful about all that.”

For all the apparent pessimism of his writing, McEwan holds a surprising amount of space for hope in general. Towards the end of What We Can Know, he quotes the economist Adam Smith: “There is a great deal of ruin in a nation”, meaning great damage is done to countries all the time that they somehow withstand. “All across the world, there are thousands of unrelated examples of rewilding or species rescue taking place that prove that the moment we stop doing something awful to a patch of sea or land, it pushes back much faster than anyone would have thought,” he says.

Moreover, he clings to his faith in human beings. “I know when it comes to us as a species, people worry about things such as attention spans, but attention spans are biological, and it would take about 10,000 years of evolution to really wipe them out,” he says. “And although things are bleak, it’s clear that it’s not too late to act. I try to hold on to the idea that it really does take a very long time to take the whole thing apart.”

‘What We Can Know’ by Ian McEwan is published by Jonathan Cape on 18 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks