Is Bhutan’s tourism tax an elitist ruse or the blueprint for the future of sustainable travel?

As countries and cities across the world bring in entrance fees for travellers, Sean Sheehan considers whether Bhutan’s – the most expensive in the world – is worth it

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Touching down at Bhutan’s only international airport, which boasts one of the most difficult approaches in the world, is a heart-in-the-mouth experience. But it’s not the only explanation for visitors’ emotional responses to this tiny kingdom on the eastern edge of the Himalayas.

In the serene valley of Punakha, a dzong – a traditional fortress now serving as an administrative and religious centre – overlooks the confluence of two mountain rivers. Scarlet-clad teenage monks play elongated temple horns, a bodhi tree stands in the centre of the courtyard and inside the temple a Buddha gazes down as if he only has eyes for you.

The cultural appeal of the country – prayer flags, 4K colour and a deep spirituality – is bound up with its serious embrace of environmental stewardship. In another valley, Phobjikha, a favourite wintering place for the globally threatened black-necked crane, power lines were laid underground to minimise collisions, and every November a local festival celebrates the birds’ arrival from Tibet. And while potato farms surround the cranes’ marshy habitat, there are protections in place to prevent more land being drained for agricultural use. The cranes still can be observed at close quarters here and, whatever the season, the bowl-shaped valley is an unspoiled and uncrowded setting for hiking and communing with nature.

Tourism on a large scale would seriously threaten all of this. Such a concern is part of the thinking behind Bhutan’s Sustainable Development Fee (SDF). At $100 (£78) per day it’s the most expensive tourist tax in the world, and is a pure tax, paid up front, irrespective of accommodation, food, flights and other costs.

Bhutan is an expensive destination quite apart from the tax, with tourists having to shoulder the expense of travelling with a guide and driver (a service usually arranged via a tour agency, which also adds extra costs). This undoubtedly deters many from visiting – but if, like a safari or scuba diving holiday, Bhutan is regarded as a place reserved for the well-off, the imposition of an extra $100 a day is hardly something for the non-affluent to lose sleep over.

Read more on how Dubai is protecting its last patch of pristine desert

Accommodation in Phobjikha caters mainly to the moneyed traveller. There are three five-star hotels in the valley, two belonging to high-end brands (Six Senses and Aman) and one independent (Gangtey Lodge), all perfectly situated for heart-stirring views. They offer tempting experiences – meditation classes, candlelit, hot stone baths; superb restaurants – and the sort of personal service that you get at luxury hotels with as little as eight guest rooms. This all comes at a substantial price, around $1,000 for one night’s stay including meals but not activities (a hot stone bath and massage, for example, could set you back another couple of hundred dollars). There is alternative, more modestly priced accommodation in the valley, including small guesthouses and farmstays, and travellers will do their research to find a tour that suits their budget.

Such a range is true of many holiday destinations but it is writ large in Bhutan. Three-quarters of tourists to Bhutan are Indians, for whom the SDF is less than $15 a day. The different rate reflects both Bhutan’s crucial economic ties with India and the fact that, when it comes to other international visitors, this petite kingdom seems particularly keen to attract the well-heeled at the expense of less well-off travellers.

Bhutan’s focus on sustainability is yielding results – witness the nearly 40 per cent increase in its snow leopard population, from 96 to 134 individuals, since 2016 – and it is difficult to object to a tourist tax that is part of this policy. A country that has so far managed without traffic lights on its roads is negotiating a tricky way forward that acknowledges tourism as the second highest contributor to the national exchequer while mindful of the carbon footprint it leaves behind.

Bhutan’s pristine natural environment is vulnerable but so too is its remarkably cohesive culture. With neighbouring Tibet’s identity as an independent Buddhist state being systematically dismantled by the Chinese government, this culture is as precious a resource as the forests that cover 70 per cent of the kingdom. Jaded and world-weary traveller beware: you will find it difficult not to be moved by the contentedness of life here, where monasteries and Buddhist festivals are an integral part of the social fabric and graciousness informs every interaction.

Read more on the holiday swaps to avoid overtourism

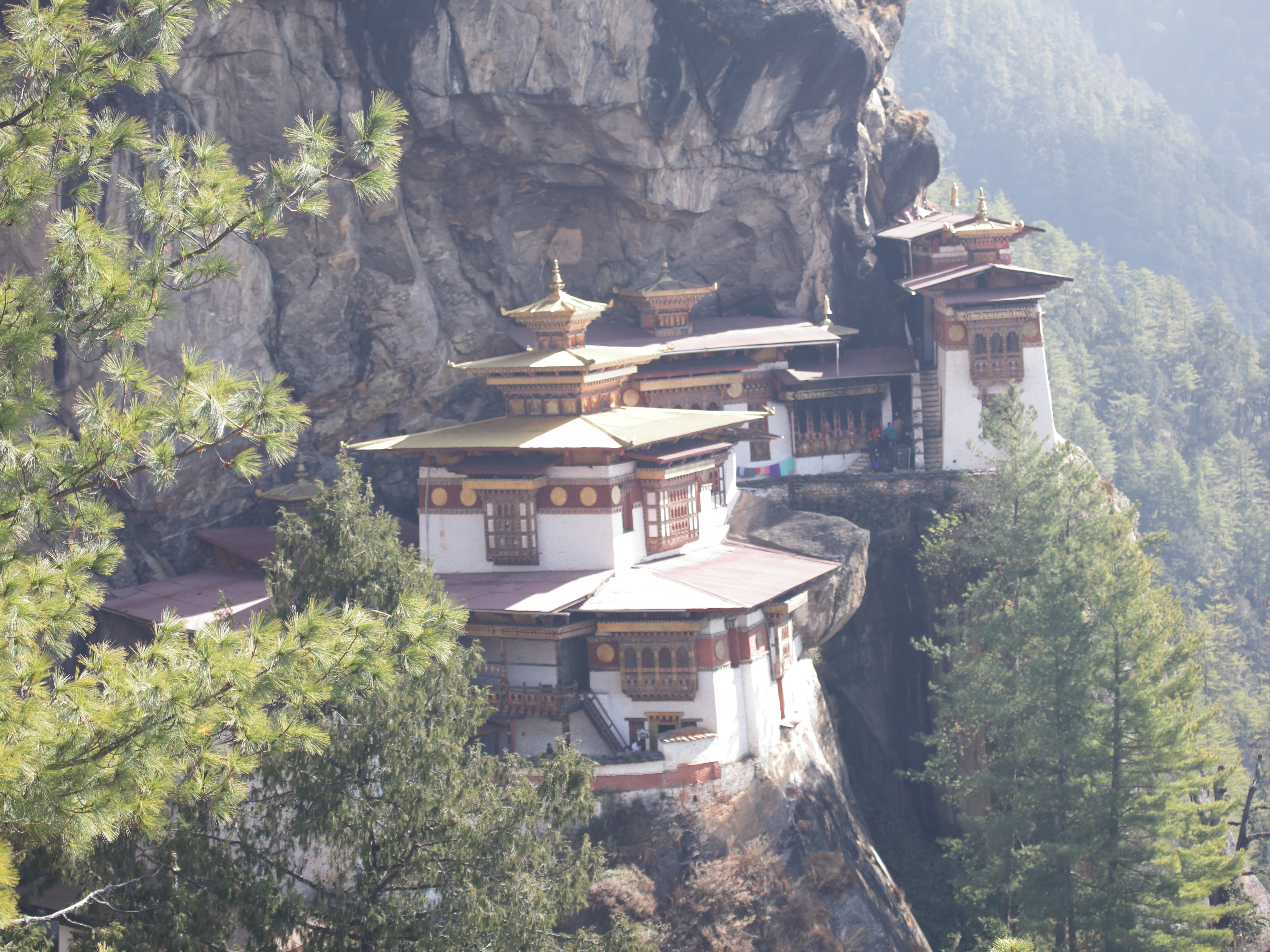

Bhutanese society is no Shangri-La. The winds of modernity are blowing in – smartphones are as common as prayer flags, and young people go to Australia to study and don’t always return – but the country still feels like a fragile bubble of pre-modernity in many respects. Rice paddies are farmed close to the centre of Paro (home to that terrifying airport approach) and the capital city of Thimphu is free of advertising billboards and buildings over five or six storeys. On a demanding trek up to Taktshang monastery, which clings precariously to a shelf of rock said to be the landing place of a mythical flying tigress, I met pilgrims from across Bhutan, some with children on their backs.

“If there is a hideout from karmic retribution, nowhere can we find it”, reads a saying of the Buddha inscribed at the National Museum of Bhutan. As the world hurtles towards ecological catastrophe, this feels terribly prescient. If $100 a day is the price to pay for one of the very few remaining hideouts we have, then maybe it is money well spent.

Travel essentials

How to get there

There are no direct flights to Bhutan from outside Asia. Multiple airlines offer daily flights from London to Delhi, in India (around nine hours), from where you can catch a flight with Drukair to Paro (around two hours).

Visas can be processed and SDF payments made online or through a tour agency.

How to get around

Paro-Thimphu-Punakha tours keep to the west of the country and could cost as little as £3,000 for two people in three-star accommodation (with too many buffets of fairly boring food); better hotels and experiences could easily double or treble that cost.

For superb trekking and more adventurous travel, head to eastern Bhutan; cultural, ecological, ornithological and sporting special interest trips are are well catered for. Bhutan Lost Kingdom Tours are highly professional and well able to curate a trip to suit personal preferences.

Read more on the rise of the eco-conscious sabbatical

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments