Accidental brilliance or underhand machinations? How David Bowie’s legendary Glastonbury gig came to be

In this chapter from his new biography of the singer, Alexander Larman recounts the improbable events – including one subpar Bowie gig – that led to a history-making performance at Worthy Farm

When Bowie walked on stage at Worthy Farm in Somerset on 25 June 2000, received wisdom has it that the gig he performed over the following two hours was not just the highlight of that year’s Glastonbury Festival, but one of the greatest performances – if not the greatest performance – in the history of the festival. In terms of Bowie’s own career, it is commonly believed to be the single moment that he regained his crown as the reigning monarch of contemporary music, transforming him at a stroke from a figure whose best work was behind him to a peerless performer who inspired and impressed audiences, and artists, who were not even born when he began his career.

Many of those who were involved in the Glastonbury gig, whether as performers or organisers, have described it as their finest hour. Bowie’s keyboard player Mike Garson comments that “people still talk about it as the best show ever” while co-organiser Emily Eavis said, “I often get asked what the best set I’ve seen here at Glastonbury is, and Bowie’s 2000 performance is always one which I think of first.” Bowie’s PR Alan Edwards recalls that “David knew when he came off stage it had been a seismic moment. Everything changed from that day on.”

How he came to perform the iconic gig of the second half of his career is a fascinating story that combines high art, low chicanery, opportunism, luck and plain old- fashioned brilliance. As Edwards describes it, “I wouldn’t quite describe it as ‘underhand machination’: more like ‘accidental brilliance’.”

The year before, Michael Eavis came to see Bowie play London’s Astoria with an attitude of interest and expectation. This was soon dispelled by the set that Bowie played, which combined songs from Hours with more obscure tracks from earlier in his career, including “Cracked Actor” and “Repetition”. This did not necessarily suggest that Bowie was performing at the level of a Glastonbury headliner. As Edwards tactfully puts it, “my understanding was that Michael Eavis did indeed leave the Astoria gig half way through”. Bowie himself regarded the idea of headlining the festival as somewhat retrograde. “David also wasn’t in any great hurry to do a festival like Glastonbury,” explains Edwards.

Nonetheless, ever the publicist, Edwards idly trailed a story to The Sunday Times that suggested that Glastonbury would be interested in having Bowie perform. This is what public relations professionals call “a punt”, and what those not in that hallowed industry would describe as “a lie”. The headline simply said, “Bowie to Headline Glasto”. As Edwards observed, “the Glastonbury ticket office was inundated with ticket enquiries like never before in their history”.

The last time Bowie had played Glastonbury, there had been 2,000 festival-goers, most not unused to recreational drugs, and backstage catering was nothing more glamorous than Eavis’s kitchen, where performers were fed milk and eggs. This was an altogether different proposition. Edwards wrote in his memoir that, “after a few days, neither [my colleague] Julian Stockton or I had heard from David and we were worried that he was annoyed. Then we got a message from him: ‘You’re very naughty boys. Don’t ever do that again. Well done.’”

Bowie, who was anxiously awaiting the birth of his daughter Lexi with his wife Iman, had expected to play a three-hour, career-spanning set, but was peremptorily informed before the festival that this was impossible. “What crap news!” he wrote in a diary he was keeping for Time Out. “I had my production manager phone England yesterday to ascertain how late into the following morning we could play at Glastonbury, only to find that if I dare cross the curfew mark, the promoter will be fined £20,000 pounds a MINUTE... What a hopeless task.”

When Bowie arrived at the festival on 25 June to play the Pyramid Stage, he was atypically jittery. The audience was considerably younger than his usual fans, and the atmosphere on site was rowdy and undisciplined, not least because gatecrashers had swelled the permitted numbers of 100,000 to around 250,000. Bowie was playing after Travis and Chemical Brothers had headlined the previous nights, and he would be performing at the same time as the more upbeat act Basement Jaxx, who were headlining the Other Stage. He donned a remarkable outfit of Alexander McQueen frock coat and Oxford bags which was a conscious visual homage to his previous appearance.

Not that the vast majority of the audience cared: they wanted to be entertained, not edified. “It was magical,” recalls Garson, “but it could easily have gone wrong. When he walked out into the audience and saw a quarter of a million people, he got nervous. And he turned to me and said, ‘Go and warm up the audience.’ I walk out there and I’m thinking, ‘They don’t want to see me.’ And then here’s the wild thing. I sit down at the keyboard; no sound comes out. So there’s 100 engineers plugging things in. It turns out I had shut the volume off. So imagine if we went out with a band, and we sit down and there’s no piano. It would have ruined the whole show because you don’t start on the right foot.”

It was a surreal start but the next two hours saw Bowie at his artistic peak. At one point he forgot himself sufficiently to enthuse, “This is so cool for us, it really is cool. I f***ing love it!” It may have been a greatest hits set, but there were curveballs. Many of the best-known songs, such as “Let’s Dance”, were subtly rearranged, not to Bob Dylan levels of obscurity, but enough to keep the audience guessing as to what they were listening to before the inevitable, vast chorus exploded. Virtually every song was performed and sung about as well as they had ever been. Although Bowie himself, who was suffering from laryngitis, was initially unsure how well the gig had been received, he was soon reassured by the warmth of the reaction.

Afterwards, the columnist and noted Bowie fan Caitlin Moran wrote, ecstatically, in The Times that “you will never take David Bowie at Glastonbury, 2000, for granted again”. Moran’s final paragraph also observed: “O, my God, you will miss him, when he’s gone! You will miss him so much it will feel like half the lights go out, and never come back.” As word of mouth from the enthusiastic gig-goers spread, the performance came, rightly, to be venerated as that of an artist at the peak of his considerable powers.

Oh, how we would miss him when he was gone.

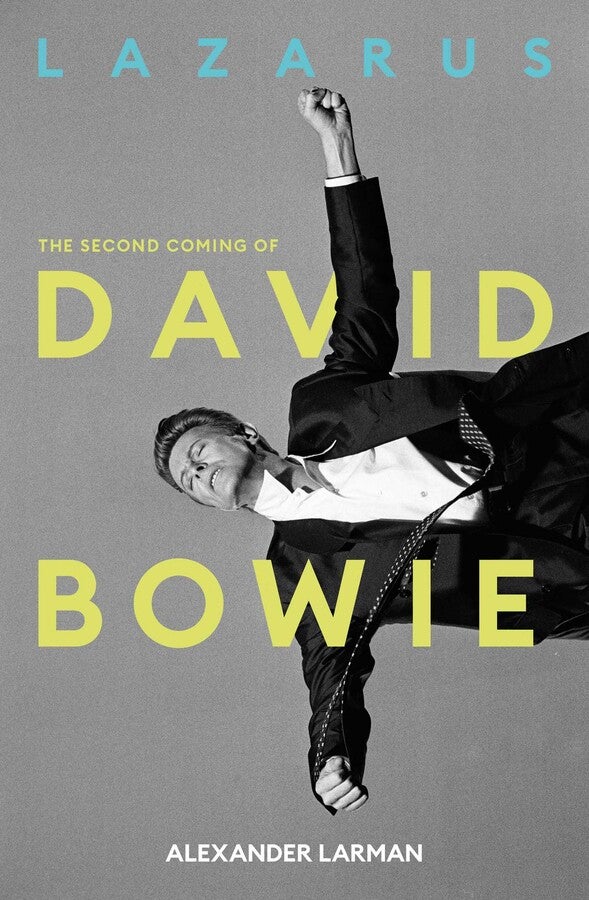

‘Lazarus: The Second Coming of David Bowie’ is out 1 January (New Modern) £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks