Carol Kirkwood and the BBC’s token woman problem

As a male interim BBC director-general is announced the same week that Carol Kirkwood unexpectedly steps down, former BBC producer and editor Fiona Chesterton looks at the snakes and ladders world of the BBC, and asks why women are still the losers

So here we are again, asking ourselves: does the BBC still have a problem with women, especially older ones? The unexpected departure of Carol Kirkwood from BBC Breakfast, although apparently her own decision to retire at the age of 63, is merely one pointer. The shocking facts just revealed in the report on diversity commissioned by the BBC itself are harder to brush aside.

The diversity review by former Bafta Chair, Anne Morrison, and former Ofcom exec Chris Banatvala, found “a noticeable mismatch” by the BBC in the treatment of older women on air. There were, they discovered, nearly four times as many male presenters over the age of 60 as female on screen. News division, it seems, lags some way behind entertainment.

You would think that the BBC would have wished to put well behind it the industrial tribunal case it lost to Miriam O’Reilly, who successfully claimed age discrimination after being dropped from the Countryfile line-up back in 2009. Apparently not.

When the BBC’s 17th male director-general, Tim Davie, resigned last November, I allowed myself to hope that the time might be right for the appointment – finally! – of the first woman to hold the top post in the BBC’s 103-year-old history.

Indeed, Davie has promoted several women to board-level positions and, outside, there are several potential female candidates with experience of the new world of streamers as well as of running media companies, here and abroad.

While I’m still harbouring the hope that the actual, rather than interim job – the most high-profile, high-risk and lowest-paid of media positions – might go to a woman, the announcement this week that Rhodri Talfan Davies will be acting as interim director-general, until a new, permanent one starts, has slightly dimmed that hope.

Who would have thought that a female Archbishop of Canterbury would be appointed – and on the throne – before a woman elevated to the top job at the BBC?

To understand why it’s taken the BBC so long, you should start by going back all of half a century, when a previous Labour government passed the Sex Discrimination Act into law. This was one of those landmark pieces of equality legislation designed to transform opportunities first for women and then ethnic minorities.

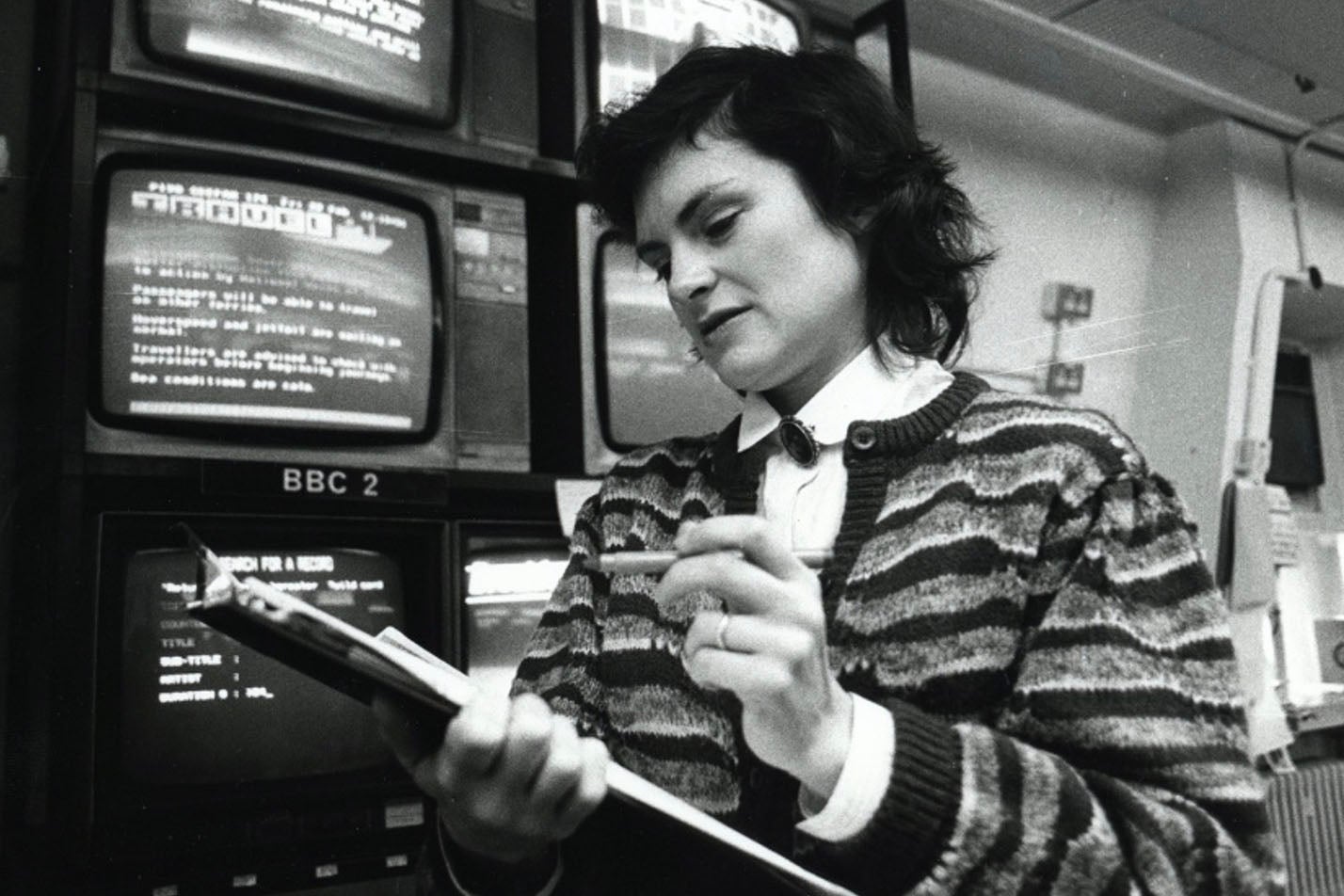

It came into force in December 1975, which was also the year I started at the BBC. I was the only woman working with seven men on the fast-track graduate news training scheme. All my tutors and supervising editors were also men – with one exception, the woman who taught us shorthand. And that was just how it was for a budding female journalist.

Two years before, in 1973, the BBC’s head of personnel produced a report for management on “limitations to the recruitment and advancement of women in the BBC” and quoted the views of the head of radio news. He thought that women could not do hard news as they “would be overcome with feeling if they had to announce, read, let alone cover any upsetting story”. Young women might have a tendency to giggle, reported another senior man, a third opined that middle-aged women might have ‘menopausal tension’.

That report, by outing such attitudes, helped encourage more progressive men as well as women to start making waves for change. It was not only women who were openly discriminated against. There was also, from my experience, a less recognised problem of class. The BBC’s graduate training schemes at that time traditionally drew recruits from a very narrow base, primarily public-schooled men from Oxbridge.

In newsrooms, more experienced journalists, nearly all men, were also recruited directly from Fleet Street. Some were non-graduates and from more modest backgrounds, but not in my experience with more modern attitudes to women. Management, however, was mainly the preserve of middle-class or even upper-middle-class men.

I noticed this, as I was brought up in a working-class part of Leicester and went to a state grammar school. My RP accent, derived from taking elocution lessons to correct a speech defect as a child, and honed, yes, at the University of Oxford, helped disguise my origins.

I encountered plenty of what we’d now call everyday sexism. Well, what counted as everyday then? The drinking culture, for example, was deeply embedded at the time and did not serve women well. In some newsrooms, when the men went to the pub at lunchtimes, women were expected to stay behind to mind the shop. A young woman wanting to be a BBC TV reporter at that time could be assessed in a meeting to consider her application, without shame, as having “great tits”.

And, until Kate Adie arrived in the 1970s, no women were working as news reporters and correspondents. There was an assumption that women were not cut out for international affairs, political or economic stories, nor for sports coverage. Angela Rippon was one of the first female newsreaders in the 1970s, but was expected to read what the male news duty editors wrote (the scripts all typed by women).

Routine sexual harassment, especially by middle-aged men in management as well as by several higher-profile presenters, of more junior and younger women, was brushed aside as something that women could just deal with. Many did. No one reported it.

Eventually, I had to go to the then separate department of current affairs, based in Lime Grove, to find a more conducive atmosphere than the various newsrooms where I did my training assignments. Yes, the drinking culture was still prevalent and yes, the management were still men of a certain class. But there were many more women in producer roles. Women like Barbara Maxwell, and her all-women team who ran Question Time, and Esther Rantzen, the queen of That’s Life.

In the freer air of Lime Grove, I made fast progress, rising from assistant producer to a senior producer role by the mid-1980s, but then found new barriers when I became a working mother. The BBC’s personnel department still had not worked out any clear policy towards women like me. I was one of the first women to negotiate to retain my staff job while working part-time, which, in 1985, was seen as an exceptional arrangement. If I hadn’t had the support of my male editor, I doubt I‘d have got anywhere.

I was one of the (anonymous) contributors to a report that year, which the governors commissioned from a recently retired controller of Radio 4, called Monica Sims. She had never married nor had children, but she was keen to improve the opportunities for working mothers like me to make progress into management. Her recommendations were wide-ranging, but she was no radical – in the face of considerable male opposition to what was termed “positive discrimination”, although all women like me wanted was the flexibility to keep working at jobs we loved and opportunities for promotion on fair terms – not special favours.

The Sims report unearthed some eye-opening statistics. They revealed for the first time how women in all departments were clustered into lower grades, mainly secretarial and clerical. Within TV, 88 per cent of women were in the two lowest bands, with just 13 women in the senior producer grade (of which I was one) and only one woman in management. In BBC Radio, there were just seven female senior producers, and zero in management.

But these two London-based divisions looked positively progressive compared to the nations and regions. This report showed that there was just one woman in a senior producer or manager role anywhere outside London in 1985 – at the very time when there was famously a woman in Downing Street.

Later in the 1980s, the BBC appointed its first equal opportunities officer, a woman called Cherry Ehrlich. She was keen that the focus shouldn’t just be on women producers and journalists but on encouraging women into technical roles, like camera operation, sound, studio direction, and engineering, which were seen as “men only” jobs at the time – while encouraging more men to become secretaries.

As for me, I had to leave the BBC in the early Nineties, to return to the BBC from Channel 4 later in a more senior role. I was collateral damage to the takeover of current affairs by news, and the closure of Lime Grove in the late 1980s. The last network programme I worked on in 1984, just before I took maternity leave, was axed. I was one of two daily editors on that last teatime BBC1 Current Affairs programme; the other was Tony Hall. Under the wing of John Birt, he went on to higher things as director of the newly-merged news and current affairs – and later became the 16th male DG. I, meanwhile, was offered a sideways, some would say downwards, move to regional news.

In the snakes and ladders world of the BBC, I may not have prospered. Still, other women made the breakthrough into top jobs in the Nineties and Noughties. Women like Patricia Hodgson, Dame Jenny Abramsky, Director of Radio, the late Jana Bennett, Director of TV, Lorraine Heggessey, Helen Boaden, Dame Liz Forgan, and Caroline Thomson all come to mind. But how come none of them got to be DG? Now they would be considered too old for the job, but I like to think that at least some of them had the wisdom not to go for this most thankless of public roles rather than simply being overlooked.

Even now, with a new generation of outstanding women on offer, I can still imagine the voices raised – behind closed doors, of course – arguing that the challenge for the BBC right now, called by some an existential crisis, needs a man. A strong man. ‘Sorry, but the time’s still not right for a woman at the helm. Of course, next time…’ they might say.

I hope I’m wrong.

Fiona Chesterton was a senior producer and commissioning editor at the BBC and Channel 4 and is a Fellow of the Royal Television Society for her services to broadcasting. Her memoir, ‘Not the Token Woman’, is published by Bite-Sized Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks